An overloaded passenger train heading toward Athens crashed headlong at 80 km an hour into a second packed train that had come to a standstill about 500 meters before the station in Derveni on the Gulf of Corinth.

With 34 dead and 125 injured, the railway accident that took place on September 30, 1968 was one of the bloodiest in Greek history.

Hundreds of thousands of people had returned to their ancestral towns and villages in the previous days to vote in the rigged referendum that was supposed to legitimize the Constitution of the Colonels’ regime.

From TO VIMA of October 1, 1968:

‘A violent collision between two trains with many dead and injured was reported at 6.25 this afternoon in Derveni on the Gulf of Corinth.

(…)

‘The two trains were traveling to Athens and were packed with passengers, most of them returning to the capital from the towns and villages where they are registered to vote.

TA NEA, 1.10.1968, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive

The fateful faint

‘One of the two trains had departed from Kyparissia at around two in the afternoon and the other from Kalamata ten minutes later. After the first train had passed through Derveni station and continued for another 200 meters or thereabouts, a sailor fainted in one of its carriages.

‘While some of the passengers provided first aid, another thought it best to pull the emergency stop. As a result, the driver stopped the train and was informed that a passenger had fainted in one of the passenger cars.

‘Because the passenger was thought to be in a somewhat critical state, it was decided to transfer him to a clinic in the Derveni area.

‘In the meantime, as all this was happening, the Kalamata train, which was running ten minutes behind on its way to Athens, approached the point in question and crashed into the stationary train car with terrifying force. The impact was terrible.

‘The two trains crashed, resulting in many of the passengers being crushed and dozens injured.’

TA NEA, 1.10.1968, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive

TA NEA writes:

‘Death staged a terrifying dance yesterday at 6:25 in the afternoon 500 meters from Derveni railway station in Corinthia.

‘The 2,000 or so passengers on two trains were struck at that precise moment as if by lightning, or as though an earthquake had occurred.

(…)

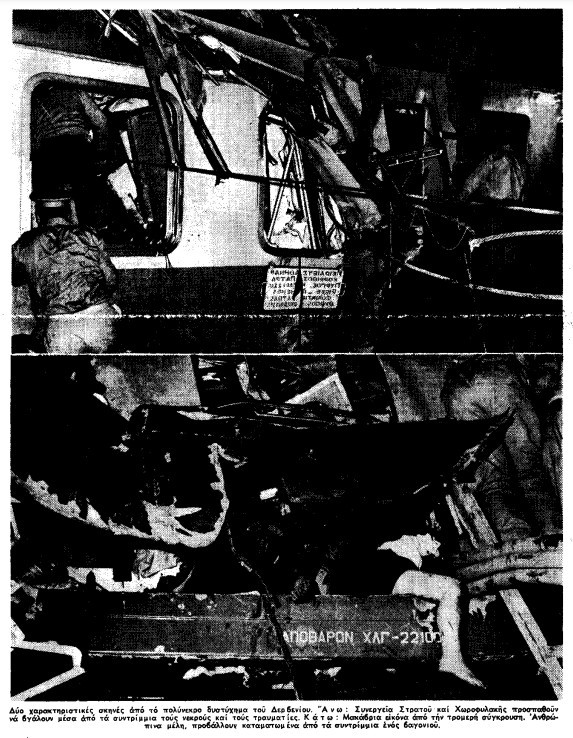

‘The dramatic effort [to recover the dead and extricate the injured] lasted for hours, while the scene of the tragic accident was floodlit by the headlights of army crews, which illuminated the mangled bodies, the limbs dangling from the wreckage, the bloody uniforms of the paramedics, the dozens of ambulance cars, the civilians, soldiers and gendarmes doing everything in their power to find the dead and injured. (…)

‘The efforts to free the living had a chilling guide: the wails of the injured and the cries of little children.

