Ask anyone abroad about Greek food, and chances are they will be able to name at least one or two famous edibles like souvlaki or moussaka. Ask them to describe the Greek diet and most – including many Greeks – will struggle to give a clear answer. And yet, it is the prototype for the world-famous Mediterranean diet. This clearly demonstrates the need for Greece, now more than ever, to tap into one of its most overlooked national assets: the traditional diet that has stood the test of time and consistently ranks among the world’s healthiest.

Despite soaring interest in healthy eating, wellness and health education, not to mention the obvious public health and economic benefits, Greece still appears to be lagging behind in fully leveraging the power of one of its most tangible assets: the Mediterranean diet. The key reasons for this, explains nutritionist, author and Mediterranean lifestyle expert Elena Paravantes, MS, RD, are a lack of education, understanding and consistency.

Greece’s Connection to the Mediterranean Diet

“Greece is in essence the birthplace of the Mediterranean Diet. The origins of the diet can be traced back to the 1950s on Crete, where the typical diet was rich in olive oil and vegetables, but frugal when it came to animal products. People also fasted frequently, often abstaining from animal products for more than 200 days a year,” Paravantes explains.

The Mediterranean diet is described by physicians and nutrition researchers in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition as a diet based on food patterns typical of Crete, the rest of Greece, and southern Italy in the early 1960s, where adult life expectancy was among the highest in the world. “So that is the connection,” Paravantes tells TO BHMA International Edition. “The Mediterranean diet is essentially the traditional Greek diet.”

The Mediterranean diet was first recognized in the late 1940s when The Rockefeller Foundation studied nutrition on post-WWII Crete. Despite poverty and limited healthcare, the locals were remarkably healthy, with low rates of heart disease and cancer. They also lived longer than Americans, who ate a typical Western diet of meat and butter. Researchers linked this finding to a diet rich in olive oil, vegetables, legumes and fruits, with little meat.

“This study was groundbreaking, because it was one of the first to show how diet can directly affect health,” Paravantes explains. It also paved the way for the landmark “Seven Countries Study”, which further confirmed that Mediterranean populations, despite their relatively high-fat diets, had low rates of heart disease, largely due to the consumption of healthy fats from olive oil.

