In the heart of Bethesda, Maryland, nestled among the leafy streets, lies a neighborhood affectionately known in Greek as “chorio,” or village, to its inhabitants. Here, three families share more than just a residential block; they share a rich heritage of Greek ancestry and a legacy of public service spanning generations.

At the center of this story is the Manatos family, whose roots trace back to the rugged mountains of the island of Crete, extend to the coal mines of Wyoming and culminate in the corridors of power in Washington, DC.

A closer look at this extensive family history reveals more than a mere testament to the enduring spirit of the Greek-American community. It provides a glimpse into the evolution of the rich tapestry of the Greek diaspora.

This year, the family’s lobbying firm, Manatos & Manatos, celebrated its 40th anniversary. The memorabilia adorning the walls of their office reveal part of this history. Among these pieces are presidential pens used to sign landmark pieces of legislation such as the Civil Rights Act, Medicare, arms control treaties, and voting rights laws.

(L-R) Mike Manatos, Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi, Archbishop Elpidophoros, and Andy Manatos at the Celebration of 40 years of Manatos& Manatos. Credit: Manatos & Manatos.

“My grandfather (Mike Manatos Sr.) was involved in lobbying to get that passed and then received a pen that signed this bill,” explains Mike Manatos Jr. “Growing up and seeing them be a part of making that kind of major change affecting millions of lives was really inspirational.”

Reclaiming Identity in the New World

The story begins with a young Cretan whose journey from Greece to America mirrors the quintessential immigrant narrative. When Nikos Manatakis arrived on American shores with little more than dreams, little did he know that he was destined to carve out a path that would leave a mark on the landscape of Greek-American relations.

Nikos Manatakis set foot on Ellis Island in 1910, seeking a new beginning in the land of opportunity. But his journey from the island of Crete to the United States marked more than just a physical relocation; it signaled a reclaiming of his identity.

Nikos Manatakis in Chania Crete, circa 1910. Credit: Manatos & Manatos

This was because Nikos Manatakis, later known as Nikos Manatos, made a deliberate choice to shed the imposed “akis” suffix from his surname, a relic of the Ottoman occupation of Crete. His decision was not a gesture of assimilation but a silent protest against centuries of foreign rule.

But at that time Nikos likely didn’t realize this decision would lead his descendants into a bureaucratic tangle with the Greek state. Almost a hundred years later, his great-grandson, Mike Manatos Jr., now the President of the Manatos & Manatos lobby firm in Washington, is working to establish that his family name originates from Manatakis, aiming to secure Greek citizenship.

“Our obstacle is that the Greek government has confirmed that Nikos Manatakis left Chania in Crete in 1910 for the United States,” Mike Manatos Jr. explains. “However, when he arrived, he changed the name. So, I need to find some kind of legal document that shows that Nikos Manatakis is Nikos Manatos.”

Mike Manatos Jr. is not alone in his endeavor. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Greek consular services in the U.S. have witnessed a surge in interest among Americans with Greek ancestry who seek to reclaim their family’s lost Greek citizenship.

However, many individuals come from families with scant documentation for one or more generations and encounter similar obstacles as Mike Manatos Jr. due to surname changes upon immigration to America.

“Ellis Island officials were infamous for changing family names. For example, General Papas, the head of the U.S. Army Forces, his name is spelled Poppas because the person in Ellis Island just wrote it that way,” Mike Jr. recounts. “So, some did do it for a fresh start, but others for assimilation purposes because they didn’t want to be named Papadakis.”

Today, the Manatos family has called Washington home for almost 80 years. But if Mike Jr. wants to find the documents of his great-grandfather, he might have to look further afield.

Amidst adversity, the first generation of the Manatos family found resilience and camaraderie in unexpected places in the new world. Wyoming, with its stark landscapes and sparse population, became an unlikely home for Greek immigrants seeking a foothold in the American West.

Finding a Home in the American West

There is a good explanation for that. When the Cretans arrived at the Port of New York, they were offered jobs to build a railroad across the country. So, many of these people decided to settle down and start families in Utah and Wyoming because the railroad jobs led them there.

It was in the little town of Rock Springs that Nikos Manatakis toiled in the coal mines, enduring hardship to secure a better future for his descendants. Upon his arrival, there were about 200 Greek families in the town. Twenty years later, one-third of the heads of households had died in the mines.