TA NEA, 1.10.1968, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive

The collision and the subsequent panic

‘After the Kyparissia-Athens train made an emergency stop: the second passenger train approached a few minutes later from the same direction as the first and along the same tracks. But there was a bend at this precise spot.

‘Meaning the driver of the second train remained unaware that the 14-car service had come to a halt just a few meters ahead of him. And did not slow down. The result? Fifteen passenger carriages smashed into the stationary cars at high speed.

‘The impact was shocking. Scenes of panic and terror followed, especially in the last three cars of the first train.

‘People were banging their heads against the windows, attempting to break them so they could escape the hell within. Cries, screaming babies, shrieks of pain, horribly disfigured faces. And panic. Which spread from carriage to carriage. A crush of bodies at the doors. Men, women and children jumping out of windows and running for their lives through the fields as though death itself was in pursuit.’

TA NEA, 1.10.1968, TO VIMA & TA NEA Historical Archive

An eye-witness account

‘One of those who survived, Nikos Kapsis, a builder, was able to say a few words about the accident:

Myself, my pregnant wife Georgia and my sister Dimitra boarded the train in Patras at 3.30.

I remember the alarm sounded for the first time between Patras station and the engine yard (Agios Georgios), and the train stopped for 15 minutes. The railwaymen got off the train and loosened the brakes.

The second time the train stopped was at Derveni. No one got off the train, and I think it stopped because a lady’s child fainted and she pulled the emergency signal.

While the train was stationary, my sister moved from the second-to-last carriage where we were sitting to the very last one.

The collision occurred a few moments later. What happened beggars description. Everyone was trying to save themselves without a thought for anyone else. I still don’t know what’s happened to my sister.

‘As the hours passed, the death toll rose and different versions began to emerge about why the first train stopped.

‘From what we know so far, the accident was caused by a passenger fainting on the train traveling from Kyparissia to Athens, which was ten minutes ahead of the Kalamata service, which was traveling on the same tracks and in the same direction. There are two versions of what would ultimately cause the tragedy.

‘- (…) An elderly woman who fainted and whose condition was considered serious by some passengers.

‘- A young child who had eaten cheese which gave him food poisoning, as a result of which his mother panicked.

(…)

‘Whatever the case may be, a passenger pulled the emergency lever for one reason or the other (…) The train driver then brought the train to a halt to see what was wrong.

‘At the same time, the passengers in one of the carriages carried the person with the problem off the train, so they could be taken to a clinic in Derveni.

(…)

‘The risk of collision was made even greater by the location at which Train 304 came to a stop. It was a point which offered no visibility from the rear. And it would not take long for Fate to strike.

‘The second train (Service 306), which was traveling from Kalamata to Athens driven by Eleftherios Kourouniotis, caught up with the preceding service and found itself bearing down on the stationary train at speed.

‘It smashed with such force into the stationary train, its engine split the last two cars in two, destroying them utterly. The whole area was covered in blood and flesh. Death took 34 people into its embrace that day.

‘The surrounding area darkened with the desperate cries of people trapped in the wreckage of the two carriages. The scene was so terrifying, many passengers who had not suffered any physical harm could not bear it and started running toward the mountainside.

TA NEA, 2.10.1968, Historical Archive

No red flags

(…)

‘Both the driver of the first train and its conductor, A.L. Kitsios, knew that the second train was on its way ten minutes behind them. So why (…) did the guards not deploy red flags or red lights to warn its driver that their service had stopped?

‘As became clear later, valuable time was lost and when the crew of the stationary train did finally get round to attempting to place warning signs at a sufficient distance to allow the moving train to stop in time, it was already too late.’

As reported in TO VIMA of October 4, 1968, the railway workers’ union issued a statement to the effect that the railwaymen ‘ran red flag in hand to ensure the safety of the stationary train.

‘However, due to its great length, they had to run the full length of the train, which was in excess of 200 meters, before they could seek to secure a safe distance. And although the lead runner managed a further 150 meters before the collision, this was an insufficient distance to prevent the accident.’