In his first term as president, Donald Trump resurrected tariffs as a tool of economic diplomacy, regularly deploying them as a lever to extract new trade deals from other countries. The result was a world trading system with a bit more friction, but it remained largely intact.

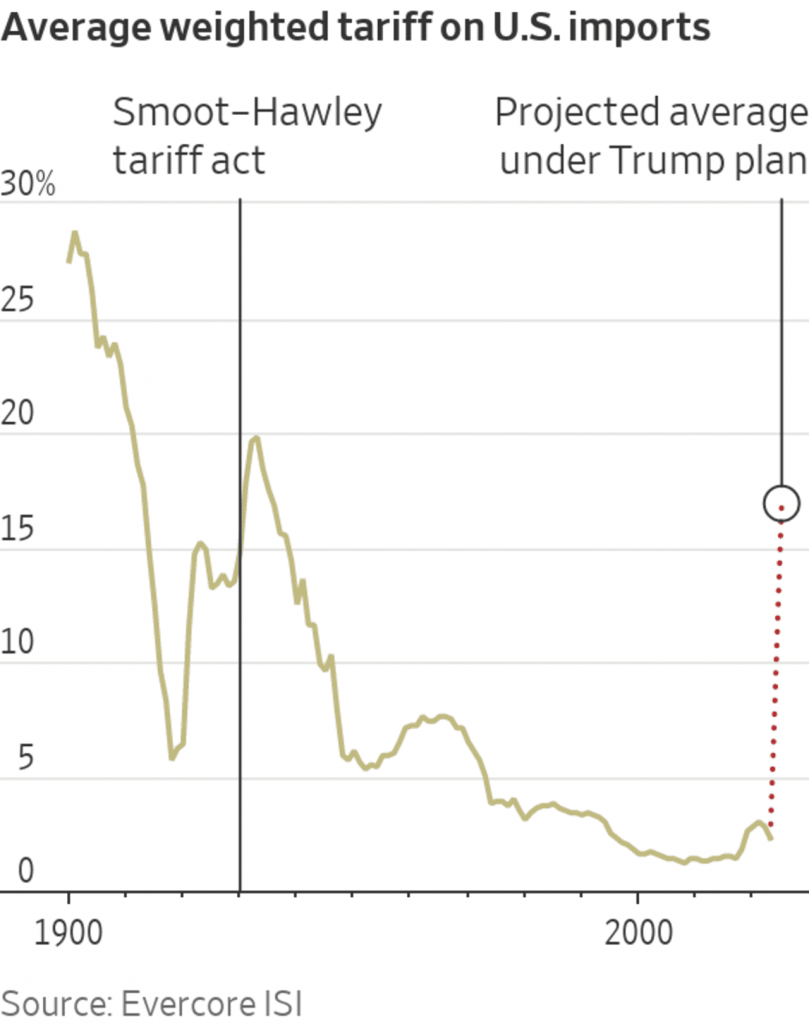

If Trump carries out what he has described on the campaign trail, his potential second term would be radically different. More than just a tool for negotiation, higher tariffs would be an end unto themselves. By one estimate, tariffs could reach their highest level since the 1930s.

In the short run, some prices in the U.S. would rise, and growth might suffer as consumers and businesses adjust to the new taxes on imported goods. The long-term impact depends crucially on whether other countries retaliate, and how far Trump would be willing to negotiate. The outcome could be anything from an all-out trade war, to a new trading system among U.S. allies united by their collective frustration with China.

A new Trump term may assume that “the global trading system of the late 20th century is not sustainable,” said Oren Cass, founder of American Compass, a conservative think tank that is close to Trump advisers and backs Trump’s tariff plan. “The endgame here isn’t some kind of negotiation where we all get back to 1995,” when the World Trade Organization came into force. Rather, it’s a “fundamental rebalancing.”

The free trade consensus that prevailed from 1995 until Trump’s election in 2016 isn’t going to return even if Vice President Kamala Harris , the Democratic nominee, wins. She may add to the mix of tariffs imposed on China during Trump’s first term and manufacturing support overseen by President Biden. But these would represent incremental changes, whereas a re-elected Trump could fundamentally remake the world trading system.

Trump’s plans remain shrouded in uncertainty. He has called for an across-the-board tariff of 10%, later suggested 10% to 20%, and at least once even said 50% to 200%.

He has proposed a tariff of 60% on goods from China, or maybe more. He has also proposed reciprocity, or U.S. tariffs that match those of its partners. That should spare Mexico and Canada, which under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement negotiated in Trump’s first term don’t charge tariffs on the U.S. But Trump has separately said autos from Mexico would face tariffs of 100%. Mexico imposes no tariffs on U.S.-made autos.

In short, no one knows what Trump has in mind.

If it turns out that the tariff on China is 60% and the rest of the world is 10%, the U.S.’ average tariff, weighted by value of imports, would leap to 17% from 2.3% in 2023, and 1.5% in 2016, according to Evercore ISI, an investment bank. That would be the highest since the Great Depression, after Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which triggered a global surge in trade barriers.