“It was brutal. Nikos Matatakis would see sunlight only on the weekends because he would arrive at the mines in the morning. It was dark. He would go in. It was pitch black. He would come out at night. It was dark,” recounts Mike Manatos Jr. “And that’s how they lived to make money and start their family here in America.”

Mike Jr. heard the story from his father, Andy Manatos, who shared it as a reminder of the remarkable sacrifices made by that generation, so that their kids and their grandkids could get a better life.

“There were a lot of different family stories, but most importantly my father would emphasize that although they had nothing, they felt like they had everything. They truly appreciated the little they had and the great opportunity they had been given.”

Prejudice Beneath the Surface of Diversity

The Greek way of life, centered on family, trust, and pride, found a natural home in the heartland of America, where communities thrived on strong familial ties and faith-based values.

Rock Springs, with its mix of ethnicities—Greek, Chinese, German, Russian—was a surprising blend of cultures. Nikos Manatakis’s brother’s pool hall became a hub where people from Greek, Chinese, German, and Russian communities gathered.

But beneath the surface of this diversity lay the harsh reality of prejudice. Discrimination reared its ugly head in various forms, from the destruction of Greek-owned businesses like the pool hall to housing policies that kept certain neighborhoods off-limits, even decades later, when Nikos Manatakis son, Mike Manatos Sr., arrived in the nation’s capital.

Andy Manatos, the grandson of Nikos Manatakis, remembers stories passed down through the years. He recalls how in some small towns, signs hung in windows declaring, “no N-word and Greeks allowed.” Yet, amid these challenges, Andy sees a quiet strength in his grandfather, a man of few words but deep wisdom.

“A lot of those old Greeks didn’t have much formal education, but they had a lot of smarts,” Andy reflects. “My grandfather used to say to my dad (Mike Sr.) and me, ‘I can’t leave you a lot of money, but I can leave you a good name.’”

Indeed, this good name proved to be more valuable than riches. When Mike Manatos Sr., then a teenager, found himself on the cusp of a life-altering opportunity, it was his family’s reputation that paved the way. A United States Senator from Wyoming sought a young man to join his office in Washington, DC, and Mike’s name was put forward.

Mike Manatos Sr., brimming with youthful energy yet with a hint of innocence, was standing at a crossroads. On one side, lay a life-altering opportunity. On the other, his commitment to his Greek pals and their basketball team, which was gunning for a championship.

Facing such a dilemma, he initially brushed off the Senator’s offer, citing his loyalty to the team. But whoever has met a Greek mother could easily anticipate that he stood a better chance to win a basketball championship in Washington DC than in Wyoming.

As Andy fondly recalls, “dad brought it up at dinner, and before he knew it, he was on a train bound for Washington. It wasn’t his big dream, but his parents ensured he did the right thing.”

While life unexpectedly led him to Washington, it was the ties to home that guided him toward finding love. Cretans are notorious for their tight-knit communities, and young immigrants like Mike Manatos Sr. often found themselves spending significant time in nearby Salt Lake City, where a sizable community of their compatriots resided.

It was at one of these gatherings that he met Dorothy Varanakis, the love of his life and future wife, who, like him, was a first-generation immigrant in Utah.

The Pressure to Fit In

Mike Sr. arrived in Washington, D.C. as a young man, lacking a college education and feeling intimidated by the city’s grandeur. On his first day, he only made it to the Capitol building before retreating to his hotel room, overwhelmed by the new surroundings.

“My grandparents came in 1937. My father (Andy Manatos) was a little boy. And my grandmother was very intimidated. She came from the state of Wyoming and Utah. So being in Washington, DC, was a big deal,” Mike Manatos Jr. said.

Yet, the specter of prejudice and the relentless pressure to conform lingered. Years later, Andy Manatos found himself pondering how his family had lost their Greek language. He often revisited a poignant memory shared by his mother, Dorothy.

“She was sitting in a park. I touched her shoe, and said, ‘papoutsi,’ which means shoe in Greek. A non-ethnic woman who overheard turned to my 23-year-old mother and said, ‘you are in America, speak English,’” Andy narrated. “And just like that it was lost. They ceased speaking Greek because they didn’t want their children to feel like they didn’t belong. And that’s truly heartbreaking.”

This fear of being an outlier haunted Andy’s parents for many years. As Andy grew up in Washington, his friends would sometimes greet him with a casual “hey Greek.” However, for his parents, who vividly remembered hearing the hurtful slur “filthy Greek” as children, the initial reaction was one of offense.

