A safety probe into a Baltimore bridge collapse will include whether contaminated fuel played a role in a giant cargo ship losing power and crashing into the span, according to people familiar with the investigation.

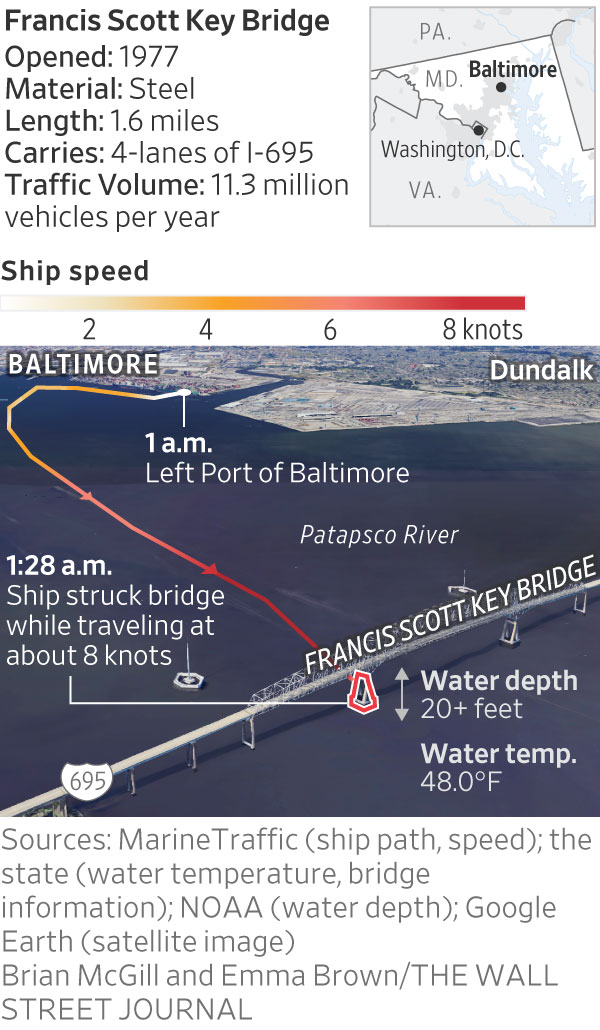

Safety investigators hadn’t boarded the ship, called the Dali, late Tuesday afternoon while it remained stuck at a pillar of the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge. The vessel could remain in that location for weeks. Rescue crews spent much of Tuesday searching for potential survivors.

The lights on the Dali began to flicker about an hour after the ship began its voyage early Tuesday. A harbor pilot and assistant reported power issues and a loss of propulsion before the crash, according to a Coast Guard briefing report viewed by The Wall Street Journal.

“The vessel went dead, no steering power and no electronics,” said an officer aboard the ship Tuesday. “One of the engines coughed and then stopped. The smell of burned fuel was everywhere in the engine room and it was pitch black.” The ship didn’t have time to drop anchors to stop drifting, the officer said. Crew members issued a mayday call before the accident.

Blackouts at sea aren’t common, but they do happen and have long been considered a major accident risk for ships.

One cause is contaminated fuel that can create problems with the ship’s main power generators, said Fotis Pagoulatos , a naval architect in Athens. A complete blackout could result in a ship losing propulsion, he said. Smaller generators can kick in but they can’t carry all the functions of the main ones and take time to fire up.

The investigation will include reviews of the vessel’s operations and safety record as well as those of its owner and operator, said Jennifer Homendy , chair of the National Transportation Safety Board, during a press conference. Crews will look at securing recorders, similar to a plane’s black box, from the vessel to better understand what happened.

The agency didn’t comment on what issues investigators have uncovered so far in connection with the incident.

“This is a team effort,” said Homendy. “There are a lot of entities right now in the command post.”

