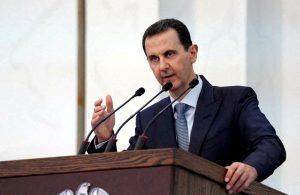

The fall of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad overturned the most profitable drug-smuggling network in the Middle East, exposing the former regime’s role in manufacturing and trafficking pills that fueled war and social crises across the region.

Captagon, a methamphetamine-like drug that has been produced for years in Syrian labs, helped the Assad regime amass huge wealth and offset the impact of punishing international sanctions, while also allowing allies such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia to profit from its trade.

Fighters affiliated with Syria’s “Hayat Tahrir al-Sham” (HTS) rebel-group display drugs previously seized at a checkpoint they control in Daret Ezza, in the western countryside of the northern Aleppo province, on April 10, 2022. A decade of appalling civil war has left Syria fragmented and in ruins but one thing crosses every frontline: the drug fenethylline, commercially known as captagon. The stimulant — once notorious for its association with Islamic State fighters — has spawned an illegal $10-billion industry that not only props up the pariah regime of President Bashar al-Assad, but many of his enemies. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP)

Days after they ousted Assad in a lightning offensive last week, rebels circulated videos from industrial-scale manufacturing and trafficking facilities inside government air bases and other sites affiliated with former top regime officials.

Among the locations where rebels discovered the alleged captagon factories and storage facilities were the Mazzeh air base in Damascus, a car-trading company in the Assad family’s hometown of Latakia and a former potato-chips factory in Douma near the capital believed to be affiliated with the ex-president’s brother. Footage by rebels and by journalists who filmed the sites at their invitation, including Reuters and Britain’s Channel 4 News, showed thousands of captagon pills hidden in fake fruit, ceramic mosaics and electrical equipment. They have said they destroyed at least some of the stored captagon.

Used by everyone from taxi drivers and students working late hours to militia fighters seeking courage, Syrian-produced captagon helped drive a demand for drugs across the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia, and became a source of international tension between Syria and its neighbors.

epa08520819 Members of the Naples branch of the Italian Guardia di Finanza (GdF) law enforcement agency inspect a world record seizure of a 14-ton haul of amphetamines, in the form of around 84 million tablets bearing the ‘captagon’ symbol and reportedly produced in war-torn Syria by the so-called Islamic State (IS or ISIS) militant group, hidden in three containers found in the port of Salerno, just south of Naples, southern Italy, 01 July 2020. According to the police, the value of the drug, which was found in three suspected containers containing paper cylinders for industrial use and machinery arriving at the port of Salerno, has been estimated at over one billion euro. EPA/CIRO FUSCO

The disclosures provide evidence of what had long been alleged: that the Assad regime was the driving force behind an estimated $10 billion annual global trade in captagon, which in recent years has become the drug of choice across the Middle East. Assad used the funds to sustain its rule and reward loyalists.

“This absolutely proves that the regime was systematically involved in captagon production and trafficking,” said Caroline Rose, an expert on the captagon trade at the New Lines Institute, a Washington think tank. “They were able to make these facilities as large as they wanted to, and plug and play.”

While captagon has long been known to have been produced in smaller labs across Syria—despite Syrian denials—the size and scale of the newly disclosed facilities show the staggering extent of the trade at every level of the regime.

“You can imagine the manpower, the resources that were required. It shows such investment into this illicit trade,” Rose said. “It penetrated so many elements of the regime: its political apparatus, patronage networks, the security apparatus.”

Pills, which, according to fighters loyal to the new ruling Syrian body, are captagon, are placed inside an apple-shaped container, on the outskirts of Damascus, Syria, December 12, 2024. REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir

Captagon was the brand name of a drug originally manufactured in Germany in the 1960s to treat conditions such as narcolepsy and attention-deficit disorder. After it was banned in most countries for being too addictive, criminal groups moved production of the drug to Lebanon and then to Syria after its civil war broke out in 2011. Most of the world’s captagon has been produced there in recent years.

