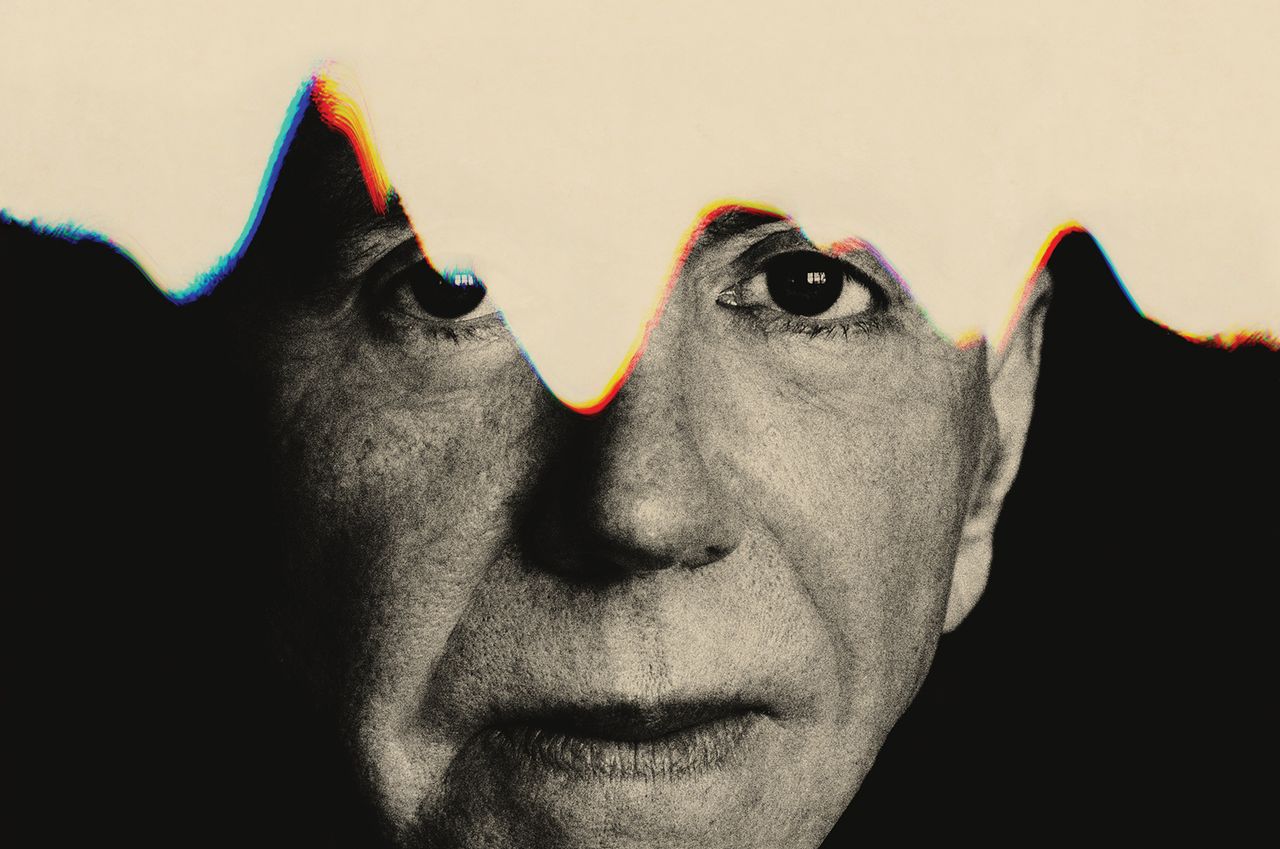

THE LEGENDARY New York art dealer Brent Sikkema was tangled up in an ugly divorce when he got on a plane to Rio de Janeiro before Christmas last year, looking for a fresh start. With its beaches and bossa nova, Rio offered an escape, a rollicking hot spot where the 75-year-old hoped to unwind and have some fun.

Brent had long held sway over a cerebral corner of the New York art scene, promoting women and diverse artists in the early 1990s when few galleries or museums exhibited either. While some of his peers planted mega-gallery franchises the world over, Brent anchored his Sikkema Jenkins & Co. at a single spot in SoHo, then Chelsea, where he and his gallery partners cultivated artists including Kara Walker , Mark Bradford and Jeffrey Gibson . Privately, friends gravitated toward his wicked sense of humor, a zest that extended to an ebullient social life, often populated by a revolving door of lovers. “He liked younger men,” says his friend, the artist Vik Muniz .

