It was February 20, 1968. In the stillness of dawn, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake erupted just south of Agios Efstratios (colloquially Ai Stratis). Terror and death swept across this small island in the northeastern Aegean—an island already burdened by a dark past, having served for decades as a place of exile for communists during turbulent times in Greek history.

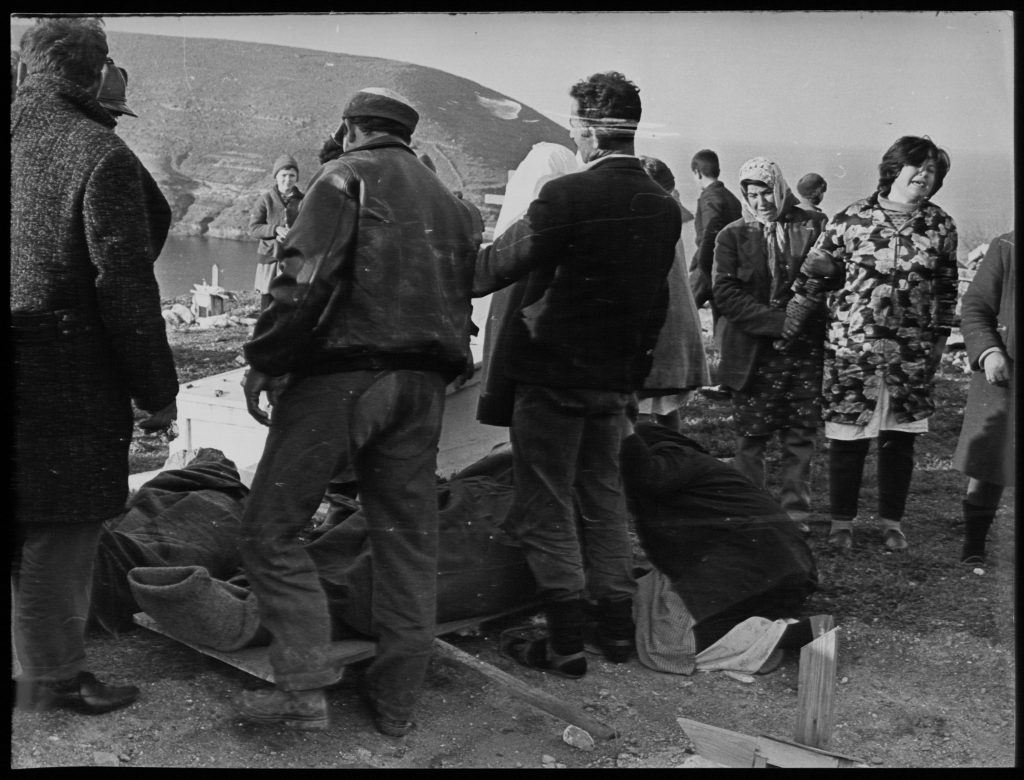

The devastation was absolute. Twenty lives were lost. Thirty-nine people were injured. The first reports painted a grim picture: Agios Efstratios had been flattened.

The front page of TO BHMA on February 22, 1968, captured the horror:

