FLORENCE, Italy—The city of Botticelli’s “Venus” and Michelangelo’s “David” is now the city of Airbnb.

The spread of short-term rentals has pushed up rents and priced out residents. Shops that once served locals have become rarities. Lockboxes for keys sit next to the doorbells at many buildings’ entrances.

On some streets in central Florence, most of the buildings have at least one lockbox, which allows visitors to access their short-term apartment without having to meet the owner. Some buildings have four or five.

The telltale lockboxes have also proliferated along the canals of Venice, the small alleys of the Cinque Terre and the chaotic streets of Rome.

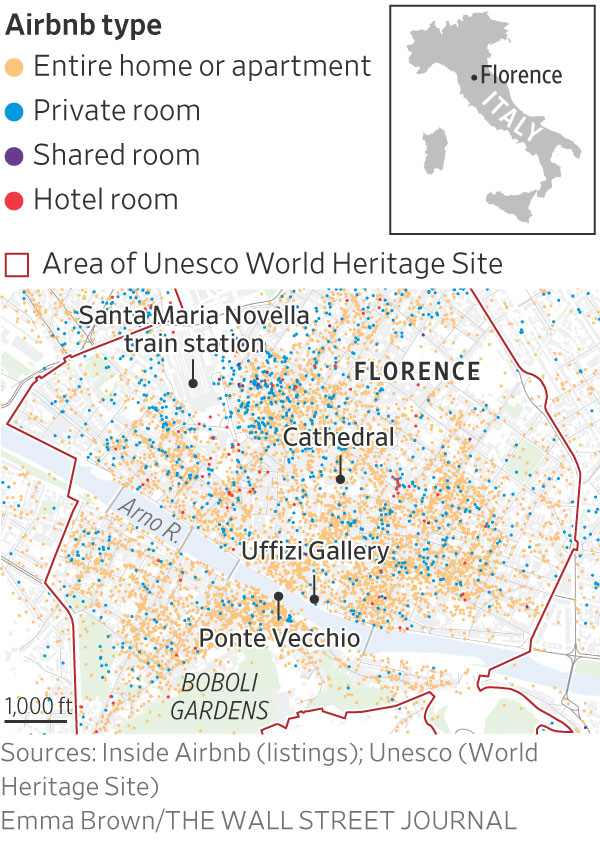

As Airbnb has moved in, residents have moved out. Almost 30% of homes in central Florence are listed on Airbnb, according to a study by two professors at Rome’s La Sapienza University. That doesn’t include the apartments listed on other platforms such as Vrbo.

Florence’s historic center—a Unesco World Heritage site—has more beds listed on Airbnb than it has residents, according to the study. “Even if you have a lot of money, you can’t find a place to rent in Florence because all the apartments are on Airbnb,” said Linda Sanesi, who lives outside the city’s central area and runs a hair salon with her husband on a small street next to Florence’s cathedral.

Up until the 1990s, stores serving locals populated the downtown area. Few have survived. About 60% of Sanesi’s clients are tourists looking for a haircut.

Airbnb is aware of the problems and pressures that large numbers of tourists can create in historic cities such as Florence, a spokesman for Airbnb said.

Italy has mostly allowed short-term rental sites to operate without regulation. The result has been an explosion of listings.

Airbnb listings in Florence have more than doubled since 2016. Long-term rents have risen by 42% in that time, according to Mayor Dario Nardella. Three-quarters of the short-term rentals in Florence are in its historic center.

The 40,000 residents who remain in central Florence “have suddenly found themselves living in condominium-hotels with costs that have increased by up to 30%, dirty sheets everywhere, noise, intercom calls at all hours from tourists asking residents for assistance as if they were hotel staff,” Nardella said.

“If you’re the only resident in a building and the other seven apartments are on Airbnb, you resist for a while—then you leave,” said Massimo Torelli, a Florence native and a member of a left-wing association that fights for affordable housing for residents. “How long are you going to endure people coming and going at all hours, partying, all the stuff we do when we’re on vacation? It’s normal, but do you want to live there? Venice has been lost, but we can still save Florence.”

Massimo Torelli advocates for affordable housing in Florence. PHOTO: ERIC SYLVERS/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The squeeze on affordable housing won attention in Italy this year after students began camping out in front of universities in Milan, Rome and other cities to protest the high rents.

Property owners in Italy often prefer to offer their apartments on Airbnb than to find a long-term tenant. It can be not only more profitable but also less risky. Italian law makes it difficult to evict long-term tenants who don’t pay the rent they owe. If the tenants have children living with them, it is almost impossible.

Residents of Florence, however, have had enough of Airbnb. In October, the city passed a law banning new listings on Airbnb in the historic center. Properties that already offered short-term rentals can continue. The city hopes to be a trailblazer in Italy, showing that the spread of Airbnb can be stopped.

“We’re trying to break through the country’s inertia,” Nardella said. He said that he has done all he can as mayor, given municipalities’ limited powers and that Italy needs a national law regulating short-term rentals. “I’m convinced that if we take the first step, others will follow.”

The Airbnb spokesman said the company “recognizes the challenges facing historical cities and welcomes progress from the Italian government on new national rules, which will help support the policy goals of cities like Florence.”

Florentine property owners and professional managers of short-term rentals are promising to fight the city’s restrictions in court.

Italy’s government has debated what to do about short-term rentals, but has yet to make any significant intervention. Its draft budget for 2024 would raise the tax rate on rental profits to 26% from 21%, starting with the second apartment an owner rents out. The first rental would still be taxed at 21%. Critics say it will make little difference.

Other European tourist destinations have restricted short-term rentals. Amsterdam introduced its first regulations in 2014, under which apartments generally can’t be rented out on platforms such as Airbnb for more than 30 days a year. Owners can rent out only one property, and a permit is needed for offering an entire apartment. Barcelona, Paris and Berlin have also aggressively reined in short-term rentals.

New York City began enforcing new rules in September that Airbnb called “a de facto ban on short-term rentals.” Hosts must register with the city, can’t rent out an entire property and must be present when they have paying guests.

Critics say Florence’s ban on new offerings doesn’t go far enough.

“Freezing the situation doesn’t resolve the existing problems,” said Filippo Celata, one of the authors of the Sapienza University study. “Cities such as Amsterdam that moved several years ago have managed to control the growth of short-term rentals. It might be too late for cities that move now.”

Write to Eric Sylvers at eric.sylvers@wsj.com