“They thought, ‘oh, these people are trying to insult you,’ assuming it carried the same negative connotations,” Andy reflected. “But, as you know, by that time, it was a badge of honor. Greek culture was esteemed, so being called Greek was no longer derogatory.”

In the end, neither fear nor prejudice hindered the ambitions of Andy’s father. Mike Manatos Sr. swiftly ascended to the position of chief of staff for a United States Senator. And when Senators Kennedy and Johnson were elected President and Vice President and went to the White House, the one person they selected to go with them and handle the United States Senate was Mike Manatos Sr.

35th U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Mike Manatos Sr.

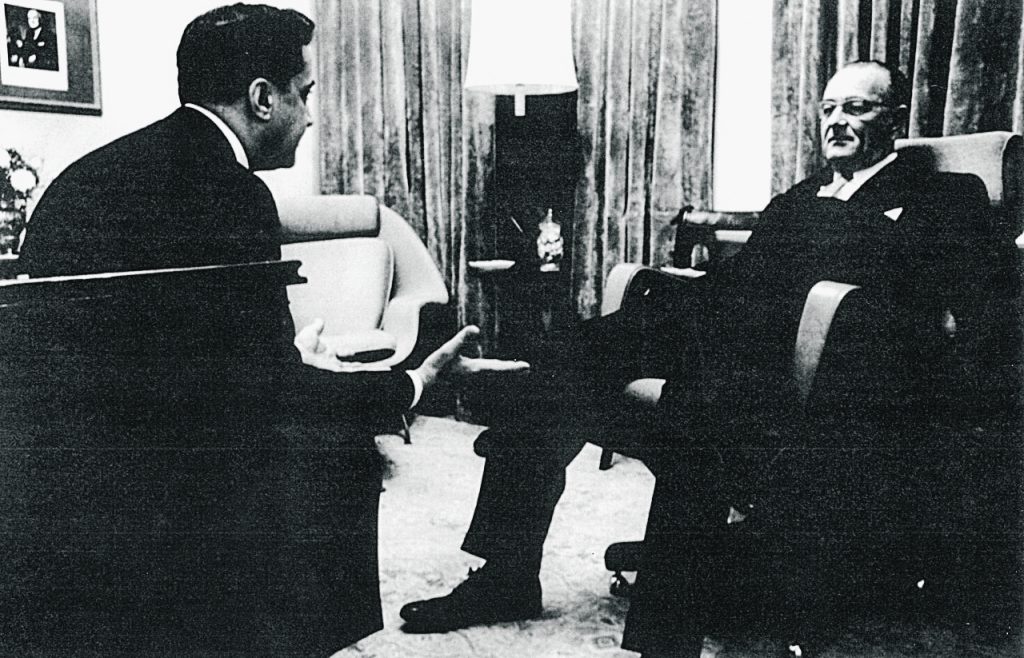

Mike Manatos Sr. with the 36th U.S. President, Lyndon B. Johnson.

His grandson, Mike Jr., reflects on this a remarkable journey. “In 20 years, he rose from a person who knew nothing about Washington and the government, so intimidated by it, to become this well-respected, well-trusted person who knew Congress so well.”

Letter from a President

In the decades following Nikos Manatakis’ arrival in the New World, Greeks in America made significant strides in improving their educational, financial, and professional status. Yet, despite these advancements, they remained ill-equipped and disorganized when it came to engaging with the highest levels of the national government.

Mike Sr. arrived in Washington at a time when the Greek community was seeking greater involvement in national politics. However, this period was marked by division, with competing groups vying for influence and even church parish affiliations being determined by political loyalties back in the homeland.

Against this backdrop of division, word began to spread about a young political staffer working in Congress who would later become the first Greek American to work in the White House. Very soon, people started reaching out to him.

Perhaps it was fate that placed Mike Manatos Sr. at the White House at precisely the right moment. Few recall the tense events of 1964 when Turkey dispatched its ships to Cyprus, prompting a stern warning from President Lyndon Johnson to avert invasion.

In the early hours of that crucial morning, Mike Sr. received a call, summoning him to the White House. “You need to come in; the president must talk to you; there’s a situation with Turkey and Cyprus,” he heard from the other end of the line.

This call must have come as a surprise. Not only did he lack substantive foreign policy experience, but his primary role involved passing bills through the Senate. Yet, the President believed that his only Greek-American staffer might offer valuable insight. Thus, Mike Sr. found himself tasked with drafting the infamous Lyndon Johnson letter that successfully deterred Turkey’s initial incursion into Cyprus.

