“I came here to keep the memory of this event alive in Germany. Here, in this place, I feel deep sorrow and shame.”

These were the words used in April 2000 by the then President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Johannes Rau, in a speech he made in Kalavryta, where hundreds of men were executed on 13 December 1943 by the occupying Nazi forces.

TO VIMA, 05.04.2000, TO VIMA | TA NEA Historical Archive.

According to cross-referenced historical sources, a total of 694 murders were committed by the Nazis in the Kalavryta area between the 5th to 16th of December 1943, with 487 committed in Kalavryta itself.

Just two years after this unspeakable tragedy, TO VIMA of 13 December 1945 wrote:

“This day will always serve as a reminder to Greeks everywhere, and to the entire civilized world, of one of the most awful of German crimes. Kalavryta and nearby Kerpini, Mazeika, Soudena, Rogoi, Pagrati, Akrata, Zachlorou, Skepasto, Strezova and other villages in the area have gone down in history as sites of martyrdom.”

TO VIMA, 13.12.1943, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive.

Bloody Traces

In 2004, Stathis N. Kalyvas, Professor of Political Science at the University of Yale, presented Hermann Frank Mayer’s book From Vienna to Kalavryta. The bloody traces of the 117th Commando Division in Serbia and Greece, which was published in Greek only, in an article in TO VIMA of February 15th.

Stathis N. Kalyvas writes:

“Hermann Frank Mayer is not a professional historian but his book would be the envy of many professional historians.

“It is an exemplary military history based on many years of research employing multiple sources, both archival and non-archival. Shedding a unique light on the German occupation of the Peloponnese, it brings some new facts to light while also dispelling a good many myths.

(…)

“Mayer has undoubtedly written a fine book on the German occupation, which will henceforth be an indispensable aid to the study of the history of the 1940s.

TO VIMA, 15.02.2004, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive

The 117th Division

“The 117th Jäger Division was never a particularly effective, far less elite, unit. It was “born” as the 717th Infantry Division and consisted mainly of patchily trained middle-aged Austrian conscripts armed with obsolete weapons. It saw action for the first time in the summer of 1941, in Yugoslavia, where it was attacked head-on by the partisans, suffered significant losses and retaliated with mass civilian executions.

“In March 1943, it was reformed as the 117th Jäger Division, given a new commander—the determined and tough Colonel Karl von Le Suire, and sent to the Peloponnese to face an expected Allied invasion that never materialized. In parallel, ELAS, the military wing of the communist-sponsored EAM resistance organization, had been extending its guerilla warfare since December 1942. By autumn 1943, it had successfully eliminated right-wing resistance groups made up of former officers in the Greek army and taken control of the highlands across the entire peninsula. After the Italians capitulated, ELAS filled the power vacuum they left behind and extended its dominance over the entire Peloponnese, with the partial exception of several urban centers.

The clash in Kerpini

“In an attempt to control a situation that was rapidly spiraling out of its control, the weak German division undertook a series of operations, one of which centered on Aigio’s mountainous hinterland. It was in the context of this operation that German forces were ambushed on 16 October 1943 near Kerpini, resulting in the capture of 81 men.

“There followed a period of negotiations between the two sides aimed at arranging a prisoner exchange and avoiding reprisals. The partisans demanded the release of 50 Greeks for every German prisoner, possibly including Nikos Zachariadis, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Greece from 1931 to 1956, who was being held in Dachau at the time.

“Rejecting these proposals, the Germans launched a major effort in early December to locate the prisoners. The operation was accompanied by a number of atrocities, which culminated in the Kalavryta massacre. On 7 December, as the Germans were getting close to their position, the guerrillas decided to execute the prisoners.

“The evidence provided by Mayer leaves no doubt that the execution was ordered and not committed in the heat of the moment, and that it preceded the Kalavryta massacre, contrary to claims made later and repeated to this day.

“When the Germans discovered that three of their wounded comrades who had been transferred to the Hospital of Kalavryta after the clash in Kerpini, had also been executed, they decided to make an example of the inhabitants of Kalavryta, who had played no part in the executions. The massacre took place on 13 December and Mayer’s description is, if anything, rendered more shocking still by his avoidance of the unnecessary melodramatics that often accompany such descriptions (indeed, one of the book’s own prefaces contains just such an account).