Now, landing in Rio, Brent was trying to move past a personal low point. Despite his outward success, close friends say he had been emotionally drained after nearly two years of hashing out a divorce settlement with his estranged husband, with whom he had a 13-year-old son. In Rio, he could spend a few weeks relaxing, maybe walk along Copacabana beach to meet locals or meditate.

Brent spent Christmas Day at the home of Muniz’s parents, who lived a few doors down from his own two-story vacation home near Rio’s lush botanical garden. Muniz was pleased to find Brent sanguine, regaling the group with his plans to spend more time in Brazil. He held up cellphone photos of an apartment he’d just bought in the tony Leblon neighborhood, which he hoped to furnish with vintage Italian lamps and midcentury Brazilian furniture. He’d brought about $55,000 in cash, mostly to shop. “He seemed well again,” Muniz says. “He was the last person to leave.”

Two weeks later, Brent’s lawyers got word from an appraiser that a long-awaited piece of information needed for a divorce settlement was finally ready, according to a document reviewed by The Wall Street Journal . This meant his ordeal might soon be over.

On Saturday, January 13, Brent stepped out of his house, white-haired and pale and dressed in a T-shirt, shorts and flip-flops. He carried a large tote bag. He likely didn’t notice the silver Fiat Palio parked across the street—or the man within, watching him intently. At 4:36 p.m., Brent returned, passing beneath his arched doorway.

Two days after that, a friend who managed his household bills stopped by to check in. This friend, lawyer Simone Nunes, grew worried after noticing he hadn’t been active on WhatsApp since Saturday night. Using her own key, she encountered a gruesome scene: The famed art dealer was lying naked on his bed, stabbed 18 times. Many of the wounds were to his chest and face.

Within hours, Brent became the focus of a high-profile police investigation, reverberating across a horrified international art world that revered him. The murder weapon, a santoku knife, was found right away, in the kitchen. The killer, police say, had washed it and put it away.

Authorities scanning security-camera footage of the street spotted a tall, lanky young man who appeared to have spent much of Saturday idling near Brent’s house. At 3:43 a.m., the man entered the home and left 14 minutes later, pulling off gloves as he got in his car and drove away.

As the manhunt spread, Brazilian press initially suspected a robbery. Nunes told police that a wad of cash Brent had left atop his dresser was missing. By Thursday, January 18, police narrowed their chase to a suspect they found sleeping in a different car at a gas station 560 miles away: Alejandro Triana Prevez, a 30-year-old delivery driver who had moved to Brazil from Cuba a few months before.

The day after the arrest, the dealer’s husband, Daniel Sikkema, 53, posted a photograph of a black rose on his Facebook, writing: “Our son and I cry for you without tears, we cry for you in the way that hurts the most.”

Prevez initially denied any involvement in the crime, then told police he had been drugged by a Colombian tour guide who had stolen his car.

But two weeks later, police said his story changed entirely: He had killed Brent—and he told police Daniel had hired him to do it.

Suddenly, what had seemed like a robbery gone wrong had become something more sinister. Daniel, sharing his side of the story for the first time since the murder, denies that he had anything to do with his husband’s death: “I am innocent and I trust in the justice system.” Prevez, he adds, is unreliable. As the case makes its way through the courts in Brazil, back in New York, everyone wants to know: How did it come to this?

This account is based on interviews with Brent’s friends, lawyers for Daniel and Prevez, and a review of documents related to the case, including a 23-page jailhouse account handwritten by Prevez and a 1,056-page report amassed by the Brazilian police.

BRENT SIKKEMA was 59 years old and had already carved out an outsize life as one of New York’s most respected art dealers by the time he met 37-year-old Daniel Garcia Carrera during Art Basel Miami Beach in late 2007.

Born in 1948, the son of tavern owners in Morrison, Illinois, Brent studied photography and graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1970—the same year Daniel was born in a tiny town in the Cuban province of Camagüey. While Brent was busy overseeing exhibitions at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, then running Boston’s Vision Gallery, Daniel was fleeing a troubled childhood and doing whatever he could to survive in Havana and later Madrid, including sex work, according to Daniel’s 2006 memoir.

By 1991, Brent settled in New York. Initially, he intended to show photographers in SoHo, but the city expanded his artistic interests and he soon pivoted to a broader gallery model. Called Wooster Gardens and then ultimately Sikkema Jenkins, his space became a lively undefined art incubator.

