When Loren Levy’s son Simon was little, he loved watching “Thomas & Friends,” the British cartoon about a talking train. That changed when Simon turned 8 and began watching videos on YouTube.

“Now, all he wants to do is watch gamers and basketball clips and highlights on YouTube,” said the South Orange, N.J.-based human-resources consultant. She can’t persuade him to watch anything else.

The Levy family learned what has become clear across the media industry: When it comes to children’s entertainment preferences, YouTube trumps all.

Netflix’s share of U.S. streaming viewership by 2- to 11-year-olds fell to 21% in September from 25% two years earlier, according to Nielsen. Meanwhile, YouTube’s share jumped to 33% from 29.4% over the same period.

That reality is changing major streaming services’ approach to children’s entertainment, from what shows and movies they make to where they release them. Many are pulling back on investments in children’s content, and some streamers have started content for young viewers on such platforms as Google-owned YouTube and Roblox.

Entertainment companies recognize that youths are increasingly drawn to short-form content, not longer shows on streaming services, said Michael Hirsh, co-founder of WOW Unlimited Media, a Canadian animator.

“These viewers are watching on their iPads or on other platforms that have moved to shorter and shorter segments, and it’s a real issue for the streamers,” said Hirsh.

When Toronto-based Spin Master released its animated children’s film about a school where students learn to ride unicorns, it made its debut on Roblox in September and was released on Netflix about two months later. The studio also released half of “Unicorn Academy” on YouTube in October, and Netflix released the second half of the movie on its own YouTube channel at the same time.

“It’s really about following the consumer,” said Jeremy Tucker, global chief marketing officer at Spin Master, the studio behind major children’s franchises including “PAW Patrol.”

To get the rights to one of the biggest preschool animated hits, “CoComelon,” the streamer agreed with the show’s creator, Moonbug, to let the show remain on YouTube, where it started and continues to air. While the streamer has long had children’s channels on YouTube, such as Netflix After School, it has been resistant to putting full episodes of children’s originals on the platform for fear of cannibalizing its audience, according to people familiar with the situation.

That has started to shift recently. Last month, Moonbug, with Netflix’s blessing, released the first episode of a CoComelon spinoff series, called “CoComelon Lane,” on YouTube a week before the series came to the streamer.

Sony, with Netflix’s permission, in recent weeks launched a YouTube channel of episodes and clips from its “The Creature Cases” preschool series on Netflix to help draw a bigger audience, according to a person familiar with the situation.

As recently as a few years ago, entertainment companies such as Netflix and Warner Bros. Discovery, then WarnerMedia, ramped up their animated divisions. They saw cartoons—and youth programming in general—as essential to keeping subscribers as families want to keep services with shows their children watch.

Research showed that families with children canceled their service at a lower rate than households without them, said Tom Ascheim, a veteran Disney children’s programming executive hired by Warner in 2020 to oversee a new division creating shows for children and young adults.

“Every piece of data showed that households with children watch more and were less likely to churn,” said Ascheim, who recently co-founded Pith & Pixie Dust, a consulting firm that works with companies on attracting younger audiences.

Warner executives found that if young children watched franchises like Batman, the longtime value of that household as a subscriber was three times as large as one that hadn’t watched them, said a person familiar with the situation. Children’s shows were also thought to attract global audiences because the story lines are often universal and animation is easy to dub in foreign languages.

Under Ascheim, Warner’s new kids and young adult division planned a host of new shows for its linear networks and for Max.

Then austerity set in. After Warner merged with Discovery in April 2022, it made cuts to its animated and children’s division as part of an effort to reduce costs and pay down debt.

Ascheim’s position was eliminated, and many of the cartoons planned for what is now Max were shelved or licensed to competitors. The company pulled episodes of “Sesame Street” from Max to save money and has said that while it will continue to offer some children’s programming, Max’s focus is more on adults and families.

