Three centuries ago, London lawyer James Puckle dreamed up a gun he hoped would be a hit with the British Navy, and a financial boon for himself.

Instead, Puckle’s peculiar creation, resembling a giant revolver on a tripod, flopped spectacularly.

Only a handful were ever made, and Puckle and his gun were relegated to mere footnotes in weapon history. One might say his invention went out more with a whimper than a bang.

But now, thanks to the strange twists and turns of America’s endless gun debate, Puckle and his gun are having a moment. The Puckle gun has peppered legal briefs, orders, and testimony in gun-related court battles across the country including cases in California, Oregon, Virginia, and Louisiana, according to Wesleyan University’s Center for the Study of Guns & Society.

What the Puckle is going on?

Pucklemania really began firing on all cylinders around 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. vs. Bruen. That decision overturned as unconstitutional New York state’s restrictions on who is allowed to carry a concealed gun. Justice Clarence Thomas , writing for the majority, declared gun laws must be “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

Some interpreted that to mean that laws about modern firearms needed to find analogous firearms laws from when the Second Amendment was developed.

‘The phone starts ringing’

Suddenly, lawyers on both sides of current court fights went down ye very olde gun rabbit hole. If rapid-fire guns like the Puckle contraption were well known when the Founding Fathers were writing gun laws, that could have a bearing on laws for modern rapid-fire guns.

Firearm historians—accustomed to toiling in obscurity—now find themselves in hot demand as expert witnesses.

After Bruen, “The phone starts ringing and I get really busy,” recalls Clayton Cramer, an Idaho-based gun historian who has provided expert testimony for gun-rights groups.

Cramer has long professionally opined on gun laws and antique guns, but he’s never made more money at it than in recent years. Historians aren’t only riding the Puckle wave, but they are being sought after to weigh in on, say, the pepper-box revolver or the air rifle carried on the Lewis and Clark expedition.

But “the Puckle gun gets all the attention,” says Cramer. “Puckle. It just sounds funny.”

Not surprisingly, experts are trading verbal shots over the Puckle’s significance.

Cramer hailed Puckle’s gun as “a wonder weapon” in one court document. He believes it highlights a long history of inventors trying to develop rapid-fire weapons.

‘Bizarre showpiece’

But Brian DeLay, a University of California, Berkeley history professor and expert witness for those advocating stricter gun laws, takes a different view. He dismisses Puckle as a con man and his gun as “little more than a bizarre showpiece.” In one legal filing, DeLay called the Puckle gun an “interesting, flawed design” that “sunk into deserved obscurity.”

It is a wild turn for a once-forgotten invention mostly known in its day—if known at all—as a disappointing novelty.

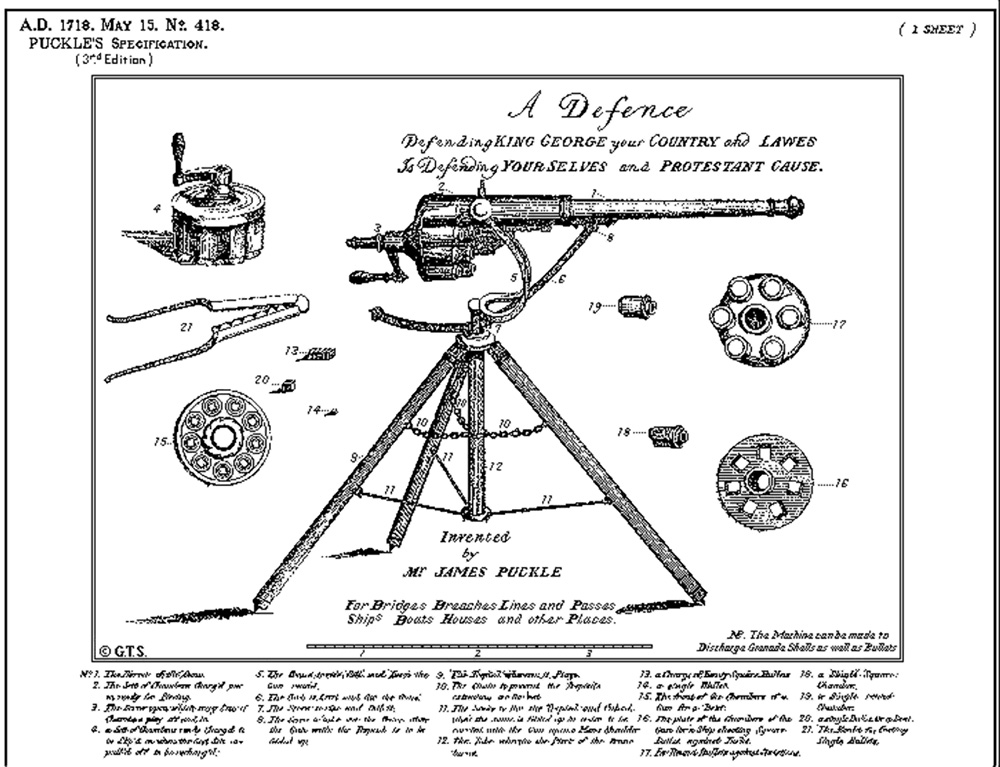

In 1718, Puckle filed a patent for “A Portable Gun or Machine called a Defence, thatt Discharges soe often and soe many Bulletts.”

The expensive, brass weapon sat on a tripod and required a trained crew to operate a cylinder for firing and loading lead rounds. The patent described one cylinder holding six-round bullets, for firing at Christian enemies, and another cylinder, with seven square bullets, for Muslim enemies, ostensibly to inflict more harm.

That bullet configuration “even by 18th century standards screams whackjob,” says Jonathan Ferguson, keeper of firearms & artillery at the United Kingdom’s National Firearms Centre.

The British military punted on using the Puckle weapon, deeming it clumsy and unreliable. Undeterred, Puckle sought investors. In a demonstration, his crews fired 63 rounds from the gun in seven minutes—fast for the time.

The public reaction? Meh. Londoners silly enough to invest in “Puckle’s machine” found themselves mocked in verse on playing cards:

“…Fear not, my friends, this terrible machine,

They’re only wounded that have shares therein.”

Puckle’s sole customer appears to have been the Duke of Montagu, who purchased two for a Caribbean expedition.

Puckle died shortly after his gun flopped, in 1724. He was buried in a London churchyard later obliterated by bombs in World War II.

Ferguson, at the National Firearms Centre, places Puckle in a tradition of “wacky gentlemen inventors” and tinkerers whose creations were “widely expensive and not that widely known.”

‘Shocked, but delighted’

Meanwhile, the exact number of Puckle’s devices in existence remains a mystery. A current duke possesses two. Another might lurk in China somewhere, according to Ferguson.

Joe McClain, a retired historic-weapons curator in Florida, spent years successfully convincing a Belgian collector to sell him one. (McClain, who has researched and written about Puckle, believes Puckle didn’t invent the gun, but stole the idea or had someone else make it for him.)

Robert J. Spitzer, the author of books on historic guns and gun laws, and an expert for groups proposing stricter gun laws, predicts discussions about the Puckle and other little-known firearms soon could reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

What would Puckle think of all this posthumous attention? Mused historian DeLay, “I think he’d be shocked, but delighted.”

Write to Cameron McWhirter at Cameron.McWhirter@wsj.com