U.S. tariffs would go from among the lowest to highest among major economies. If other countries retaliated, the rise in global trade barriers would have no modern precedent, said Doug Irwin , a trade historian at Dartmouth College.

Higher tariffs would likely be around for years, even if a future president concludes they are a mistake. “These things are easy to impose and hard to remove,” said Irwin. “The project of removing the trade barriers that accumulated during the Great Depression took decades.”

The biggest question mark hanging over Trump’s plans is how much he would be willing to dial down tariffs in return for concessions. During his first term, centrist advisers moderated his more protectionist impulses, and Trump ended up using tariffs to renegotiate deals with trading partners.

The North American Free Trade Agreement became USMCA, South Korea agreed to amend the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and Japan lowered barriers to U.S. agricultural products.

Whether this would be the template for a second term, though, is unclear: He and his advisers have given mixed signals. Scott Bessent, former chief investment officer for Soros Fund Management and currently an adviser to Trump, said in an interview with Bloomberg in July Trump’s tariff plan wouldn’t be implemented all at once: “It would be phased in. And I also think that other countries would be given the opportunity to open their markets.”

Robert Lighthizer , who as trade ambassador authored Trump’s first-term trade strategy and who remains an influential adviser, has said the goal of tariffs should be the elimination of the U.S. trade deficit . That could mean high tariffs indefinitely, even if other countries grant concessions. Trump has said higher tariffs would raise money to lower other taxes, suggesting he, too, sees them as permanent.

Clete Willems , who served under Lighthizer and in Trump’s White House and is now an attorney at Akin Gump, said the likeliest result would be a blend of negotiation, and, ultimately, higher tariffs.

“We’re going to enter a higher tariff environment, but all the design decisions are open to discussion,” he said. “We’ve talked about Trump the tariff man. Let’s not forget Trump the dealmaker.”

Congress vs. the White House

In Trump’s first term, Congress, particularly Republicans, often pushed back against his protectionism. Four years later, the party has moved away from free trade; this year’s election platform backed Trump’s across-the-board tariffs. If Republicans emerge from next month’s election with control of the White House and both the House of Representatives and the Senate, they are likely to grant Trump substantial leeway.

Republicans are also eager to extend their 2017 tax cut, much of which expires at the end of 2025. Tariffs could offset some of the estimated $4 trillion cost over 10 years. While only Congress can permanently revise tariffs, various laws already give the president discretion to raise them indefinitely.

Republicans could tell themselves, “‘I don’t have to vote for it, it finances things I care about, and frankly, it’s not legislated, so it’s a lot easier to undo,’” said Rohit Kumar, a former aide to Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell now with PwC. Meanwhile, on CNBC last month, Jason Smith, the Republican who chairs the House’s top tax and trade committee, raised the possibility of writing Trump’s tariffs on China into law, which “can raise a lot of money, in the hundreds of billions of dollars.”

Republicans are much less enthusiastic about tariffs on countries other than China. But they are open to their use as a bargaining chip over measures some see as discriminating against the U.S., for example the European’s Union’s planned border fee on the carbon content of imports such as cement and steel, corporate minimum taxes and perhaps value-added taxes (imposed on domestic purchases including imports but not exports).

Canada and Mexico could be targeted when USMCA comes up for review in 2026. China could be pressed to fulfill the terms of the trade deal it reached in Trump’s first term. Countries with which the U.S. doesn’t run persistent trade deficits, such as Britain, might be treated better.

“I think it’s an opportunity for everybody to wake up and realize that we’ve got all kinds of tools to bring people to negotiations,” said Rep. Kevin Hern (R., Okla.), chairman of the Republican Study Committee, an influential group of conservative House Republicans.

If Democrats control one or both chambers in a Trump second term, they would be open to tougher action on China, one House aide said.

But they are adamantly opposed to Trump’s across-the-board tariff, which Harris has branded a national sales tax. “We’re going to do everything necessary to protect working families from getting hit with an economic wrecking ball, which is what the expanse of the Trump tariff program is all about,” said Senate Finance Committee chair Ron Wyden (D., Ore.).

Whether they could stop him is another matter. “I don’t need Congress. I’ll have the right to impose [tariffs] myself,” Trump said last month. In his first term he used existing statutes designed to punish unfair trade practices and protect national security.

Those might be too piecemeal if he wins a second term. He could instead turn to the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a 1977 law intended to sanction countries and individuals seen as national security threats such as Iran and Venezuela.

“It’s fast, and it can be across the board, theoretically,” said Greta Peisch, a trade attorney with Wiley Rein, who was general counsel for the U.S. trade ambassador under Biden. This would be a novel use of the law open to court challenge, she said. In 2019 , Trump threatened to use it to impose tariffs on Mexico for failing to stop illegal immigration to the U.S.

Harris, if elected, would likely continue Biden’s trade agenda, which keeps tariffs and other restrictions on China while largely sparing allies.