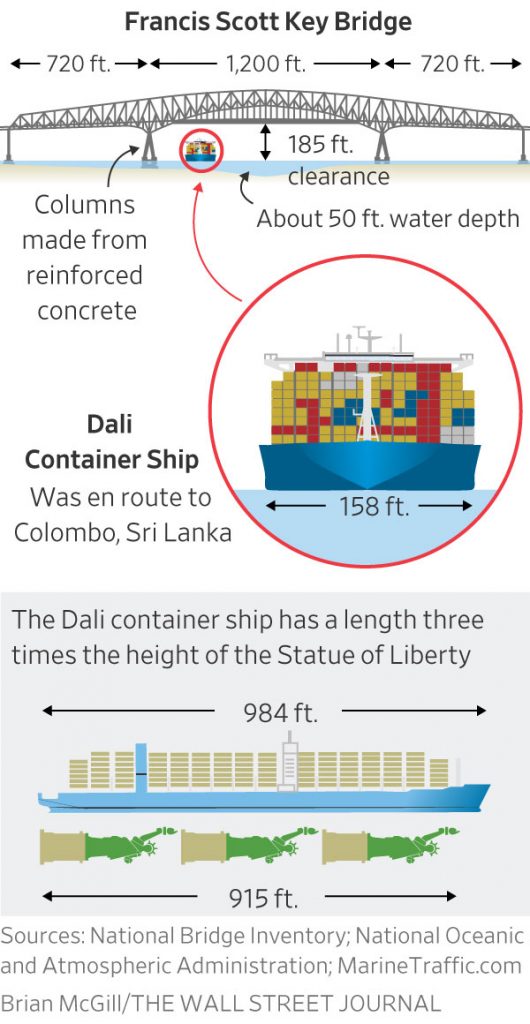

The Dali was built in 2015 by South Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries . The Panamax-type ship, which can carry up to 10,000 containers, is an industry workhorse and one of thousands that regularly transit through the Panama and Suez Canals. While dwarfed by the biggest containerships, a vessel the Dali’s size is typical for U.S. ports on the East Coast. A few days before entering Baltimore’s harbor, the ship had stopped in Norfolk, Va.

The ship has had more than 20 port state control inspections—reviews of foreign ships in national ports—since it was built, according to data from Equasis, an international shipping database. None of the listed inspections resulted in a detention, which could occur when a ship is deemed unfit to travel.

Deficiencies were noted in two such reviews: one done in Belgium in July 2016 that noted hull damage and another in Chile in June 2023 that reported an issue with the ship’s propulsion and auxiliary machinery, Equasis data show. The U.S. Coast Guard completed an examination of the vessel in September 2023 and didn’t identify any issues.

On the voyage Tuesday, Singapore-based Synergy Marine Group operated the vessel and it was hauling cargo for Danish shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk . The nearly 1,000-foot-long ship departed from a terminal at the Port of Baltimore and was heading to Sri Lanka. A Singaporean company, Grace Ocean Pte., owns the ship.

Two tugboats helped the ship steer out of the terminal Tuesday, but they pulled back early in the voyage, according to port officials. There were two pilots and 22 crew members from India aboard the vessel during the crash, said Darrell Wilson , a spokesman for Synergy Marine.

The ship was moving around 9.2 mph, according to authorities, which is typical for vessels traveling in the area. Ships as large as the Dali need to maintain a certain speed to avoid being pushed around by winds and currents.

The bridge collapse is set to lead to a multibillion-dollar string of insurance claims, covering everything from the loss of the structure itself to the disruption to businesses using the port, insurance analysts said. The Francis Scott Key Bridge was built in 1977 at a cost more than $60 million, which is around $300 million today when adjusted for inflation. Victims of the crash could also file claims against the ship operator.

The scale and complicated nature of the losses mean litigation is inevitable, analysts and academics said.

“You can write off the next 10 years in court actions,” said Robert Merkin , a law professor at the University of Reading.

Reinsurers, which take on risks sold to them by insurers, “will bear the bulk of the insured cost,” said Mathilde Jakobsen , a senior director at ratings firm AM Best.

The ship’s insurer, Britannia P&I Club, belongs to a group of specialized marine insurers that have reinsurance cover of up to $3.1 billion per vessel. Britannia said it is working to “help ensure that this situation is dealt with quickly and professionally.”

Claims on the ship’s coverage could be complicated by quirks in marine insurance law, such as a convention that limits liability based on the ship’s value.

One of the biggest claims in recent years was associated with the Costa Concordia, a cruise ship that sank near an Italian island in 2012. Thirty-two people died in the incident, and insurers paid more than $2 billion to claimants, according to London-based marine insurers. The 2022 fire and sinking of the car carrier, Felicity Ace, resulted in more than $500 million paid out under insurance policies.

A view of the Dali cargo vessel which crashed into the Francis Scott Key Bridge causing it to collapse in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S., March 26, 2024. REUTERS/Julia Nikhinson

-Jean Eaglesham contributed to this article.

Write to Costas Paris at costas.paris@wsj.com