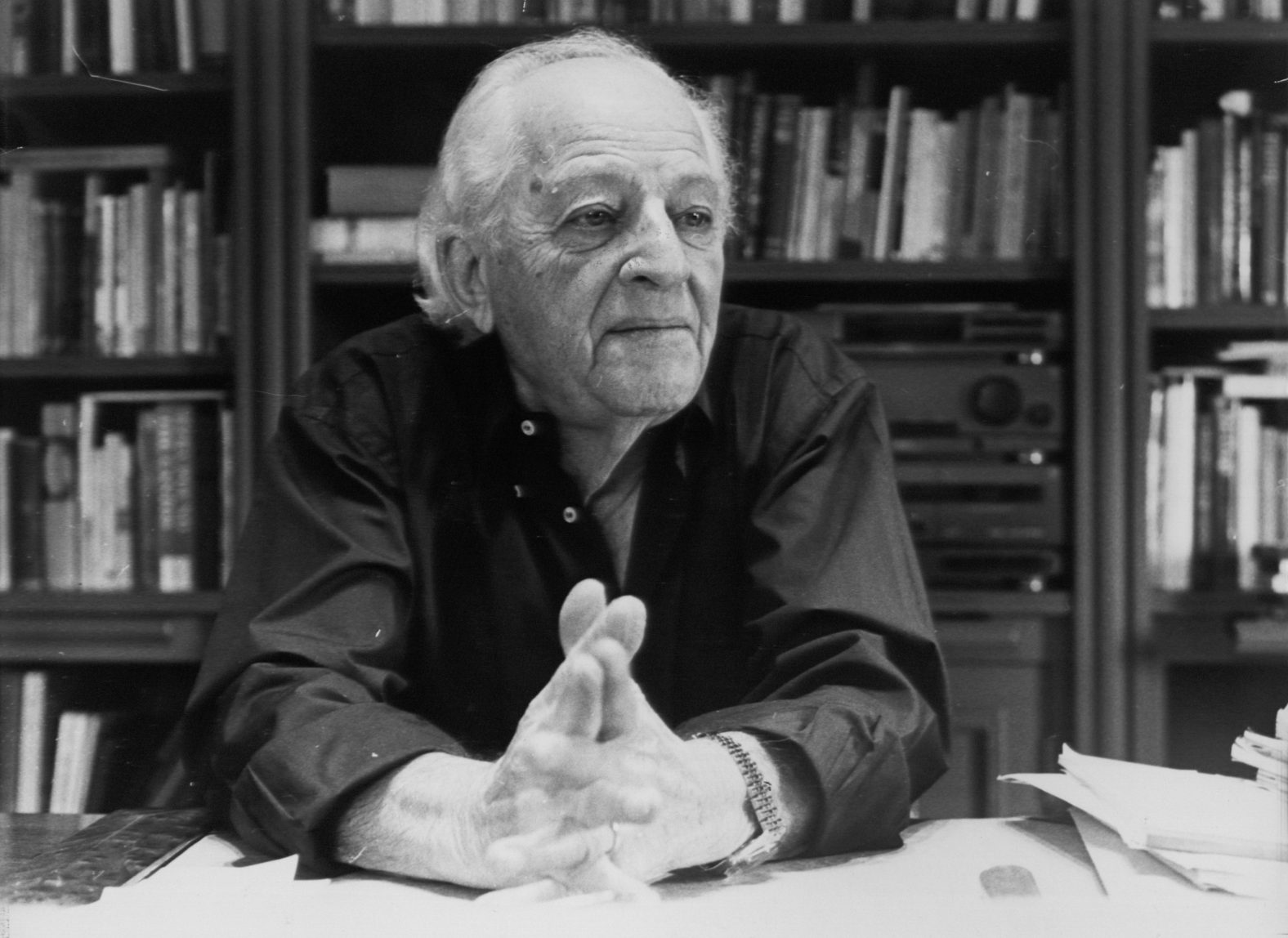

On March 31, 2008, at the age of 97, legendary American filmmaker Jules Dassin passed away, leaving behind a cinematic legacy that spanned over two decades. With more than twenty films to his name, many of them critically acclaimed, Dassin secured his place in film history.

His 1955 masterpiece Rififi won the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival, while Never on Sunday became an international sensation, earning multiple Academy Award nominations, including Best Actress, Best Screenplay, and Best Director. Ultimately, the film won the Oscar for Best Original Song for “Ta Pedia Tou Pirea” (“The Children of Piraeus”), composed by the great Manos Hadjidakis.

