Julie Marks rents out her Jericho, Vt., basement and a guest unit on Airbnb . When state officials proposed a bill in 2021 to restrict short-term rentals, she wrote an opinion piece against it in a local paper.

Soon, she got a message from Rent Responsibly, the national network for short-term rental host groups that is partly funded by Expedia Group , which owns the vacation rental-listing site Vrbo. Rent Responsibly encouraged her to form her own state group to oppose the bill.

“One night after a couple of glasses of wine at 1 a.m. I made a website and then boom—there it was,” Marks said. Within three weeks, 600 supporters had signed on.

At the suggestion of another state’s host group, she hired a lobbyist. Marks and other group leaders met lawmakers for coffee. They testified at hearings and hosted happy hours at local breweries. Within a few months, the Vermont bill was dead.

Airbnb hosts are emerging as a potent political force, often with the financial backing and organizational support of the industry that prefers to let the individual hosts be the face of the movement while the companies help behind the scenes.

Hosts have formed countless advocacy groups across the U.S. under Rent Responsibly. They are swarming statehouses, flooding towns with letters and showing up at community meetings by the hundreds.

And, in states such as Vermont, they are starting to tip the political balance of power.

“The professionalization of host advocacy efforts is really leading to a turning of the tides in a lot of communities,” said Noah Stewart, head of U.S. advocacy at Expedia Group.

Airbnb also helps leaders craft messages and keeps hosts in the loop about coming legislative hearings through its platform.

“That’s huge, because otherwise we have no way to reach all those folks,” Marks said.

Hosts’ rising political clout comes at a crucial time for the U.S. short-term rental industry, which is facing a wave of bills and rules designed to make it harder to turn homes into Airbnbs. New York City last year took the most aggressive step yet, eliminating nearly all short-term rentals when it began strictly enforcing registration rules . Other states and cities may follow suit.

“The snowball effect is the risk,” said Robert Mollins, a stock analyst at Gordon Haskett Research Advisors who tracks Airbnb and Expedia.

Hosts and short-term rental companies face a formidable coalition of hotel companies and unions and neighborhood groups worried about traffic and party houses. Housing advocates have also been critical, saying that renting homes on Airbnb shrinks the housing supply and raises rents.

Host groups say their industry promotes tourism, creating jobs and tax revenue, and helps middle-class homeowners pay their bills.

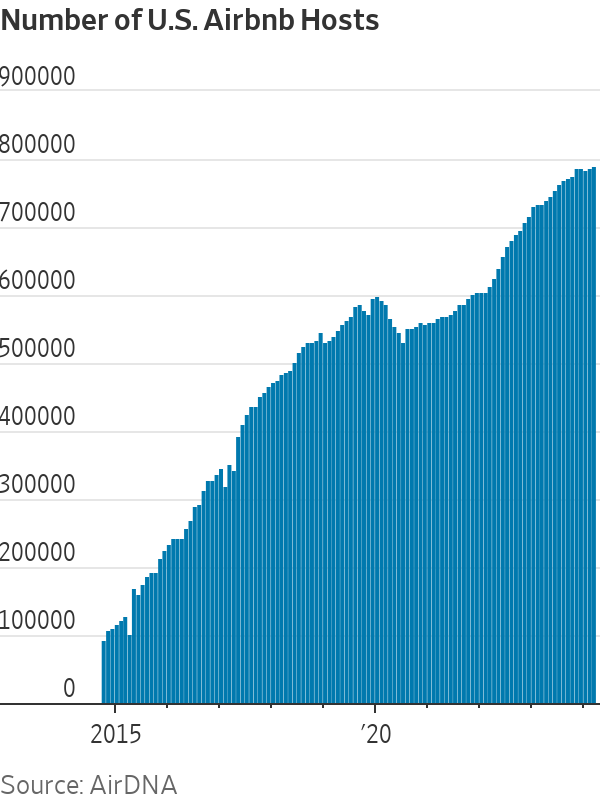

Upsurge in hosts

Until recently, hosts struggled to match the political clout of their opponents. One big reason that is starting to change: There are way more hosts now. Their number in the U.S. has grown to more than 790,000, according to data company AirDNA, an eightfold increase since 2014 and up 35% since the start of the pandemic.

Host revenues have also surged as Americans spend more on travel. That means there are now lots of people with lots more money to lose if Airbnb restrictions pass.

Colorado’s advocacy group, the Colorado Lodging and Resort Alliance, or Clara, launched in 2019. At first, members mainly used the host group to share information on bills. By 2023, the focus shifted to advocacy. Clara later used funding from the industry group Vacation Rental Management Association to hire its own lobbyist to help defeat proposed short-term rental regulations, said Toby Babich, a Clara founder.

The Colorado Senate introduced a bill this year that would quadruple property taxes on short-term rentals. But by then, “the wagons were circled,” Babich said. The group formed a coalition of stakeholder groups, held meetings with lawmakers and solicited economic impact studies.

In April, the bill died in committee.

Not all groups have been successful. Surging rents during the pandemic led to more calls to restrict short-term rentals, which can shrink the housing supply as homes get turned into de facto hotels.

In Hawaii, short-term rental owners last year formed a statewide group and lawmakers later introduced a bill that would leave counties free to set limits on Airbnbs. Hawaii has faced surging rents and the Lahaina fires , which destroyed hundreds of homes on Maui, worsened the matter.

“The fires provided a lot more fuel for this fight,” said Jennifer Wilkinson, vice president of the state host group Hawai’i Mid and Short-Term Rental Alliance. The bill became law in May, and the mayor of Maui has proposed a county law that would remove thousands of short-term rental listings on the island.

In New York, hosts last year staged protests outside city hall and filed a lawsuit alongside Airbnb, but failed to stop the de facto short-term-rental ban .

Help from Airbnb

Aside from independent, politically active host groups such as Clara, there are also more informal groups set up by Airbnb. Andrea Henderson, a short-term rental host in Denver, received an Airbnb email soliciting applications to be a host “community leader” and run one of these groups. She was selected in 2022.

She isn’t on the company’s payroll, but said she does get funding to put on local meetups. The Denver group grew from 10 members in 2022 to more than 1,000 in 2024, she said.

Many hosts hadn’t heard of the Colorado Senate bill. Henderson corresponded with a member of Airbnb’s advocacy team, shared information about the legislation with hosts and encouraged those interested to testify at hearings.

Some independent groups also get support from Airbnb and Expedia. “They speak authentically because they’re not hired consultants, they’re not PR agencies,” said Jay Carney, global head of policy and communications at Airbnb.

In Pennsylvania, the Poconos Association of Vacation Rental Owners has biweekly calls with members of the two companies’ policy teams who help draft letters to homeowners associations and community boards, said the group’s executive director Ricky Cortez.

Still, for the most part the companies stay in the background, and hosts say they are happy with that.

“If Airbnb walks in the door, no one is going to support them,” Marks said. “But if Julie Marks and her three friends, who are also Vermonters, walk through the door, they’ll listen.”

Write to Konrad Putzier at konrad.putzier@wsj.com and Allison Pohle at allison.pohle@wsj.com