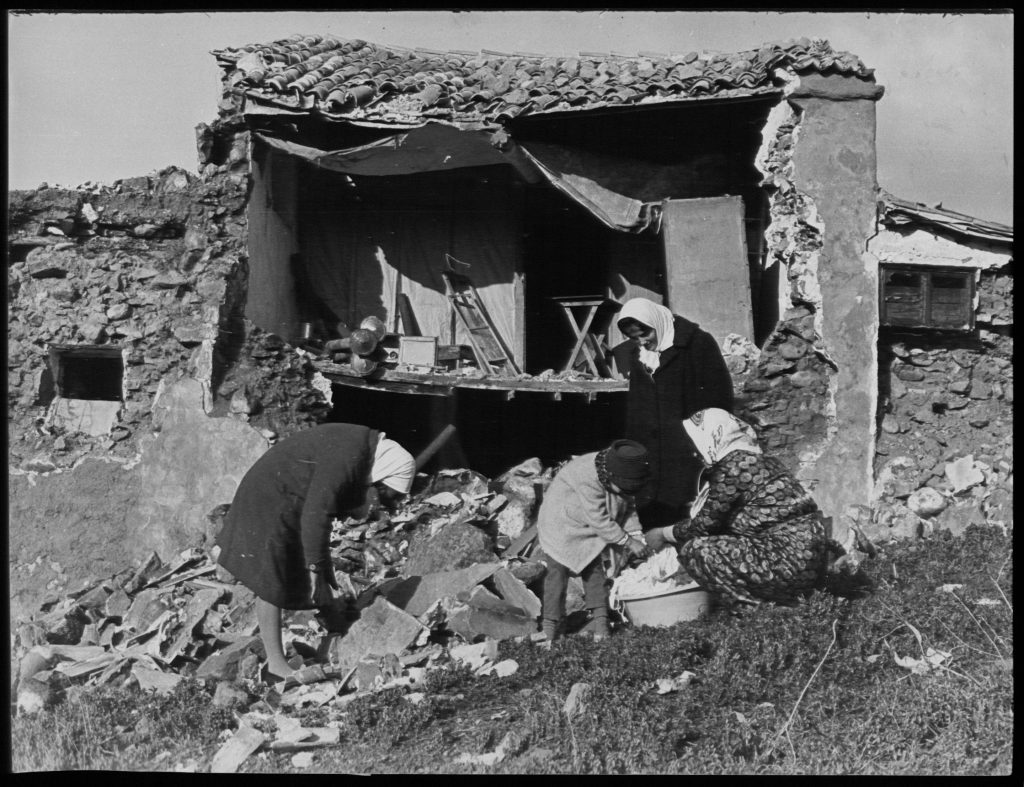

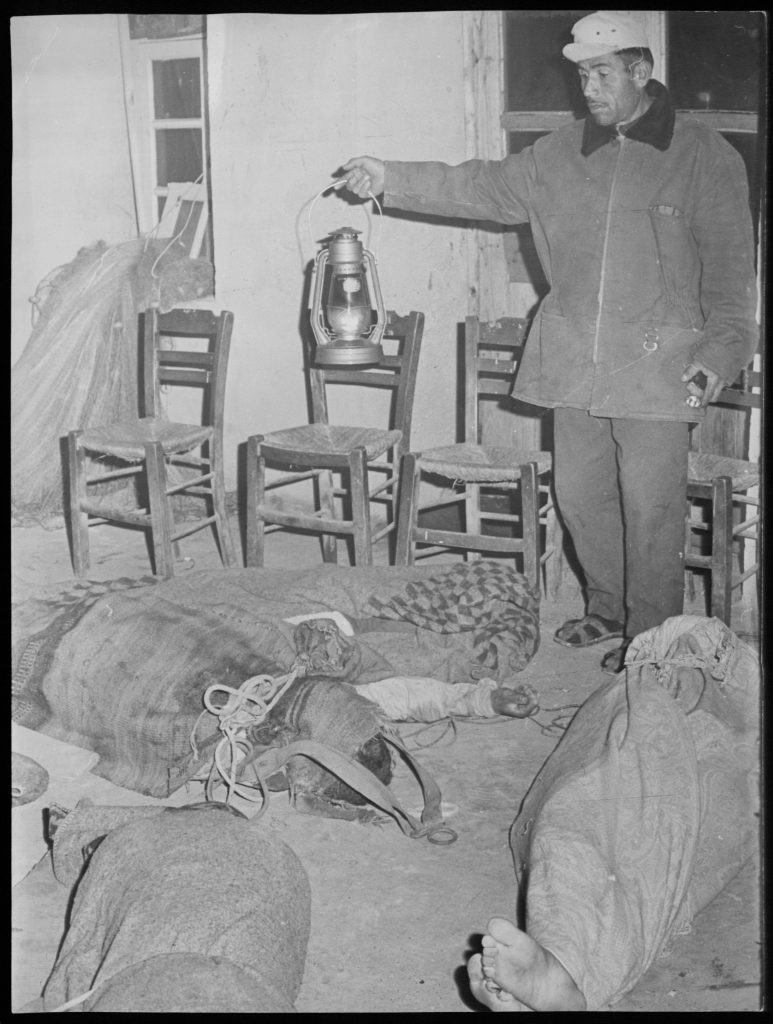

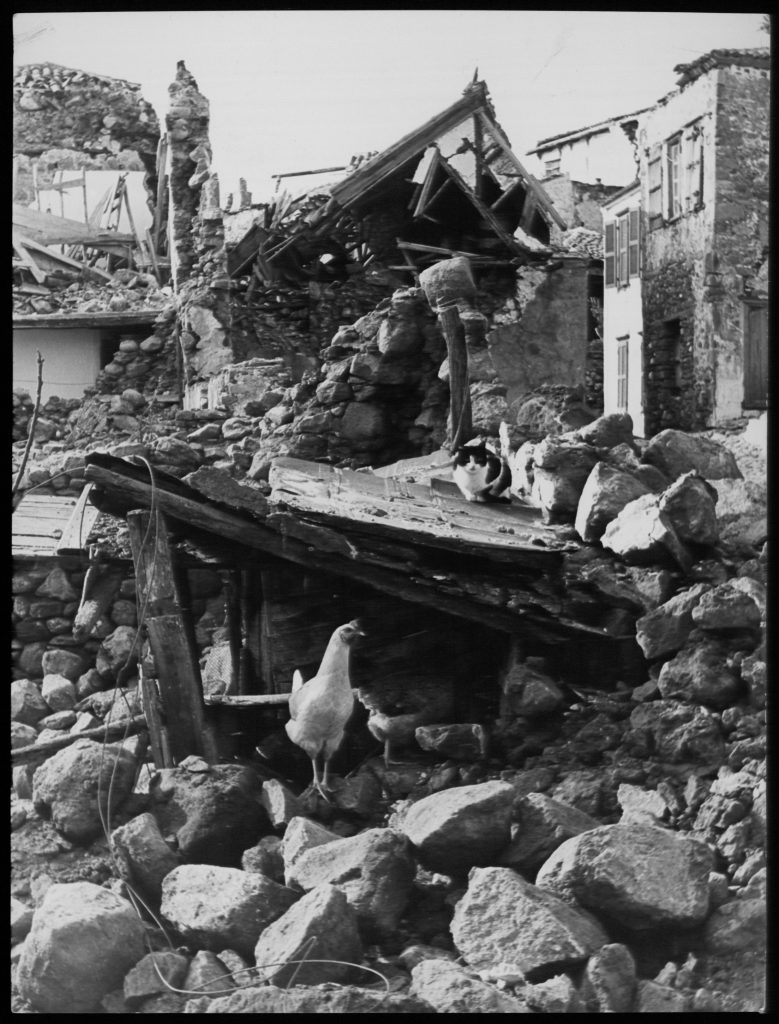

“These first photographs from Agios Efstratios show the complete destruction caused by the violent earthquake two days ago. Nothing remains standing. Everything has collapsed, and the islanders move dazed among the ruins, still unable to comprehend the disaster that has befallen them.”

Broken Lives

In the aftermath of the quake, the TO BHMA correspondent highlighted two heart-wrenching stories—stories that defined the human cost of this catastrophe.

Among the ruins sat G.M., a 45-year-old mother. In mere seconds, her world was shattered. Her two children, A. (15) and P. (7), perished under the crumbled walls of their home. She sat alone, numb, repeating one haunting plea:

“Take me away from this cursed island. Take me away from my children’s grave.”

But tragedy did not stop there. An eight-year-old boy, also G.M., had been the cherished son of a young couple. Now, orphaned by the quake, he faced an uncertain future in an orphanage. The Fleet Commander of the Northern Aegean, Captain Marinos, took the boy aboard his ship—one final journey to Thessaloniki’s Paphio Orphanage.

In the days that followed, the official narrative highlighted swift governmental intervention. Headlines spoke of “immediate and effective” support from the “National Government.” Yet, behind this façade lay a darker truth.

This was February 1968. The so-called National Government was the brutal military junta that had seized power in April 1967. Through ruthless censorship and oppression, it tightly controlled the press, shaping stories to fit its narrative.

Plans were announced to rebuild Agios Efstratios—a “modern, new” settlement. But what followed was far from a fresh start.

Anna and Despina Kapela, two islanders, remembered the days after the quake with bitterness:

“Not all houses fell. But they came with bulldozers and tore everything down. The ones who ruined them were the authorities, not the quake. There were houses untouched, perfectly fine. But they left nothing. Bulldozers cleared it all.”