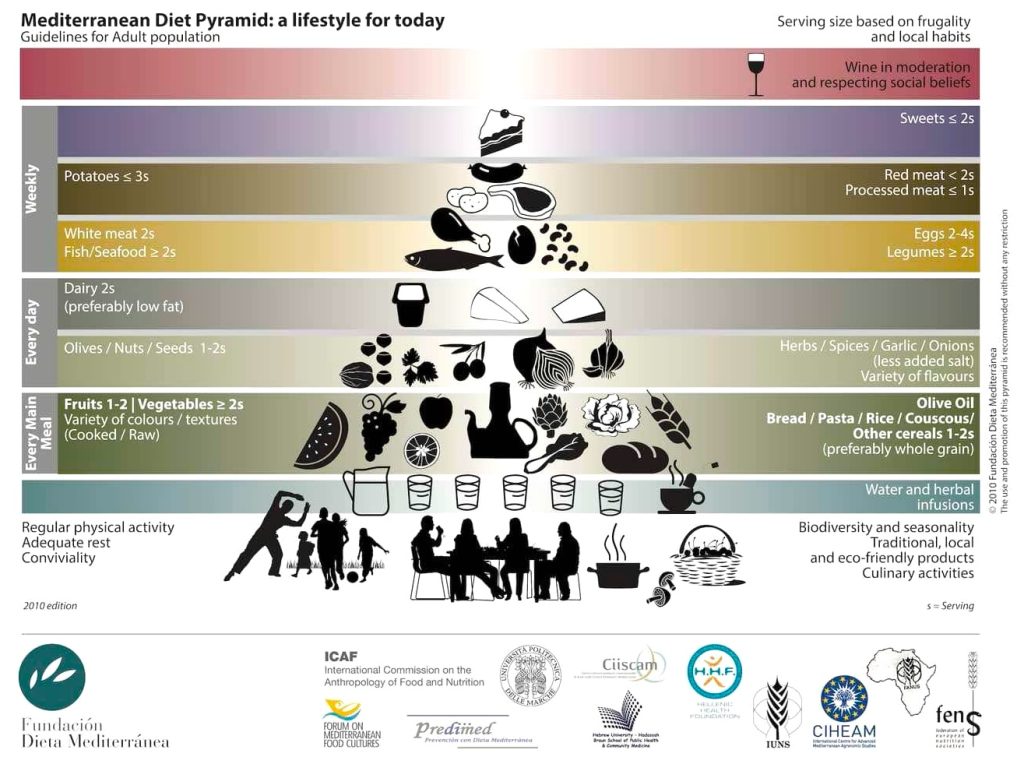

By the 1990s, the Mediterranean diet had been formally introduced to the world as a food pyramid. Based on traditional eating patterns from Crete, Greece, and southern Italy, it is now globally recognized as a model for healthy living, supporting longevity and preventing chronic disease.

Shift in Greek Eating Habits

Fast forward to 2022: the World Health Organization (WHO) European Obesity Report ranked Greece third among EU countries with the highest rates of overweight and obese children under the age of five. A Eurostat report from that same year revealed another worrying trend: Greece also had one of the highest percentages of overweight adults over the age of 16.

Paravantes attributes this shift to several factors–most significantly, a failure to effectively communicate the value of the Mediterranean diet not just to the public, but also to key stakeholders such as restaurateurs, chefs, farmers, politicians, healthcare providers, hospitals, and schools.

She also points to a long-held belief among Greeks that traditional cuisine – the basis of the Mediterranean diet – is outdated and inferior, and that traditional dishes are too simplistic.

A first step towards changing this mindset, she says, is understanding the crucial difference between Greek food today and the traditional Greek diet.

“Greek food already enjoys a high level of international recognition, thanks in large part to Greek-American immigrants who served Greek foods in their U.S. restaurants,” Paravantes explains.

“Many of those establishments featured Greek dishes, perhaps most famously, the gyro. While not authentically traditional, it’s widely associated with Greece, along with dishes like tzatziki and Greek-style potatoes.”

However, she points out, the authentic, home-cooked Greek food which is the foundation of the Mediterranean diet has not achieved the same level of global recognition. “In recent years, we’ve seen more thoughtful presentations and careful portrayals of Greek cuisine,” she admits “but it still hasn’t reached the visibility or prestige that other world cuisines enjoy.”

This stems in part from post-war attitudes in Greece, she explains. The generations who lived through hardship came to associate vegetables and olive oil, the very staples of the Mediterranean diet, with poverty and lack.

“These were ingredients they had in abundance,” she says. “By contrast, butter, sugar, and meat were rare and considered symbols of wealth and progress.”

As a result, modern Greeks began to reject the very foods that once made their diet one of the healthiest in the world. Instead, they embraced the Westernized diet – high in processed foods and animal fats – which “we now know neither reflect authentic Greek cuisine nor support good health”.

‘Practice What We Preach’

If Greece wants to promote the traditional Greek diet on a global scale, the first step, says Paravantes, is “to practice what we preach, which means promoting the Greek diet in Greece”.

A critical first step, she tells TO BHMA International Edition, would be to introduce Greek ingredients and traditional dishes in schools and hospitals.

Hospitals in Greece often serve Westernized meals, missing an opportunity to highlight the health benefits of the very diet Greece is known for.

“Menus could instead include traditional Greek foods,” she says. “There is such a wide variety, not only vegetables, but also meat dishes that are far healthier.”

This also applies to schools. Having overseen food programs in both U.S. hospitals and Greek schools, Paravantes knows firsthand how impactful early dietary habits can be. Introducing children to the flavors and health benefits of their own culinary heritage, she suggests, could be the first step toward reclaiming Greece’s identity as a global model of healthy living.