But Dassin was more than a filmmaker—he was a visionary, a provocateur, and a man deeply entwined with Greece, a country he made his home after marrying actress and politician Melina Mercouri. His artistic footprint extended beyond film into theater, where he continued to challenge and inspire.

“Talent, But No Theater”

In November 1984, Dassin sat down for an interview with Tachydromos magazine, where he spoke candidly about Greek culture and the struggles of artists in a country with such a rich history yet limited resources.

“There is so much talent in Greece,” he remarked, “but in Athens, there is no real theater. How is it possible that the country that gave birth to theater has no thriving theatrical scene? I see poets, visual artists, actors—people engaged in a constant battle for survival.”

He lamented the financial constraints that forced small productions to limit their casts to just a few actors. “It’s the pressure of money,” he said. “Greece is too poor for its immense cultural heritage. Ancient monuments stand in need of preservation, yet the people to care for them are scarce. And no one seems interested in reconciling these contradictions.”

Ancient Glory and Modern Realities

Dassin pointed to a stark example—the Epidaurus Theater, one of Greece’s most treasured ancient sites. “If you visit Epidaurus, you’ll see modern houses and neon lights creeping into the landscape. The new constructions destroy the harmony of the environment.”

He acknowledged Greece’s pressing needs—schools, roads, hospitals—but argued that culture should not be sacrificed in the name of economic survival. “People always say, ‘Please! We have bigger problems than culture!’ But I believe that a thriving cultural life would actually lead to more roads, more hospitals, and more schools. These things are not separate. The Bible itself says: ‘Man shall not live by bread alone.’”

The Fight for the Parthenon Marbles

Dassin was a passionate advocate for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, taken by Lord Elgin and housed in the British Museum. “Every day, newspapers in England and around the world write about them. More and more British citizens—archaeologists, politicians, professors—even members of Thatcher’s own government have admitted that what happened to Greece was unjust.”

Yet, he expressed frustration at the apathy within Greece itself. “Here, people dismiss it as ‘Melina’s cause.’ That infuriates me. In Japan, articles are written daily about the Marbles. And here? Indifference. A lack of faith. In Greece, what’s missing is friendship. And without friendship, one cannot see things clearly.”

The Oscars and the Illusions of Cinema

Back in December 1979, as he was finishing his film Circle of Two, Dassin gave another interview to Tachydromos, where he reflected on the fleeting trends in cinema and the significance—or lack thereof—of awards.

“Film has its fads. Westerns dominate for a while, then horror, then disaster films, then hyper-violent movies. I never followed these trends. If I made a love story now, it’s because I wanted to, not because I was chasing awards.”

When asked about the Academy Awards, he was blunt: “Charlie Chaplin and Greta Garbo never won Oscars—doesn’t that tell you something about their true value? I know how awards are given. Even my own award-winning films, Rififi and Never on Sunday, had their flaws. Of course, if they gave me another Oscar today, I wouldn’t be upset…” he added with a wry smile.

Bildnummer: 60047602 Datum: 09.07.1961 Copyright: imago/United Archives International

9 JULY 1961 DIRECTOR JULES DASSIN WITH ACTRESS MELINA MERCOURI FILMING PHEDRE IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, ENGLAND. kbdig 1961 quadrat 1960 1960 s 20th Century 60 s Actor / Actress B&W Personalities The Sixties archival archive black & white monochrome negative news old sixties PUBLICATIONxINxGERxSUIxAUTxONLY

The Nostalgia for Lost Hope

Dassin also observed a cultural phenomenon—the resurgence of interest in classic pre-war films. “People are filling theaters to watch movies from the interwar period. And this nostalgia is more than just a retro trend. It’s a desperate attempt to find the hope we lost.”

“After World War II, a new dawn seemed to rise, full of promise. But that hope died quickly, without bringing the change we expected. An idealism was defeated, and nothing came to replace it. So, we look back to those earlier, hopeful days—when we still believed in something, before we knew what the future held.”

The Outsider Who Found Home

When asked about his future, Dassin spoke with the wisdom of a man who had lived many lives. “If you had asked me in 1948 or 1950 about my plans, I could have talked for days. But now, things are different. I chose a new life, far from my roots. I changed everything. To tell you the truth, I feel like a bastard child of cinema…”

Jules Dassin was an exile, an artist, a rebel. Blacklisted in Hollywood during the McCarthy era, he found refuge in France and then in Greece, where he built a new life, shaping its cultural landscape through film and theater. Even in his final years, he remained a passionate voice for justice, art, and heritage—a man who never stopped believing in the transformative power of storytelling.

He may have felt like an outsider, but in the hearts of those who loved his films and shared his vision, Jules Dassin was truly home.