Andy Manatos remembers that the President was severely criticized for the so-called Johnson letter with the foreign policy establishment in Washington going after him because they felt it was a big mistake.

However, the subsequent decade saw a stark reversal of fortune for Cyprus. In 1974, the Nixon administration held sway in Washington, and it was Andy Manatos turn to pick up the fight in Congress. This time, the response from the U.S. government was remarkably different, with a hands-off approach that ultimately allowed Turkey’s invasion to proceed unchecked.

“The U.S. government just did horribly,” Andy lamented. “As a matter of fact, I’m one of the few people who can verify that when the invasion began, our government reached out to the Greek junta and instructed them not to intervene against Turkey.”

Reflecting on this turn of events, Mike Manatos Jr. suggests that the Greek-American community may have become complacent over the years, lacking the sophistication and resources needed for effective engagement in governmental affairs.

“We weren’t organized nationally and beyond the local communities. There was the AHEPA organization, but AHEPA was a collection of local chapters, just as the church was a collection of local parishes,” Mike Jr. explained.

The Invasion of Cyprus and the Awakening of the Greek-American Lobby

In the tumultuous summer of 1974, the Greek American community found itself gripped by a fervor unseen in its history. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus had shattered the peace of the Mediterranean island, and across the Atlantic. In the corridors of Washington, D.C., a grassroots movement was ignited.

Andy Manatos, who had started working on the Capitol Hill in 1969, bore witness to those pivotal days when the fate of Cyprus became a rallying cry for Greek Americans across the nation.

Reflecting on the era, Andy sheds light on the community’s position in American society at the time. “A thing that surprises most people, but it gets back to what position Greeks were in in 1974. In my church, some of the more highly thought-of people were maître because they weren’t waiters. So, that was considered a position of some importance,” he explained.

Despite a significant presence in major cities across the nation, the Greek American voice often went unheard in the political arena. Andy remembers that during the first vote for the arms embargo against Turkey, he approached the then-senator of Pennsylvania, Senator Schweiker, and said, “if you vote with Senator Eagleton, your Greeks in Pennsylvania will be pleased.”

The senator dismissed him, claiming he didn’t have any Greeks in Pennsylvania. “Can you imagine, of all states, you know, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia?” Andy wondered. “We had so many Greeks, but we just didn’t have the profile that we have now.”

The invasion of Cyprus, however, served as a catalyst for unprecedented unity within the community. Greeks, notorious for their infighting since ancient times, once again united in the face of foreign threat.

In many regards, their response echoed ancient Greek Demaratus’s warning to King Xerxes before the Persian Wars. When the king sought his insight on whether the Greeks would dare to resist his attack, Demaratus advised, “beware, king, for though the Greeks may be divided among their cities, when the conqueror comes, they will unite as one tightly bound fist.”

And indeed, they did. Andy Manatos recalled gathering leaders from various Greek American groups in Senator Eagleton’s office. However, instead of strategizing, a dispute erupted, with some individuals accused of sympathizing with the junta, the military regime that ruled then Greece, and others labeled as communist loyalists.

“I emphasized that we didn’t have much of a choice. If we wanted to stand a chance at imposing an arms embargo on Turkey, we’d have to find a way to work together,” Andy recounted. “And really, believe it or not, the fighting among Greek Americans calmed down at that time in 1974.”

For the first time in their history, Greek Americans set aside competition and stood united under the banner of one goal: to impose an arms embargo on Turkey. Very soon, grassroots campaigns sprang up, demonstrating the power of activism and congressional advocacy in shaping U.S. foreign policy.

“Our people went crazy,” Andy recalled with excitement, reminiscing about the adrenaline of that time. “I mean, the lobby was tremendous. Everybody just really rose. It was a grassroots thing; it was just unimaginable.”

One notable example was two brothers who owed an insurance company. They literally shut down their business and, for like a month or two, did nothing else but persuade others to send telegrams to members of Congress.

It was truly a David versus Goliath battle, and the Greek community had to employ all their resourcefulness to achieve their goal. They employed innovative tactics, such as utilizing watch lines to establish connections with Orthodox priests and parishes across the nation. “We pulled off things in those days in government today would be a scandal,” Andy remarked with a smirk.

As he recounted, long-distance calls were prohibitively expensive back then. Hence, they made use of the Senator’s office on weekends, where watch lines were free, to reach out to church parishes nationwide. Andy vividly recalls an ingenious scheme concocted by a Louisiana priest.