Despina’s newly built three-story home had survived with minimal damage. Yet, under threat and pressure, she was forced to order its demolition:

“They told us if we didn’t knock it down ourselves, we’d have to repair it at our own expense. How could we afford that? We were poor. We had no voice. If you spoke up, you risked exile. The fear was overwhelming.”

Eventually, new houses were built. But not on suitable ground. And not as gifts. Under the watchful eye of junta Vice President Stylianos Pattakos, homes were distributed by a raffle.

Giannis Xemantilotos, another resident, recalled the bitter disappointment: “They gave us a slip of paper with a number and a sector. We opened the doors to find four bare walls. No cupboards, no shelves—nothing.”

And then came the final blow:

“Months later, the bank sent notices: ‘You owe this amount. Pay, or we’ll seize your property.’ These homes were supposed to be donations. But we paid. And we paid dearly—250,000 drachmas. Enough to buy a luxury apartment in Athens. Our so-called friends, the dictators, robbed us.”

But the earthquake stole more than lives and homes. Elisabeth Spyridonidi-Zerva, a lifelong resident, mourned a deeper loss:

“It’s as if a magic wand wiped everything away. Our traditions, our history—all vanished. The lively gatherings, the festivals at Saint Irene’s chapel, the simple joy of sharing a coffee with neighbors. All gone.”

In the aftermath, the islanders became strangers in their own land. Isolated. Disconnected. A community’s spirit, crushed under the weight of rubble and repression.

Long before the earthquake, Agios Efstratios had been a place of suffering. A remote outpost, cut off after the Asia Minor Catastrophe, it became a prison for political dissidents. From 1928 to 1963, thousands were exiled here—more than double the local population at times. Their lives were hard. The land offered little. The sea was unforgiving.

The earthquake of 1968 did not just bring destruction. It became the final chapter in a long history of hardship, silencing the island’s vibrant past, forcing a future dictated by fear and control.

Agios Efstratios was never the same again.