If Melina were alive today, she’d be exactly like she always was. Because her passion and her beliefs, her principles and values, were so deeply rooted in her being, and such a vital element of her driving force, they wouldn’t have changed or faded one iota. And, of course, she’d be thrilled that her vision for the return of the Parthenon Marbles has become a national cause and a political priority, which certainly wasn’t the case when she started her quest. She’d be every bit as angry, too, if she had to shoot a scene at the British Museum in front of the Marbles—as she did in 1960 for Jules Dassin’s Phaedra, in which she starred alongside Anthony Perkins—and the British asked for payment to grant permission to the Greek crew. “Since when do you have to pay to film something of your own?” she’d say, even if she had nothing to do with the film herself.

Because that was the incident that spurred her on to make the Marbles’ return her life’s work and vision. And even if she hadn’t become a politician—which was almost certainly not something she was considering in 1960—she would have leveraged her international fame all the same to take the podium at the UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies in the summer of 1982, which is where she first raised the issue of a return. Because even back then, when “cultural policy” was still a somewhat vague and abstract concept, it still clearly referred to the future. “We are not naive,” she said. “The day may come when this world will create other visions, other concepts of what is proper, of what comprises a cultural patrimony and of human creativity. And we well understand that the museums cannot be emptied. But I insist on reminding you that in the case of the Acropolis marbles we are not asking for the return of a painting or a statue. We are asking for the return of a portion of a unique monument, the privileged symbol of a whole culture. I think that the time has come for these marbles to come back to the blue sky of Attica, to their natural space, to the place where they will be a structural and functional part of a unique whole.”

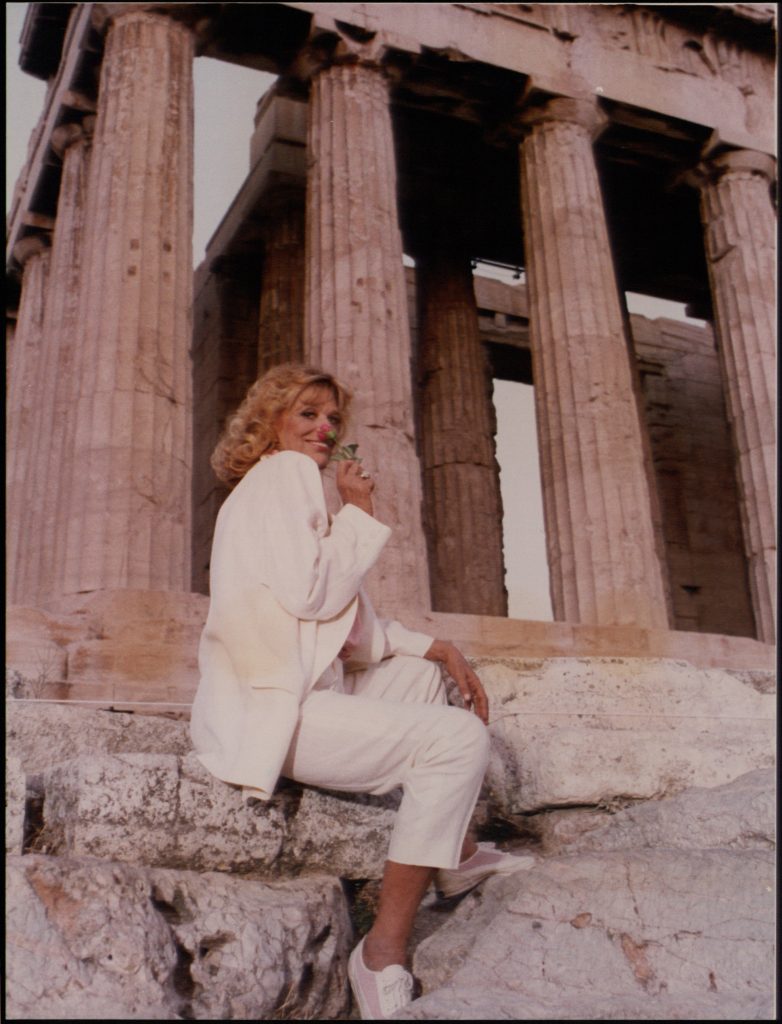

Melina was angry about the Acropolis marbles. And she didn’t mollify her anger, she didn’t try nor want to calm her ire until its source had been removed. Meaning, she would still be angry today. And as sarcastic as she always was when she was in the right and knew it, as she was in April 1983 on her first trip to London as Greek Minister of Culture. The campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles has just begun, and of course the British expected her to raise the issue in no uncertain terms. The Director of the British Museum at the time, Sir David Wilson, was present at the official dinner at the Institute of Contemporary Art, as were many dignitaries both British and Greek. Melina gave her speech, but made no reference whatsoever to the “Marbles”. Everyone sighed with relief. And they made the mistake of applauding her warmly.

When the guests had sat down, Melina stood up again to thank them. And (supposedly) to apologize for her “bad English”. “I heard it and was reminded of what Dylan Thomas said of a British broadcaster: “He speaks as if he had Marbles in his mouth.”

Melina never minced her words. And she wouldn’t do so now, if she were still alive, because it was part of her quintessence: it made her who she was. If she met the current Director of the British Museum, she’d say just what she said to Sir David Wilson, and in just the same way, with a wag of her finger. “I want my Marbles back!” she told him, and when he replied “You want your marbles, and others want their marbles,” she was furious. “They are part of a monument,” she retorted. “They are torn down. Are you saying there are many Parthenons in the world?” she asked him angrily.

She would go to conferences and talk about Lord Elgin’s theft wherever she could. She would never soften her words, always choosing “theft” and repeating it many times over, having first promised to keep her cool. Which is what she did in the speech she gave to the Oxford Union in 1986. On that occasion, she said: “You know, it is said that we Greeks are a fervent and warm-blooded breed. Well. let me tell you something—it is true. And I am not known for being an exception. Knowing what these sculptures mean to the Greek people, it is not easy to address their having been taken from Greece dispassionately, but I shall try, I promise.

She would, of course, have been happy that one of her goals, the construction of the Acropolis Museum whose absence was an impediment then to the Marble’s return, has been achieved. In one thing only would she fail to keep her word. She once said that if, when the sculptures were returned, she had died, she would be reborn. And she was a woman of her word. In this case, she would not be able to keep it. But the fault would not be hers.