“It was a church in the middle of nowhere. I suggested drafting a telegram,” Andy explained. “He said, ‘oh, yeah, we’re just making up Greek names.’ They were already flooding the Senate with telegrams from Greek-sounding people who were just made up,” Andy continued. “So, like I said, that one senator who didn’t even know he had Greeks. Well, he certainly knew after this overwhelming response.”

On the political front, Congressmen Paul Sarbanes, father of Rep. John Sarbanes, and John Brademas spearheaded the legislation for the arms embargo in the House, while in the Senate, Sen. Tom Eagleton, a non-Greek lawmaker from Missouri, took charge.

The involvement of Senator Eagleton, previously an obscure figure to the Greek community, might seem surprising. However, the unsung hero behind this legislative effort was Brian Atwood. Serving as Eagleton’s legislative advisor for foreign policy from 1972 to 1977, Atwood was the mastermind behind the idea for the embargo legislation.

By his side was always Andy Manatos, who served as the legislative director for Senator Eagleton. Though Andy’s expertise lay in passing bills rather than counseling on foreign policy, his Greek heritage once again placed him in the center of action. Just as his father had helped prevent an invasion of Cyprus, Andy now found himself fighting to remove the Turkish forces from the occupied island.

In the end, against all odds, they succeeded. A handful of U.S. lawmakers joined forces with a previously unknown community to defy the will of the White House and successfully impose an arms embargo on Turkey.

“Frankly, the invasion put us on the map. The Greeks’ reaction to the issue was tremendous,” Andy recalls with pride. “As you probably know, there’s only been one major foreign policy issue where Congress overruled the White House and State Department and that’s the Turkish arms embargo.”

The growing influence of the community became more evident in the subsequent years as the battle to maintain the embargo ensued. Senator Eagleton kept proposing various amendments to keep it in effect. It was then that he saw the wisdom in recruiting another colleague from a state with a sizable Greek population to introduce the amendment.

Senator Adlai Stevenson from Illinois did not know a lot about the Cyprus issue, yet he willingly introduced the amendment. The following week, upon landing at O’Hare Airport in Chicago, he found himself in an unexpected situation.

“In those days, you could walk right into the airport wherever you wanted to go. He got off the plane, and there were about two or three hundred Greek people,” Andy recalled. “They grabbed Stevens, who was a rather stiff, waspy Anglo-Saxon gentleman, and they carried him onto their shoulders, cheering wildly. And he loved it. He thought it was incredible.”

Confronting “Killer Kissinger”

Washington is a capital where American ideals often clash with special interests and the cynicism of unelected bureaucrats. The invasion of Cyprus was inevitably part of this wider story of American foreign policy.

During the Cold War, the foreign policy establishment viewed Turkey as an “indispensable ally,” serving as a bulwark in a strategic location against the Soviet Union. This resulted to a policy of appeasement that often meant turning a blind eye to even the most egregious violations of international law by Turkey.

After the invasion of the Republic of Cyprus, Turkey’s arrogance in Washington reached new heights. Mike Manatos Jr. recalls a story his father told him about the aftermath of the invasion, involving a briefing that the Turkish ambassador gave to a group of staffers on Capitol Hill.

“He had a big map, and he showed Cyprus being ripped off the coast of Turkey. And he said, ‘so you see, Cyprus should really be a Turkish island; it’s right there,’” Mike Jr. recounted. “That was the kind of arrogance Turkey had at the time because they didn’t face much pushback from the Administration.”

But Henry Kissinger didn’t just turn a blind eye to Turkey’s transgressions; he enabled its behavior by trying to circumvent any effort by Congress to hold it accountable.

Mike Jr.’s father, Andy, recalls a tense meeting with Elwood Maw, Kissinger’s lawyer and Under Secretary of State for International Security Affairs. Manatos emphasized the recent resolutions from the House and Senate, which reminded President Nixon that U.S. law mandates the immediate termination of arms supplies to any country using American weapons aggressively.

“[Elwood Maw] was fighting back, and I said, ‘but the conduct of the government has to be consistent with the law of the land,’” Andy remembered. “And he said, ‘well, then you’re going to have to change the law, because we’re not going to change our decision.”

Soon, Cypriots began calling Kissinger “killer Kissinger.” Andy recalls an intense encounter between Kissinger and William Calomiris, the president of the Board of Trade and one of Washington’s most prominent real estate developers.