Raising Awareness in Greece First

In recent decades, a misconception has taken root across Greece that traditional Greek dishes are heavy, difficult to make, or that children dislike them. Paravantes says these are fallacies.

“None of these beliefs are true, and proper education can help people understand that they can start eating better.”

While several public awareness campaigns have aimed to revive interest in the Mediterranean diet, Paravantes argues they’ve often fallen short. “They highlight the benefits, but don’t offer practical solutions. People need tools: recipes, guidance, and support to actually cook these meals at home.”

Another key issue, she adds, is access to quality Greek products. “In the past decade, it has become harder and more expensive for Greeks to find their own country’s produce. That needs to change, if we want to promote the Greek diet in a meaningful way.”

Branding Greek Cuisine

So the question is, have Greek policymakers and stakeholders successfully branded the Greek diet in the way Italy, France, and Spain have tied their cuisines to national identity?

“I wouldn’t say Greece has effectively branded its cuisine; and if it has, it’s not a representation I’d call accurate, fair, or even honest,” she says. “Many foreigners still associate Greek food with meat, when in fact this is not historically the case. So, there’s work to be done in this respect,” Paravantes says.

Admittedly, a large part of the traditional Greek diet was left behind in the mid-1980s, when Greeks became wealthier, international food chains and products entered the market, and lifestyle trends pushed Greeks toward more Westernized eating habits.

There is hope however. A welcome shift is underway. Younger generations are rediscovering Greek ingredients and traditional practices, driven by growing interest in healthy living and nutritional awareness.

To truly re-establish the Greek diet, both locally and internationally, as a scientifically backed, health-promoting lifestyle, Paravantes says Greece needs a unified and consistent national branding strategy.

“Right now, we see scattered efforts, but they’re disconnected,” she explains. “What’s missing is a cohesive strategy: coordinated marketing, a strong visual identity, messaging that highlights health benefits, cultural heritage, and culinary uniqueness; everything that would resonate with both consumers and tourists.”

Equally important is supporting the export of Greek products. “As a Greek diet expert, I often get questions like, ‘What’s the best brand?’ or ‘Where can I find this product?’ And often, producers here don’t even know where their items are being sold abroad,” she notes. A central hub or platform, she says, could streamline this process and ensure greater visibility and access to authentic Greek products worldwide.

Mediterranean Diet: A Powerful Tourism Product

Promoting the Mediterranean diet as a cornerstone of its tourism offering is one of Greece’s greatest unutilized opportunities. Nonetheless, some steps have been taken in this direction: : most notably through initiatives like Greek Breakfast, introduced by Giorgos Pittas, and more recently through efforts by the Greek National Tourism Organization (GNTO), which has started to promote the Greek diet as part of a broader health and wellness package.

Tourism Minister Olga Kefalogianni has repeatedly emphasized the ministry’s commitment to showcasing Greek products and the traditional diet. Again, though however, these actions lack coordination and consistency.

“I see the Mediterranean diet as a vehicle for promoting health and wellness tourism,” she says. “We talk a lot about culinary tourism, but health and wellness tourism is still largely untapped. With interest in longevity and wellbeing on the rise globally, Greece is ideally positioned. The Mediterranean diet is more than food; it’s a lifestyle. And Greece has the history, the environment, and the knowledge to lead the way.”

With regards to culinary tourism, Paravantes believes Greece is a natural destination, but needs to package and present its offerings more effectively. “Tourism packages should include cooking classes, food and wine tours, olive oil experiences, and the promotion of local food festivals. These would have far more impact than sporadic efforts.”

She also emphasizes education as a long-term strategy. “To truly promote the Mediterranean diet globally, Greece should establish itself as a center for studying it. Universities and institutions here could attract people from all over the world interested in studying the diet.”

To her dismay, many Greek culinary schools don’t even teach Greek cooking techniques, she adds. “In contrast to countries like Italy or France, where people travel to specifically to study their cuisines. Greece has that same potential, but we need to start treating our food culture and heritage with the respect.”