The assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE—known as the Ides of March—remains one of history’s most infamous political murders. Stabbed 23 times by a group of senators led by Brutus and Cassius, his violent death marked the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. While the event is remembered as a turning point in Roman history, its deeper roots in Greek philosophy, prophecy, and politics reveal how Greece shaped both Caesar’s fate and his legacy.

“Beware the Ides of March”: A Greek Influence on Julius Caesar’s Fate

The phrase “Beware the Ides of March” comes from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, where a soothsayer warns the Roman general of impending doom. In the Roman calendar, the Ides referred to the 15th day of March, May, July, and October, but after 44 BCE, the date became synonymous with betrayal. While the warning is often thought of as a Roman superstition, it has strong connections to Greek prophetic traditions.

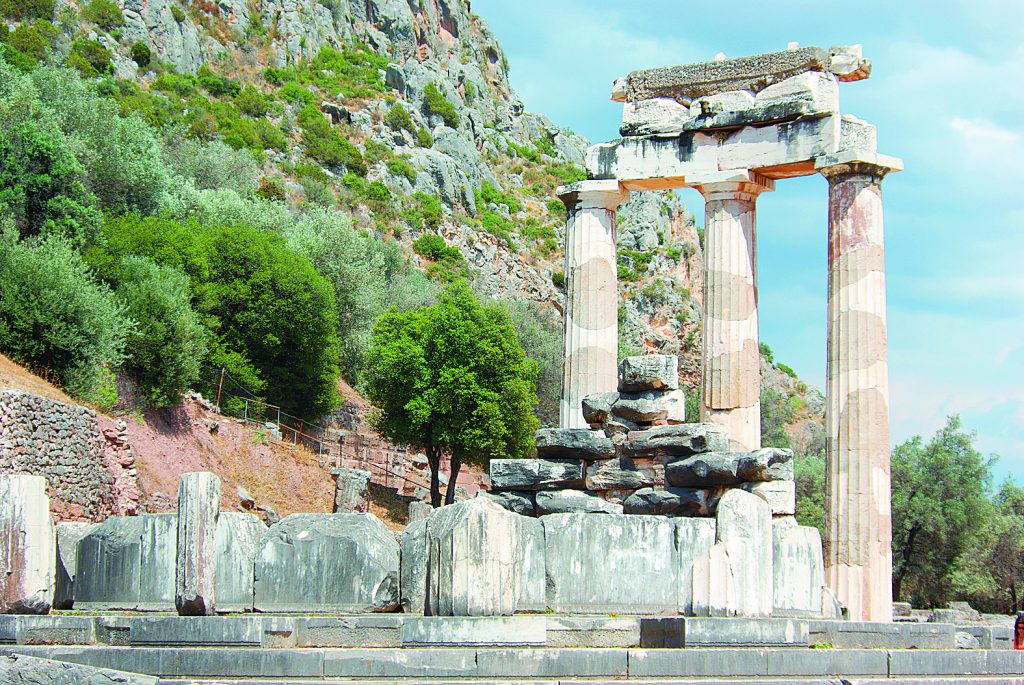

The Greeks, long before the Romans, had a deep belief in fate, often turning to oracles such as the one at Delphi for guidance on political and military decisions. Greek seers, like the Pythia at Delphi, had influenced countless leaders, and Romans—including Caesar—were deeply immersed in these traditions. Although there is no direct evidence that Caesar personally consulted Greek oracles, his belief in omens and fate was consistent with Roman reliance on Greek divination (Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus, 14.3-4).

Beyond prophecy, Greek tragedy played a role in shaping how people understood Caesar’s fall. In plays like Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex“, fate is an unavoidable force that dooms even the most powerful leaders. While Caesar’s assassination was a political act, later interpretations, particularly in literature, have drawn connections between his fate and the themes of Greek tragedy (Aristotle, Poetics, 1452b-1453b).

Delphi Archaeological site and location of the oracle.

Brutus the Betrayer: Inspired by Greek Ideals?