“This Greek fellow was at the Kennedy Center. Kissinger comes walking in to sit down, and Bill said, ‘killer Kissinger,’ right in front of his face,” Andy narrated. “Everyone, of course, was horrified because, you know, Kissinger was considered such a god. But now he was a bad actor with everything he did on that issue.”

William Calomiris died many years before Henry Kissinger, and the anecdote between them remains in the memory of a few. Almost 20 years after Calomiris’s death, a Greek flag continues to wave atop the building that bears his name in Washington DC’s downtown.

A few years ago, Greek Minister of Development Adonis Georgiadis, accompanying Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis on a White House visit, spotted that flag and shared a picture on X, wondering about its presence.

From Rough Nixon to Gentleman Carter

In the years following, Andy Manatos mirrored his father’s path, transitioning from Congress to the White House. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter nominated Manatos to serve as Assistant Secretary of Commerce, making him the youngest sub-cabinet official in the administration.

However, the euphoria stemming from the passage of the arms embargo was short-lived as the Carter administration’s wavering support threatened to undermine their efforts. Andy remembers Carter’s trust in Turkey’s assurances with a sense of regret, a decision that ultimately led to the reversal of the arms embargo.

“Carter was a true gentleman, but also somewhat naive. He took the Turks at their word,” Andy reflected. “They argued it was a matter of dignity. They wanted to withdraw from Cyprus without the embarrassment of the embargo. Lift the embargo, they said, and we’ll continue withdrawing.”

During Andy’s tenure in the Carter administration, regular meetings convened in the Roosevelt Room, located adjacent to the president’s office. It was in one of these sessions that the administration announced its intention to attempt the lifting of the Turkish arms embargo, tasking each member with lobbying Congress.

Andy swiftly expressed his reservations to Frank Moore, a prominent figure in Carter’s administration. Feeling compelled by principle, he offered his resignation in protest. However, following consultations with President Carter, Frank conveyed the message that Andy could abstain from involvement and retain his position.

Reflecting on this episode, Andy’s son, Mike Manatos Jr., expressed profound pride. “It was a very noble thing for him to do. He worked his whole career to get this position. He was willing to give it up for the noble right reasons,” Mike Jr. said.

With sufficient support secured in both the House and Senate, the White House was on the verge of lifting the arms embargo. They turned to Senator Allen Cranston of California, explaining the Turkish desire for a graceful exit from Cyprus.

Cranston agreed to vote in favor, but not without conditions. He demanded assurances from the administration that Turkey would indeed continue its withdrawal from Cyprus, and if they ceased, the embargo would be reinstated. The administration consented, the amendment was adopted, and the arms embargo secured its place in history.

“Looking back, it’s astounding how government can sometimes be ridiculously dishonest. Even today from 1975, the White House sends a note to the Congress, telling them that Turkey is looking for a way to withdraw from Cyprus, even if not a single soldier budged. Isn’t that unbelievable?” Andy mused.

Into the Spotlight

Despite the lifting of the arms embargo, the Greek American community’s influence continued to grow. A few years earlier, one of the key organizers of President Kennedy’s inauguration included a Greek staffer.

His involvement secured Archbishop Iakovos of America’s role in delivering the prayer at the presidential inauguration, placing the Greek American community prominently in national politics. In subsequent years, Archbishop Iakovos delivered prayers at the inaugurations of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

“It kickstarted a tradition,” Andy reminisces. “For many years, the Orthodox Archbishop of America delivered the opening prayer, symbolizing our community’s presence and influence on the national stage.”

Yet, this tradition was abruptly halted by political maneuvering during President Carter’s inauguration in 1977. “They had appointed a fellow Albanian to be the head of his inaugural,” Andy explained. “And that guy said to somebody else, ‘one thing I’m going to do is knock that Greek priest out of that prayer.’ And he did, and we could never get it started again.”

For Andy, the loss of this tradition serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the need to safeguard other precious traditions the community has built. Chief among them is the celebration of the Greek Independence Day at the White House.

This idea emerged from humble beginnings. As Andy recalls, he was contacted by the father of a young schoolgirl from North Carolina who believed America should celebrate Greek Independence Day.

Andy coordinated with prominent leaders to mobilize the church and, thus, they passed the first resolution calling on America to recognize Greek Independence Day. From that point onward, they spearheaded efforts to transform this vision into reality, leveraging their connections and resourcefulness.

They didn’t have to look far away to find these connections. Andy’s cousin from Utah, Ambassador Tom Korologos, was a prominent lobbyist in DC who managed to open the Oval Office for the first celebration of Greek Independence.