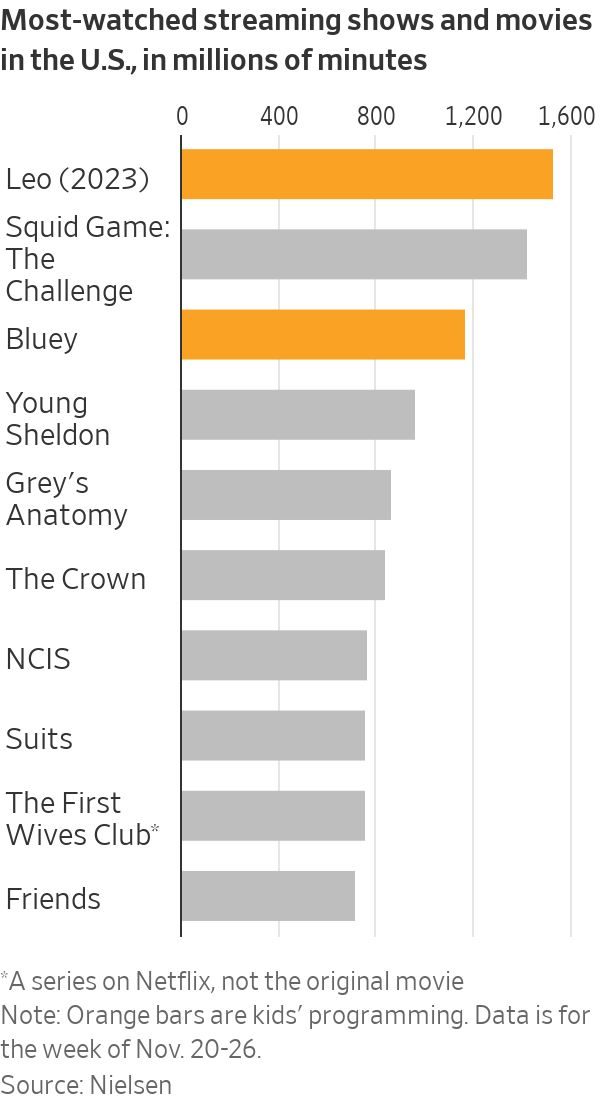

Netflix has also slimmed down its slate of animated children’s originals, opting instead to rely more on third parties such as Skydance Animation, with which it just signed a multiyear deal to do animated films. Now, Netflix is focusing its youth programming resources on bigger swings, such as the animated film “Leo,” starring Adam Sandler, its biggest animated debut ever in terms of views.

The eight largest U.S. streamers, including Netflix, Warner’s Max and Amazon Prime Video, added 53 originals catering to children and families in the first half of the year, down from 135 for the first half of 2022, according to Ampere. That represents a decrease of 61%, compared with a 31% decrease in overall originals across these streamers for the same period.

Among the challenges streamers have confronted in making children’s content is kids’ tendency to seek out characters they know. It is hard to make new ideas break through.

“It is really difficult to build new franchises, especially in this fragmented streaming market,” said Jeff Grossman, head of programming for Paramount+, which features such franchises as Nickelodeon’s “SpongeBob SquarePants, “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” and “PAW Patrol.” Children’s programming is consistently the most-watched content on Paramount+.

That is particularly true when these companies are going up against Disney, whose Disney+ streaming service is still core to families with young children, including such big hits as “Bluey,” major animated films and Mickey Mouse.

It takes time to create animated fare, which means entertainment companies have to approve multiple seasons if they want to keep their audience before they get too old to watch the show anymore.

That is what happened with Caleb Mogil, who at 3 years old couldn’t stop watching “Charlie’s Colorforms City,” an animated series on Netflix. In the show, Charlie, a boy made out of the Colorforms stickers, takes viewers on adventures with shapes and colors.

Caleb loved the first season, but the second season wasn’t released for 2½ years, said his father, Ben Mogil, who is managing director of Qualia Legacy Advisors and has worked with animation studios.

By that time, Caleb had already moved on to the animated version of the British comedy “Mr. Bean,” on Amazon Prime Video.

Write to Jessica Toonkel at jessica.toonkel@wsj.com