One of the most significant figures in Caesar’s assassination was Marcus Junius Brutus, who may have viewed his actions through the lens of Greek tyrannicide. Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who assassinated the Athenian ruler Hipparchus in 514 BCE, became symbols of democracy’s struggle against tyranny, a legacy that likely influenced Roman political thought (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 6.54–6.59; Herodotus, Histories, 5.55–5.57).

Brutus was heavily influenced by Greek Stoic philosophy, particularly the works of Cato the Younger and Cicero, which emphasized the dangers of unchecked power (Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 6–7, 36). Cato, a major Stoic thinker, was a leading opponent of Caesar, and Brutus followed his philosophy of resistance to tyranny (Seneca, De Providentia, 2.9). Cicero, in his Letters to Atticus (14.1–2), also references Brutus’ adherence to Stoic ideals in justifying his political actions.

Brutus had studied in Athens, where he immersed himself in Greek political thought, particularly the works of Aristotle and Plato, which warned of the dangers of absolute power. Though he admired Plato’s belief that the best rulers are philosopher-kings, he feared that Caesar was moving away from the ideals of the Republic and toward dictatorship. Inspired by the Greeks’ long-standing resistance to tyranny, Brutus saw the assassination as not just a political act but a moral duty—one that would restore Rome’s republican values.

However, much like in Greek tragedy, fate had other plans. Rather than saving the Republic, Brutus’ actions led to chaos, civil war, and ultimately the rise of Augustus (Octavian), who became Rome’s first emperor, solidifying the very kind of rule Brutus had tried to prevent. His attempt to emulate Greek ideals of democracy ended up accelerating Rome’s transition from a republic to an empire.

Caesar’s Love for Greece and His Political Legacy in the Region

While Brutus may have justified his actions using Greek ideals, Caesar himself was a great admirer of Greek culture, philosophy, and governance. He studied in Rhodes, where he was trained in oratory by Apollonius Molon, one of the most famous Greek teachers of rhetoric (Plutarch, Life of Caesar, 4). While Athens had supported Pompey during the Roman Civil War, there is no record of Caesar punishing the city severely, and his respect for Greek culture was evident in his engagement with Greek intellectuals.

epa000303635 A general view of Julius Caesar Hall of Campidoglio Palace, Rome’s City Hall, on Friday 29 October 2004 during the official speeches prior the signing ceremony of the European Constitutional Treaty in the Baroque Horatii and Curiatii Hall of the same palace, the place where on 25 March 1957 two treaties were signed that gave existence to the European Economic Community (EEC) and to European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom): the Treaties of Rome. Rome’s Mayor valter Veltroni welcomed the 25 official delegations of EU countries saying that “a great part of the dream of founder fathers of Europe today comes true”. EPA/GIUSEPPE GIGLIA

Even after his death, Caesar’s legacy continued to shape Greece. When civil war broke out between Mark Antony and Octavian, many Greek cities sided with Antony, believing he was the rightful heir to Caesar’s rule. The final battle of that conflict, the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, took place in Macedonia, further linking Greece to the power struggles that followed Caesar’s assassination (Appian, Civil Wars, 4.105-138). Ultimately, his death paved the way for Augustus to become Rome’s first emperor, formally bringing Greece under imperial rule and solidifying its role within the Roman Empire.

The Ides of March – A Lesson from History

Julius Caesar’s assassination still resonates today as a lesson in political betrayal, power struggles, and the fragility of democracy. The conspirators believed they were acting in defense of the Republic, but their actions led to the very thing they feared most: the rise of an all-powerful emperor. In many ways, the Ides of March was not the triumph of democracy but its undoing.

The influence of Greek thought, philosophy, and prophecy on this event shows how interconnected ancient civilizations were. From the oracles that shaped political decisions to the democratic ideals that inspired Brutus, Greek culture played an integral role in the downfall of Rome’s most famous leader. The phrase “Beware the Ides of March” remains a warning not just against political betrayal but against the unexpected turns of fate, a concept the Greeks understood all too well.