“He was faithful to artists, and they loved him because he was brilliant at talking with them about theories and approaches,” says private dealer Olivier Renaud-Clément. After work, he and Brent sought out the same nightlife, going to sex clubs and swapping ribald stories, Renaud-Clément says.

To Brent’s friends, Daniel knew nothing about art. But “Danny,” as Brent called him, made him happy. Everyone could tell. Daniel was living in Miami, but Brent flew him to New York every weekend. After a couple of months, Brent asked him to move in, initially paying his rent in Miami in case they didn’t work out. Friends say Brent often paid his lovers’ bills.

In 2010, the pair became parents via surrogate, and on the third birthday of their son, they got married. Brent reveled in telling people that his own name was listed under “mother” on Lucas’s birth certificate, but Daniel assumed the main caretaking role. “Organizing Mickey Mouse birthday parties and all that kid stuff didn’t come naturally to him,” Muniz says. “He left all that to Daniel.”

Over the next few years, the new family bought the two-story townhouse in Rio, on that leafy block. The couple also had two places in Havana : a home on Avenida del Bosque and a nearly $400,000 penthouse apartment elsewhere in the city. Since the U.S. trade embargo forbids Americans from buying property there, Brent couldn’t buy the penthouse in his name and Daniel was forbidden as a Cuban from buying two properties in the same city, so they put the home in the name of a local cousin. In 2019, Daniel posted an ad on Facebook seeking a caretaker for the Havana house. He hired Alejandro Triana Prevez, a young former teacher at a Havana polytechnic school.

Before the pandemic, Daniel says he and Lucas spent a lot of time at the home in Havana with Prevez. The caretaker grew attached to Lucas, kicking around a soccer ball with the boy. Brent, who had previously traveled back and forth to Cuba, started hanging back in Manhattan more often. When Daniel and Lucas returned during the pandemic, the trio struggled in part because, Daniel says, Brent had started using more drugs in their absence. Renaud-Clément says his friend felt lonely and turned to drugs to cope. Daniel eventually floated the idea of the family moving back to Cuba for good, but in March 2022 Brent said no, according to a court filing reviewed by The Wall Street Journal . Brent then told friends he was livid after finding out Daniel had gone ahead and informed Lucas’s school that the family was moving to Cuba. Brent said in the filing that the desired move sparked a heated argument, after which he went to a hotel to cool down. When he returned, he said, Daniel and Lucas and $10,000 from their apartment safe were gone.

Daniel says that at one point Brent agreed to move, and he says he emailed the school because he typically handled child-rearing decisions.

“THE DIVORCE CAME out of nowhere,” Brent later wrote in an email to a friend included in the Brazilian police report. “Danny took Lucas and disappeared, and I was in a total panic believing that he was taking him to move in all his splendor to Havana. I was working with the State Department child abduction program and it was awful—as they said—if that guy gets your son to Cuba, it is game over.”

Daniel and Lucas soon resurfaced safely in the U.S., but the tensions escalated. While friends of both men say the couple was known to have an open marriage, the men started accusing each other of cheating and other unsavory behavior. Brent accused Daniel of unsuccessfully trying to withdraw $200,000 from Brent’s Wells Fargo account.

Daniel then told Manhattan police his husband’s recreational drug use had gotten out of control, which Brent denied. Brent complained in his email that Daniel told police he was allegedly “leaving bowls of cocaine all over the apartments.” Brent denied leaving drugs about. Daniel also told police that Brent was planning to take a gun to John F. Kennedy International Airport to “kill people,” Brent wrote. The art dealer didn’t even own a gun, he said.

As the fighting intensified, Brent changed the locks on their apartment. Daniel discovered this after failing to get inside while Brent was out of town. When Brent returned, a Manhattan detective informed him he had a warrant for his arrest—for allegedly wrongfully evicting his spouse, Brent wrote in a court filing. Daniel’s lawyers confirmed Daniel called the police after being locked out. Brent was questioned, but never charged.

Next came the restraining order. Daniel filed for an order of protection against Brent, again raising Brent’s alleged drug use to New York’s Child Protective Services by accusing his husband of using drugs in front of Lucas, which Brent denied. Six months later, the agency sided with Brent, ruling that the “allegations have been unsubstantiated due to lack of credible evidence.” A family court judge granted the couple joint custody until the divorce was finalized, Brent wrote.

“I think he knew this was the way to create a bad image of me,” Brent wrote of his ex, “and at the same time break my heart as Lucas IS my heart and I hold nothing but love for him.”