She is no free trade advocate, having voted against USMCA as a senator. A spokesman said Harris “will employ targeted and strategic tariffs to support American workers, strengthen our economy and hold our adversaries accountable,” but she wouldn’t use the broader tariffs Trump has threatened.

Question of retaliation

In a Trump administration, the economic consequences of his tariffs would depend on how high they ultimately are, and whether others retaliate. Tariffs are a tax, which importers usually try to pass on to their customers.

Some factors could temper this. Importers may shift sourcing to an unaffected country. Many companies shifted operations to Vietnam and Mexico to escape Trump’s first-term tariffs on China, easing the effect on prices. China also allowed its currency to drop, further diluting the effect.

For tariffs to benefit domestic manufacturers, as Trump intends, prices would have to rise, to incentivize consumers to shift away from imports and domestic companies to increase production.

Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from a range of countries in 2018 caused the metals’ prices to rise 2.4% and 1.6% respectively, according to the bipartisan International Trade Commission. This did help domestic producers: their annual sales rose $2.8 billion. But the hit to domestic companies that use steel and aluminum was bigger. Their production fell by $3.4 billion annually.

Economists think the broader tariffs Trump has proposed would similarly raise prices and, on net, hurt growth. In a recent report, Morgan Stanley estimated that a 60% tariff on China and 10% on everyone else would boost consumer prices by 0.9% and cumulatively lower economic output by 1.4%. In 2018, an internal Fed study concluded that a 10% increase in tariffs by the U.S. and all its trading partners would boost inflation by about 1.5 percentage points and lower economic growth by 1 percentage point for a year.

Once prices and the economy adjusted to the new tariffs, growth and inflation would likely return to their original trend. But over time, tariffs would also reorder patterns of trade. Indeed, one goal of the tariffs Trump imposed on China, and Biden maintained, was to diversify away from China as a supplier.

A U.S. Steel plant in Braddock, Pa., last month. Photo: Nate Smallwood for WSJ

Still, by erecting tariffs to everybody, U.S. exporters could suffer, amid higher priced inputs and potential retaliatory tariffs in foreign markets. The U.S. would attract less investment intended to serve the global market, its exporters would lose market share and trade would shrink as a share of GDP, Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, predicted.

This would make China a more attractive trading partner for some countries. South America would be particularly ripe for such overtures, analysts at Morgan Stanley said, noting China has reduced annual restrictions on imports from Brazil by about 90% since 2020.

Trump and his allies argue other countries wouldn’t retaliate because they need the U.S. market more than the U.S. needs theirs.

“This is exactly the history of Smoot-Hawley,” retorted Jennifer Hillman , a Georgetown University trade law expert. “There was a presumption no one would dare raise their tariffs on us. And what happened? Everyone raised their tariffs.”

In Trump’s first term, China, the European Union, Canada and Mexico all did retaliate; Japan and South Korea didn’t. If the EU is hit again, “they will analyze it, and then they will retaliate,” said Cecilia Malmstrom , who did just that as trade commissioner for the EU’s executive body during Trump’s first term. As in the first term, the EU would retaliate dollar for dollar, and seek to act with other countries, she said. The message would be, “We don’t want a trade war, but if you start it, we’re not going to sit silently by and watch.”

The WTO was set up as an independent arbiter to settle trade disputes. But under Trump and Biden, the U.S. argued the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism was overstepping its authority and has refused to let it function. This raises the prospect of a destructive cycle of tariffs and retaliation between the U.S. and its trading partners, with no international arbiter to step in.

A study by the Peterson Institute found that trade flows could be permanently reduced between the U.S. and major trading partners by 1% to 4%, depending on retaliation.

Yet advisers to Trump have raised another scenario if Trump is re-elected: that the U.S. ends up with a set of tariffs for China, and a different, much less pervasive set of tariffs for allies that share the U.S.’ mistrust of China. In effect, it would once again become the hub of a trading system among market-oriented democracies as it was from the 1940s until the end of the Cold War.

The WTO “failed to evolve and modernize, and to deal with the issue of China,” said Willems, the former Trump White House official. “What takes its place? Some form of plurilateral negotiation with the G-7”—the seven largest market economies—“plus some core allies, like Australia and South Korea, maybe some surprising ones like Costa Rica, willing to adapt to a more market oriented, forward-leaning ambitious agenda.”

There are two reasons U.S. allies may prefer this to the trade war scenario. One is that they, like the U.S., are increasingly frustrated with and worried about China. It is sending a growing tidal wave of cheap manufactured exports into their markets through a panoply of policies the WTO has been unable to curb, from suppression of domestic consumption to pervasive state support for national champions and technology theft.

“The scale and magnitude of what China has done is beyond what a rules-based system can deal with,” said Hillman.

The second is that the world has become more dangerous since Trump was last in office, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s belligerent behavior toward its neighbors. Allies on the front line, including Japan, Germany and South Korea, need the U.S. security umbrella more than ever, and may thus be less inclined to respond to the economic provocations of a re-elected Trump.

Said Willems: “There are plenty of instances in history when we had tension with partners and allies and we were able to get past that and focus on the big picture.”

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com