The inaugural ceremony, orchestrated with modesty and simplicity during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, marked the inception of this new tradition for the community.

“It was just an Oval Office meeting; we’d have maybe eight people in there. It was very brief. I don’t think we sat down,” Andy remembered. “We stood and talked about Greek Independence, took a picture, and that is how it all began.”

Over the years, this small event evolved into a glamorous reception, celebrating the contribution of Hellenic ideals to American democracy and the historic-high ties between the two nations. The event is often attended by Greek politicians, prominent community leaders, businessmen, campaign donors, and celebrities like Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson.

Yet beneath the celebration lies a palpable sense of vulnerability. “This celebration is a very fragile thing. And if we ever missed one, we’d never be able to get it started again, because everybody wants it,” Andy explained. “The Archbishop’s story is a good example of why you’ve got to maintain the precedent.”

His determination to uphold that precedent was demonstrated during the early days of the Iraq War when the White House informed him that it was not possible to hold the ceremony, with American soldiers dying. But Andy, who remembered what happened to Archbishop Iakovos, was resolved to do whatever it took to maintain the tradition.

“I said to the White House, ‘look, all you need to do is tell me when the President can see the Archbishop for just five minutes. I don’t care in what city or in what building,’” Andy recalled. “So, when the President went to New York, I called Father Alex, and they went over. They got the picture, so we could keep saying to every president, ‘you can’t break the precedent, you can’t disappoint all the Greeks. They’ve done this now for 30 years.’”

Andy Manatos sheds light on the hidden advantages of the White House celebration, beyond the pomp and circumstance. The most significant benefit is the direct access it provides to the U.S. President. “It allows us to speak directly to the President about issues that, once filtered through his staff, might never reach his ears,” Manatos explains.

Another critical advantage is the influence it exerts on cabinet members who take cues from the President. “There was a time when we couldn’t even secure a meeting with an assistant secretary,” Andy recounts. “But if they hear the President just met with these Greeks, they think, ‘oh my god, these Greeks must be very important.’ Suddenly, meetings with assistant secretaries became easy, and we even gained access to cabinet members.”

In the face of skepticism and criticism that the event lacks substance and is merely a photo opportunity, Andy Manatos remains steadfast in his conviction. “There are subtle yet significant policy implications that go unnoticed,” he asserts. “Some Greeks have badmouthed the event, calling it ‘just a cocktail party.’ This is unfair because, from a policy perspective, it has been invaluable.”

Unofficial Ambassadors

They are perhaps the unsung heroes of Greek-American relations, but these everyday Greek-Americans have done enough to merit the title of unofficial ambassadors.

For most Greek-Americans it is common to bring their American friends to their parish’s Greek festival to try delicacies such as gyro and souvlaki.

However, some have gone a step further, introducing their influential friends to intricate political matters, such as the continuous plight of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople or the Cyprus refugees who still live with the hope that one day their homes would be liberated.

There are many such stories. Rep. Grace Meng (D-NY), for example, still remembers her Greek neighbor in Queens who taught her how to ride a bike.

Tasos Zambas from New Jersey took his friend Bob Menendez on a life-altering trip to Cyprus, which left such an impression that it transformed the future senator into one of the fiercest advocates for Cyprus reunification. Years later, Senator Menendez introduced landmark legislation, such as the East Med Act, that revamped the U.S. policy in the Eastern Mediterranean.

This is also the case with President Biden, who, as many people remember, was the last person to leave the room during the White House Greek Independence events, shaking hands and taking pictures with his numerous Greek friends.

Andy recalls that he was 28 years old when he first met Biden in Congress. The new Senator from Delaware was also very young, just 30 years old, and had his office down the hall.

Andy remembered his encounter with the Senator from Pennsylvania who, during the voting on the arms embargo, didn’t know he had any Greek constituents. So, he thought it would be a good idea to meet his new neighbor and inform him about the robust Greek community in Delaware.

“I introduced myself and said, ‘I know some Greeks in Delaware, and you probably aren’t aware of it, but there’s a significant Greek community in Wilmington.’ He said, ‘not aware of it? They were my greatest supporters. When I was running and nobody would support me, the Greeks were there.’”

L-R: Mike Manatos Jr. , Laura Evans Manatos, U.S. President Joe Biden, Tina Manatos (wife of Andy and mother of Mike Jr.), Andy Manatos.