In May 2022, Brent updated his will with help from James Deaver, a lawyer and longtime friend. He disinherited Daniel and named Lucas as his primary beneficiary.

The matter of Brent’s net worth came to the fore as they fought over the terms of any divorce settlement. Deaver said Brent’s entire net worth amounted to less than $20 million at the time, but Brent was only obliged to split whatever wealth he amassed during the course of the marriage. Among his assets were a $2.8 million Chelsea apartment he’d bought in 2007, a $1.7 million modernist house on Fire Island, his ownership interest in the gallery and artworks he’d bought over the years. The fate of the homes in Cuba remained in flux.

Daniel wanted to settle for a $6 million payment, according to an email he sent to Brent, though Daniel says it wasn’t a formal request. Deaver said Brent rejected the request as “excessive” because the dealer amassed the bulk of his fortune long before the couple married. Either way, they couldn’t settle until a third-party appraiser determined whether Brent’s gallery had appreciated in value during the marriage—a key finding that didn’t come through until Brent was in Rio. Until then, they had to wait.

In the meantime, Daniel sought, but failed, to get Lucas’s U.S. and Spanish passports. Last summer, a court granted Brent the right to hang onto them. Daniel was also forbidden from taking Lucas to Cuba until the boy turned 18.

THEN ONE DAY , out of the blue, Daniel got a WhatsApp message from Prevez, his former caretaker in Cuba. Prevez had since moved to São Paulo and wanted to catch up, according to his police statement.

Prevez said Daniel told him about the ongoing divorce. Then, he told police, Daniel made him an offer: $200,000 and a free place to stay in Rio in exchange for killing his ex.

It was a tempting offer, Prevez said in an account handwritten in blue and green ink from jail. The Wall Street Journal reviewed the account, titled A Life for a Life , through the lawyer who represented Prevez until recently. Prevez hoped to turn it into a book.

Like Daniel, Prevez had struggled for years to scrape together a living in Cuba, repairing bicycles by day and working as a night security guard. In September 2022, he moved to Brazil in hope of a better salary.

In the account, Prevez wrote that he had never killed anyone before, adding that he barely knew Brent, though Daniel’s lawyers later disputed this. But Prevez wrote that Daniel started complaining regularly to him about Brent. Prevez says one alleged incident particularly enraged him: He says Daniel told him that once, during a trip to Paris, Lucas was left in tears after overhearing Brent with an escort in the hotel room next door. Daniel confirmed he told this story to Prevez.

Prevez told Daniel he “would think about the proposal,” he later told police. After that, money orders started coming his way regularly from New York, he said. The funds, usually in $300 to $500 increments, appeared to be wired by a stranger named Pedro Mainer using a Western Union in Queens. Brazilian investigators later linked the funds to an account registered to Daniel’s cellphone with a home in Queens owned by his former housekeeper. Prevez said Daniel also mailed him a key to the home in Rio and encouraged Prevez to get a cellphone that would allow them to communicate via WhatsApp.

Prevez told police he went to Rio twice last year—first to plot the crime, then to commit it. But during the second visit last December, he got nervous and backed out. Prevez told police that Daniel grew upset, allegedly telling him, “If you don’t want to do this, don’t do it, but forget that I exist.”

The money orders stopped trickling in. Daniel’s lawyers say these communications and payments were merely back pay for Prevez’s work in Havana.

Prevez says he took a job making deliveries for an online marketplace known as Mercado Livre in a borrowed Fiat Palio, but he wasn’t earning enough to support his own family in Cuba. He went back to Daniel, he told police, and agreed to go to Rio one more time—after Christmas, when he said Daniel told him Brent would be in town.

On January 13, police say, Prevez parked the Fiat Palio on Brent’s block by 2:30 p.m., a crossbow in the back seat. He told police he had bought the $389 Jag 2 online as a potential undefined murder weapon.

“It’s like a rifle, but you just get one shot. The most important thing, though: it’s silent,” Prevez explained in his jailhouse account. But at the last minute, he wrote, he left the weapon in the car and walked up the stairs to Brent’s bedroom. Referring to himself in the third person, Prevez wrote, “He moves to the side of the bed silently, trying to breathe calmly but failing.” He then described how he used a knife from the dealer’s kitchen. “He closes his eyes and throws himself down on top of the victim, letting the knife go in.”