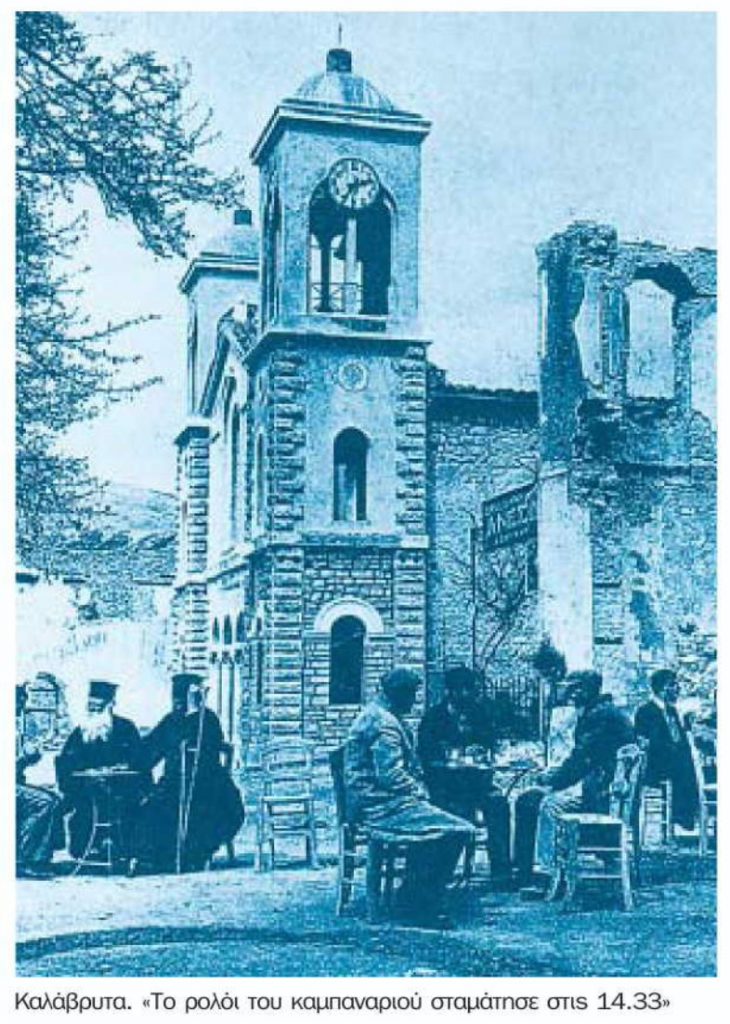

TO VIMA, 15.02.2004, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive. “Time stopped at Kalavryta at 14:33.”

The Kalavryta massacre

“A thorough cross-check of the sources reveals a total of 694 documented murders between December 5 and 16, of which 487 were committed in Kalavryta itself. In other words, the figure of 1,300 executed Kalavryta residents which took root in the post-war period was revealed to be made up.

“At the same time, the book disproves a number of other myths that had accumulated over the years, including claims Greeks participated in the executions, the case of the “Austrian soldier” who supposedly saved the lives of hundreds of women and children by opening the door of the school where they were being held, and the existence of a ‘notorious’ German officer by the name of ‘Tanner’ who is described as directing the execution in dozens of accounts, but turns out to have been a lowly corporal called Conrad Denner who played only a minor role in the decision-making. These clarifications do not change the substance of the event, but they help to banish numerous fictions that bear no relation to reality.

The reactions of the survivors

“Mayer also touches on a highly contentious issue: the reactions of the population of the martyred city. As a series of studies conducted in Italy and elsewhere have shown, far from condoning the partisans’ actions, the survivors of German reprisals often held them jointly responsible for the reprisals their actions caused. Post-war, this reaction was covered over in the name of ‘national unity’.

“Something similar seems to have happened in Kalavryta: a woman recalls how ‘some partisans showed up that day… All the women hurled themselves at him, wanting to kill him, but he escaped and shouted back at them, “What are we supposed to do with you. The Germans got there before us, otherwise we’d have done it ourselves.” The next day another rebel came down, whose father and brother had been shot. His mother cursed him, called him a murderer, and told him she never wanted to lay eyes on him again… Two or three of the women protested so violently, the partisans took them away and locked them up in a camp. A few weeks later they were released and returned to Kalavryta’ (p. 424). It is truly difficult to describe these people’s ordeal.

German soldiers in Kalavryta as it burns.

“The bloody progress of the 117th Division did not stop at Kalavryta. In all, it caused the deaths of over 4,000 Greeks, mainly civilians (these figures do not include the victims of the politically-motivated fighting between different Greek factions, which mainly took place in 1944). In comparison, around 1,100 Germans paid for their presence in the Peloponnese with their lives. Ultimately, the 117th Division met a miserable end during its retreat through Yugoslavia, where it suffered terrible losses.

Documentation

“Mayer’s contribution is manifold, as his exemplary and multifaceted documentation comes hand in hand with a pared-down writing style that lets the facts speak for themselves. Perhaps the work’s only weakness, if it can be described as such, relates to its description and documentation of the dynamics within the Greek population and its various factions and organizations.

“Mayer certainly provides important information from the German and English archives, which he supplements with oral accounts he gathered himself with the help of Greek translators, but he does not delve far below the surface here. Which is only to be expected, as his analysis centers primarily on the German side. But in this area, too, his research forms the basis for a series of new and fruitful questions.

Quality control

“It should also be stressed that Mayer’s contribution extends beyond the narrow limits of historiography. In so doing, it confirms, firstly, that a comprehensive and in-depth factual reconstruction of the events of the 1940s is the only way in which those events can be understood and interpreted. And, secondly, it highlights a fundamental weakness in the Greek historiography: namely, a widespread tendency to transform serious inaccuracies into self-evident truths through their perpetual reproduction.

“This problem is due in part to the enormous degree to which amateur historians are represented in the historiography, and to the absence of the sort of effective ‘quality control’ from which professional historians benefit, which would allow the average reader to safely distinguish between serious research and fiction. Finally, this book serves as a reminder of the importance of the research ethos.

“Mayer was motivated to start researching the German occupation of Greece by a personal experience: the execution of his father, a soldier in the Wehrmacht, by ELAS partisans, which he describes in a clinically clear but somehow still emotional way in his first book (The Search: Human fates in the Greek resistance, 1941-1944, in Greek).

“Within a few years, however, he had managed to surpass this entirely natural emotive response and produce a noteworthy work that steers clear both of the tendency to indirectly justify the perpetrators (which is still prevalent in some German circles) and the easy route of substituting melodrama for detailed and in-depth documentation. He thus delivers a historical work which manages to be both accurate and objective without losing an iota of its power.”