In the years that followed, the friendship extended to the next generation, with Mike Jr. serving as a Senate page boy alongside Biden’s sons, Hunter and Beau. In that era, when there were no iPhones, page boys ran from office to office delivering bills that needed to be signed.

Biden’s friendship with the Greek community stood the test of time, even when he lost his presidential bid to Barack Obama. In the interim period between his loss and his nomination for Vice President, Andy happened to be exiting an event with Biden when they spotted the head of the Jewish lobby.

“Biden grabs my arm and says, ‘don’t move.’ He then says to the head of the Jewish lobby, ‘you know where I’ve been on your issues all the time, and I’m not going to change that because I believe in those issues. However, these guys, the Greeks, came through for me in spades, and you guys came through for me with nothing.’ He was very appreciative of our support. Like Greeks, Biden is a very loyal person.”

Although Andy has a lot of fond memories of Biden, he believes that it was another President, along with a brilliant diplomat, who made the most significant difference for Greece. In particular, he highlights the achievements of President Bill Clinton and Richard C. Holbrooke, the then Assistant Secretary for Europe.

Mike Manatos Jr. and the 42nd U.S. President, Bill Clinton.

According to Andy, they negotiated the Turkish withdrawal from the Imia islet, pressured North Macedonia to amend its Constitution to remove threats to Greek Macedonia, and successfully secured the release of five members of the Greek minority party Omonoia in Albania, who were facing potential execution. Their crowning achievement was pressuring France and Germany to lift their objections to Cyprus’s accession to the EU.

Andy attributes these successes to Bill Clinton’s long-standing friendship with David Leopoulos, a Greek pal he had since he was nine years old in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“We couldn’t get a president to do one damn thing for Greece or Cyprus for years because the foreign policy establishment was against us,” Andy said. “Clinton was also the first sitting president to visit the Ecumenical Patriarchate, sending a strong message to Ankara. Without David Leopoulos, it’s unlikely any of this would have happened.”

New Challenges to Greek-American Identity

In the bustling diversity of modern America, the Greek-American community has always stood out for its rich cultural heritage and strong family values.

However, the community now stands at a critical turning point, with the landscape of Greek-American identity evolving and presenting new challenges in an era where maintaining cultural identity is increasingly complex.

This holds true for the Manatos family as well. Mike Jr.’s insights reveal both the resilience of Greek-American traditions and the adaptive strategies necessary to preserve them in a rapidly changing world.

“Family is everything,” Manatos begins, attributing this core value to his Greek roots. Yet, his perspective is broadened by his own family dynamics; neither his mother nor his wife is Greek, yet they are deeply embedded in the community.

“My mother (Tina Manatos) is more Greek than most Greeks I know. Without exaggeration, when I was 10 years old, I came to my dad and said, ‘did you know Mom is not Greek?’” Mike Jr. remembers. “And no one wanted me to marry a Greek woman more than my mom.”

Mixed marriages are a reality that the Greek-American community must navigate. Manatos views them as both a challenge and an opportunity, illustrating how non-Greeks can embrace and enhance Greek culture. His own marriage to a non-Greek woman, Laura Evans, who shares and values the Greek ethos of family, faith, and community, underscores this point.

However, he acknowledges the concern that these marriages might dilute cultural identity and lessen advocacy for Greek national interests. “I think that’s a valid concern,” he concedes. Data indicate that the preservation of Greek identity is increasingly shrinking as each generation becomes more integrated into broader American society.

Mike Jr. highlights a significant decline in the number of individuals who professionally support the national missions of the Greek-American community. “One generation later, there are like seven people who hold leading positions,” he says, pointing to a stark reduction in active engagement.

But he also sees potential. The exposure of non-Greeks to Greek culture and values through marriage can foster a deeper appreciation and connection, potentially expanding the community’s cultural influence.

For many of their friends and prominent members of the community, the Manatos name is synonymous with unwavering support for Hellenic causes in the halls of Washington.

However, within a community often marked by internal strife and rivalries, there are those who raise doubts about their leadership on certain political fronts. Yet, even critics, who may oppose them politically, tend to speak with high regard about the tight-knit bond within the Manatos family.

Perhaps, ultimately, this sense of a family ideal is the thread that weaves Andy and Mike Jr.’s modern life with their ancestors’ roots in Wyoming and back to Crete. As Andy insists, it’s this “old village wisdom” that continues to guide them.

“Of course, we are different today,” he admits. “But my uneducated grandmother could tell you what to do and what not to do to have a great life better than a Harvard professor. That living wisdom is still a part of us.”