He wrote that he stabbed Brent four times, although the autopsy report later found 18 stab wounds. Afterward, Prevez wrote, he apologized and covered Brent’s body with a sheet, washed the knife and left.

Minutes later, Prevez called a Brazilian WhatsApp number registered to a woman Daniel knew in Brazil, though the call filtered through a New York IP address, police said. When Prevez got a call back from the same number the next morning, he told police, the caller was Daniel, telling him to delete their call log on his cell. He didn’t.

Daniel denies that he spoke to Prevez at any point after Brent’s death.

Prevez told police he returned the borrowed car in São Paulo and bought another with money he alleges Daniel sent him. He told police he didn’t take the cash sitting on Brent’s dresser. Prevez said he drove north, in hopes of eventually snaking west to Paraguay. He had just pulled over at a gas station in the state of Minas Gerais to get a little sleep.

He woke up surrounded by police.

IN A TWIST , Prevez now has a new lawyer, who says his client’s previous statements to police and written account were given under the assumption that they would be part of a plea bargain. The lawyer says Prevez may prepare a new statement down the line.

Meanwhile, Daniel, through his lawyers, says the Brazilian police have got the story all wrong, that Prevez’s backstory was fed to him by the police after they gleaned details about the divorce from Deaver, the executor of Brent’s estate. Deaver says he just responded to investigators’ requests for information.

Under Brazilian law, Prevez could earn a reduced sentence if he acted on another’s paid behest. Daniel says he suspects his former employee was encouraged to point the finger elsewhere, anywhere.

“I hope that, based on evidence and not false allegations, what really happened will come to light, although Lucas and I will have to deal with the emotional damage this has caused for the rest of our lives,” Daniel says in a statement.

Both Daniel and Prevez allege that the Brazilian police left potential leads unpursued. Brent’s bank records and phone calls weren’t examined, which could matter because these records might reveal whether he interacted with Prevez or others in the days leading up to the crime. Rômulo Assis, the case’s lead police investigator, says his team couldn’t unlock Brent’s phone because no one knew his password and attempts to use facial recognition, holding up the phone to Brent’s face postmortem, failed because he had been dead too long. Assis conceded he didn’t seek Brent’s bank records. He says he was more concerned about finding Prevez, based on the security-cam footage, and issuing a warrant for Daniel before he had a chance to flee to Cuba. “I believe Alejandro killed Brent for money,” Assis says, “but the number of stab wounds shows that it was also a crime of passion. ”

On February 7, Brazilian police handed down indictments for “qualified homicide” against Daniel and Prevez, saying they believed Daniel stood to benefit from Brent’s death.

According to New York law, Daniel could seek a third of Brent’s net worth as the surviving spouse—likely more than he would get in any divorce settlement. Daniel’s lawyers say they intend to claim his share as a surviving spouse.

Police have since issued a preventive arrest warrant for Daniel, which has been given to Interpol. Brazilian authorities say they’re conferring with their U.S. counterparts now over whether the U.S. will extradite Daniel or pursue its own investigation.

The matter of Lucas’s passport continues to flare up. Deaver told Brazilian police he got a call from Daniel’s divorce lawyer a week after the murder, asking to enter Brent’s New York apartment to collect Lucas’s U.S. passport. Deaver refused, saying he didn’t yet have the authorization to let anyone in. Deaver told police that Daniel then emailed him five days later, asking for both Lucas’s expired Spanish passport and his active U.S. one, telling the executor that his son “has a trip to Italy” with his traveling soccer team. Again, Deaver declined. Daniel says he simply wanted his son to go on that trip in late March, and Deaver wouldn’t help.

The day after Brazil indicted Daniel, he walked into a Manhattan post office and tried to renew his son’s U.S. passport, writing in the application that the other one had been lost “after a trip with his other father to Europe,” according to a court affidavit submitted later by the FBI. On March 20, the FBI arrested Daniel for allegedly committing passport fraud. He now wears an electronic ankle bracelet.

In New York, a chill set in against Daniel. He wasn’t invited to the gallery’s memorial service held in March. Kara Walker , whom Brent had discovered after art school, spoke at the service through tears. “Brent had taken a gamble for me, and I would do the same for him,” Walker told the group. “He never let me down.”

Daniel says he asked his son if he wanted to go to Rio to spread his father’s ashes in the botanical garden Brent loved. But, he says, Lucas never wants to go to Brazil again, ever.

Write to Samantha Pearson at samantha.pearson@wsj.com and Kelly Crow at kelly.crow@wsj.com