On February 19, 1962, the world lost one of its most remarkable scientists—Dr. George Papanicolaou. The pioneer behind one of modern medicine’s most powerful tools for women’s health: the Pap smear test. Known globally as the Pap test, this simple yet revolutionary screening method has saved countless lives by detecting cervical cancer early.

The following day, The Vima published an Associated Press telegram from Miami:

“Dr. George Papanicolaou, renowned for the cancer diagnostic method bearing his name, passed away today at the age of 79, after a heart attack. In his honor, the Miami Cancer Research Institute has been renamed the Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Papanicolaou first arrived in the United States in 1913. He earned a degree in zoology from the University of Munich and became a U.S. citizen in 1927.”

But the road to this recognition was anything but smooth.

A Relentless Pursuit of Knowledge

From a young age, George Papanicolaou was driven by one purpose: to serve science. After completing his medical degree in Greece, he defied his father—a respected doctor and politician—by leaving for Germany to study biology and zoology.

His journey took him to the Oceanographic Institute in Monaco and the battlefields of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), where he served as a physician. But his true calling lay beyond.

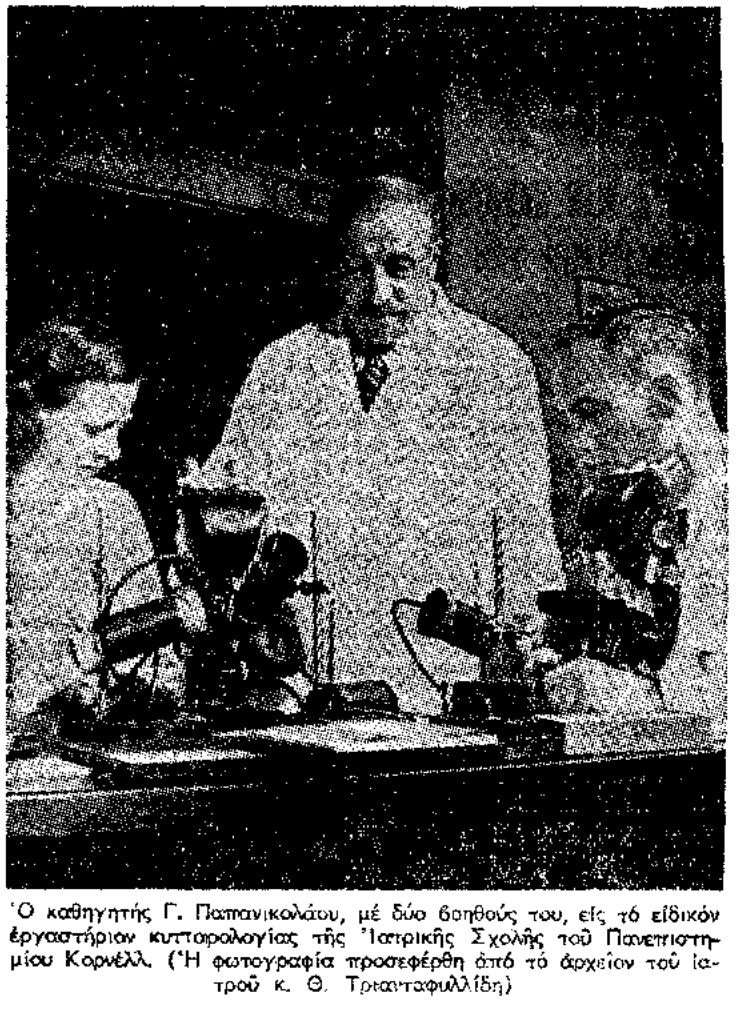

Professor G. Papanicolaou, with two assistants

Chasing the American Dream

In 1913, with little more than hope and ambition, Papanicolaou and his wife, Mache Androgenous, arrived in New York City. The early days were harsh.

“Mache sewed buttons for a living, while George sold carpets and played the violin—he was an amateur musician—in nightclubs to make ends meet,” recalled Dr. Neda Voutsa Perdiki, a close collaborator.

It took a year before Papanicolaou finally secured a position as an assistant researcher at New York Hospital, part of Cornell University, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

An Obsession with Discovery

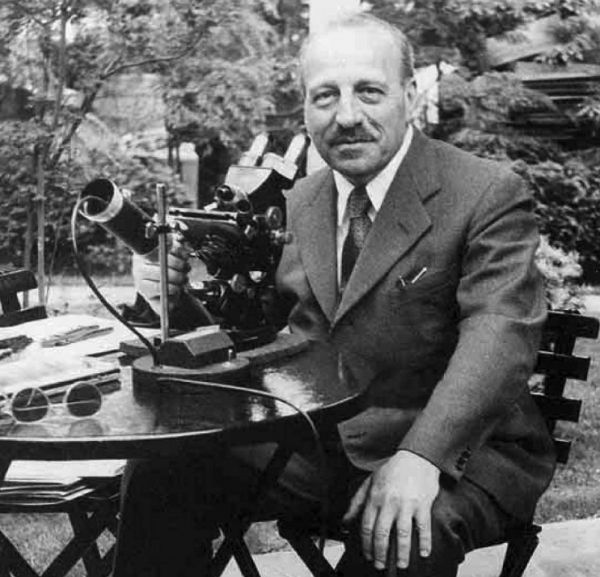

Dr. Papanicolaou’s dedication to research was unparalleled. He worked tirelessly, even using the hour-long drive home to Long Island as time to pore over notes and data.

“You have a backseat driver’s license!” his wife would joke.

Not even Easter celebrations could pull him away from his microscope. On one occasion, his family had to set up his microscope in the garden during a holiday gathering—research always came first.

The Discovery That Changed the World

It all began with simple experiments. Using vaginal smears from his wife and later from women working at the Women’s Hospital—whom he paid for their participation—Papanicolaou made a groundbreaking observation: among normal cells, he identified malignant ones.

“It was the most thrilling moment of my life,” he later said.

But the scientific world wasn’t ready. When he presented his findings in 1923, his peers dismissed him, some mockingly calling him “the Greek storyteller.”

Triumph Over Doubt

For nearly two decades, his research remained in the shadows. It wasn’t until 1939 that the scientific community began to acknowledge the significance of his work, as a new field—Clinical Cytology—began to take shape.

By 1943, his persistence paid off. The Pap smear test was officially recognized, with the publication of his landmark work “The Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Smear.” Backed by top medical schools like Harvard, Boston, and New York, the Pap test became a standard part of women’s healthcare around the world.

A Legacy of Purpose

When asked about his life’s goals, Papanicolaou said:

“My ideal is not to become rich, nor to live happily, but to work, to act, to create—

to do something worthy of a strong and moral human being.

I want to fight on the front lines—

to either fall with honor or carry the flag of progress forward into the future.”

And that’s exactly what he did.