Though gauging the size of illicit drug economies is inherently tricky, the New Lines Institute estimates the size of the annual captagon trade at about $10 billion—nearly the same as the European cocaine market—with the Assad regime taking in an estimated $2.5 billion.

The Syrian military’s elite Fourth Armored Division, commanded by the president’s brother Maher al-Assad, oversaw most of the captagon production and distribution, according to U.S., European and Arab officials. The U.S. Treasury in October sanctioned three people for involvement in the illegal production and trafficking of captagon to the benefit of the Assad regime. One of the sanctioned men owned a factory in Syria that allegedly served as a front company, sending pills worth over $1.5 billion to Europe concealed in industrial paper rolls.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the Islamist rebel group leading the blitz offensive that toppled Assad, has attacked the captagon trade as an example of the former regime’s moral and financial corruption. In a victory speech at Damascus’s Umayyad Mosque on Friday, HTS leader Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani said Assad had turned Syria into “the largest captagon factory in the world. Today, Syria is being cleansed, thanks to the grace of Almighty God.”

The dismantling of the Assad captagon empire will also strain the resources of Hezbollah, which according to U.S. and Arab security officials facilitated trafficking in areas under their control and secured the houses of drug dealers in southern Syria.

Economic activities in Syria such as taxation and smuggling, including of captagon, helped Hezbollah deflect the damage of international sanctions—which also affect its sponsor, Iran—and become more financially self-sustaining.

“Captagon allowed Hezbollah to diversify its source of revenue,” said Joseph Daher, visiting professor at the University of Lausanne and author of a book on the political economy of Hezbollah.

The size of Hezbollah’s profit from the captagon trade isn’t known, but the group is already under severe financial pressure after a devastating Israeli military campaign against its stronghold in south Lebanon that razed villages along the border to the ground. Israel’s military says its monthslong campaign since October last year killed about 3,500 Hezbollah operatives and injured twice that number to the extent that they are unable to fight.

Hezbollah, which is both a militia and a legal political party in Lebanon, draws much of its support from its ability to provide social services and welfare for its constituents, and is under pressure to compensate loyalists for property and relatives lost in the recent fighting.

“Hezbollah is most probably the biggest employer in Lebanon after the state,” said Daher, who estimated that the group pays direct wages and different forms of allowances to about 100,000 people, and provides various types of social services to several hundreds of thousands. “The various sources of revenues serve to maintain its hegemony over large sections of the country’s Shia population.”

Uprooting the captagon trade is unlikely to dent the growing appetite for drugs in the Middle East, experts say. The industrial-scale production in Syria amplified a demand for captagon since the late 2010s, which will remain high, Rose said.

If the blow to Syria’s captagon production leads to a permanent supply shortage, drug users will likely either pay more for captagon or turn to other and more dangerous stimulants that are surging in the region, such as crystal meth, she said.

Criminals in various layers of the chain might also simply move operations to other countries, particularly Iraq, which according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has emerged as a “critical conduit” for the captagon trade.

By the end of 2023, Iraqi authorities seized 30 times as much captagon as in 2019, with more than 4.1 tons of tablets confiscated in 2023 alone, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime said in a report earlier this year.

“Iraq is at risk of becoming an increasingly important node in the drug-trafficking ecosystem spanning the Near and Middle East,” the agency said.

Captagon has been smuggled via Jordan into the Gulf. It has also been sent via Lebanon into southern Europe, which has long been a transshipment hub for captagon destined for the Arabian Peninsula. Among large seizures in southern Europe, Italian police in 2020 confiscated $1 billion worth of captagon tablets. Dutch and German authorities have also busted captagon labs in their own countries.

“Ultimately, when we look at some of these criminal actors, they have already begun to diversify,” Rose said.

Write to Sune Engel Rasmussen at sune.rasmussen@wsj.com