Though Greek society tends to avoid talking about the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), which is one of the darkest chapters in Greece’s history, filmmakers keep on returning to its murky depths to tell their stories.

The latest such film to grace Greek cinemas is Yiannis in the Cities, directed by Eleni Alexandrakis. Set against the backdrop of the aftermath of the conflict, the film is an adaptation of two autobiographical novels by the Greek author Yiannis Atzakas: Diplomena Ftera and Tholos Vythos [Murky Deep].

Giannis in the Cities relates the trials and tribulations of its eight-year-old protagonist, the son of a Communist partisan, as he is torn from the warmth of the family home on the island of Thasos in the northeastern Aegean. Wanting to ensure the best possible education for Yiannis, who is in her care, his grandmother Venetia hands him over to Eranos, a philanthropic project headed by Queen Frederica of Greece.

Eranos includes the Paidopoleis, or ‘child cities.’ In response to the widespread suffering caused by the war, they provide a home for thousands of children affected by violence, displacement, orphanhood, and poverty. However, they also had a political mission and seek to mold the children’s ideologies through a nationalist education and anti-communist propaganda.

As Atzakas writes in “Murky Deep”, which won the National Award for a Novel in 2009: “When I entered in ’49, I was eight years old, and when I left in ’55, I was almost fourteen—six years in total. These are precisely the lost and locked-away years you are searching for, and only I can tell you about them—they are my six years.”

Still frame from Alexandrakis’ film Giannis in the Cities.

Alexandrakis, who spent 16 years working on the project, explains that the film “focuses on the life of Yiannis, his thoughts, his soul, and his journey from the day he’s uprooted from his natural environment and has a new world imposed on him, to the moment he finally confesses all he has experienced to the man who has haunted him by his absence for so long.”

Writing in TO BHMA, film critic Yiannis Zouboulakis reiterates this focus on the child’s perspective: “It is the child’s gaze that interests Alexandrakis.” He goes on to note that, “By focusing on one of these children, she crafts a masterful narrative of a tragic experience—one that will cast a heavy shadow over the child’s psyche for the rest of his life. Shot in black and white, minimalist, and free of melodramatic embellishments, ‘Yiannis in the Cities’ stands as Alexandrakis’ finest and most profound fiction film.”

The movie premiered at the 65th Thessaloniki Film Festival in November 2024 with English subtitles. It is now embarking on its international journey, the first stop on which will be the Sofia Film Festival later this month.

A Divided Era – A Benefactor

“The Greek civil war takes place within the context of a broader conflict—the Cold War—where, once again, two worlds are in conflict. All of humanity is divided in two, and Greek society along with it,” historian Tasoula Vervenioti explained during the presentation that followed the Thessaloniki screening.

On one side was the UK-backed conservative Greek government, supported by the Hellenic Army. On the other, the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE), which originated from EAM (the leftist National Liberation Front, a major resistance organization). The Greek Civil War is considered the first of the Cold War’s proxy conflicts.

While Greece’s liberation from the Nazi Occupation left approximately 400,000 orphans behind, the Greek Civil War exacerbated the issue of protecting children who had suffered from violence, bombings, and hunger.

Vervenioti explains: “In a country which had emerged from the devastation of WWII only to be plunged into an even more catastrophic conflict, philanthropy was not only socially acceptable, it was essential.” She distinguishes philanthropy from social welfare, noting that philanthropy depends on the generosity of benefactors, while social welfare is a civil right.

Disliked by leftists for her membership of the Hitler Youth and by conservatives for her German heritage and strong-willed nature, which clashed with traditional female stereotypes, Queen Frederica of Hanover established Eranos (Charity Drive), whose official title was “Charity for the Welfare of the Northern Provinces of Greece Under the High Protection of Her Majesty, the Queen,” by Royal Decree on July 10, 1947.

That same month, its first “Saint Irene” facility was inaugurated in Thessaloniki. Another 52 Paidopoleis across the country would follow, all of which sought to provide Greek children—most of them from leftist families, whose parents were either imprisoned, dead or in exile–with “the necessary protection, so they will not fall prey to diseases or anti-national ideologies.”

This was not just the Queen’s response to the tragedies of war, it was also a bid to establish her image, her autonomy, and her political influence within Greek society. After the launch of her mission, Frederica would use radio speeches and newspapers publications to spread her message, and it worked: her image would later be used in pamphlets as a national symbol, the “mother of the people and the army,” and the “first mother of Greece”.

File photo: Queen of Greece Frederica during a visit at the Royal Technical school on the Dodecanese island of Leros.

Recalling his experiences in one of the Child Cities, in Kifissia Athens, Atzakas writes: “Back then, the only thing I knew was that my father was gone—he had left a long time ago and never returned. What our fathers did, where they were, what had happened to them, we didn’t know at the time… But for the Queen to take us and bring us here, so far away from our homes, something very bad must have happened—something we weren’t supposed to know.”

Despite it being the Queen’s personal project, Eranos, as Vervenioti explains was funded by voluntary contributions, but primarily from public stable sources such as taxes on cigarettes, bottled wines, entertainment venues, luxury goods, and theater and cinema tickets.

Initially planned to last just six months, the Queen’s fundraiser, Eranos, proved to be remarkably enduring. In 1956, it was renamed Royal Welfare, and during the Greek Junta, it was rebranded as the National Welfare Organization (EOP). In 1998, it was integrated into the National Organization for Social Care and later, in 2003, into the National Social Care System.

The Debate

In 1948, as the war continued, the DSE began transferring war-affected children across borders into Eastern Bloc countries. Pro-communist voices termed this practice “child-saving”, but government officials dubbed it “child-gathering”, employing the word used for the forced recruitment of Christian boys into special Ottoman battalions under Turkish rule.

This DSE’s actions attracted international attention, and Cold War narratives fueled the urgency with which Greek children were placed in the Queen’s Child Cities and exposed to their anti-communist agenda.

To this day, historians continue to debate whether the Child Cities were a genuine humanitarian initiative or a vehicle for indoctrination. The people who grew up in these institutions have expressed a range of opinions—some nostalgic, others critical.

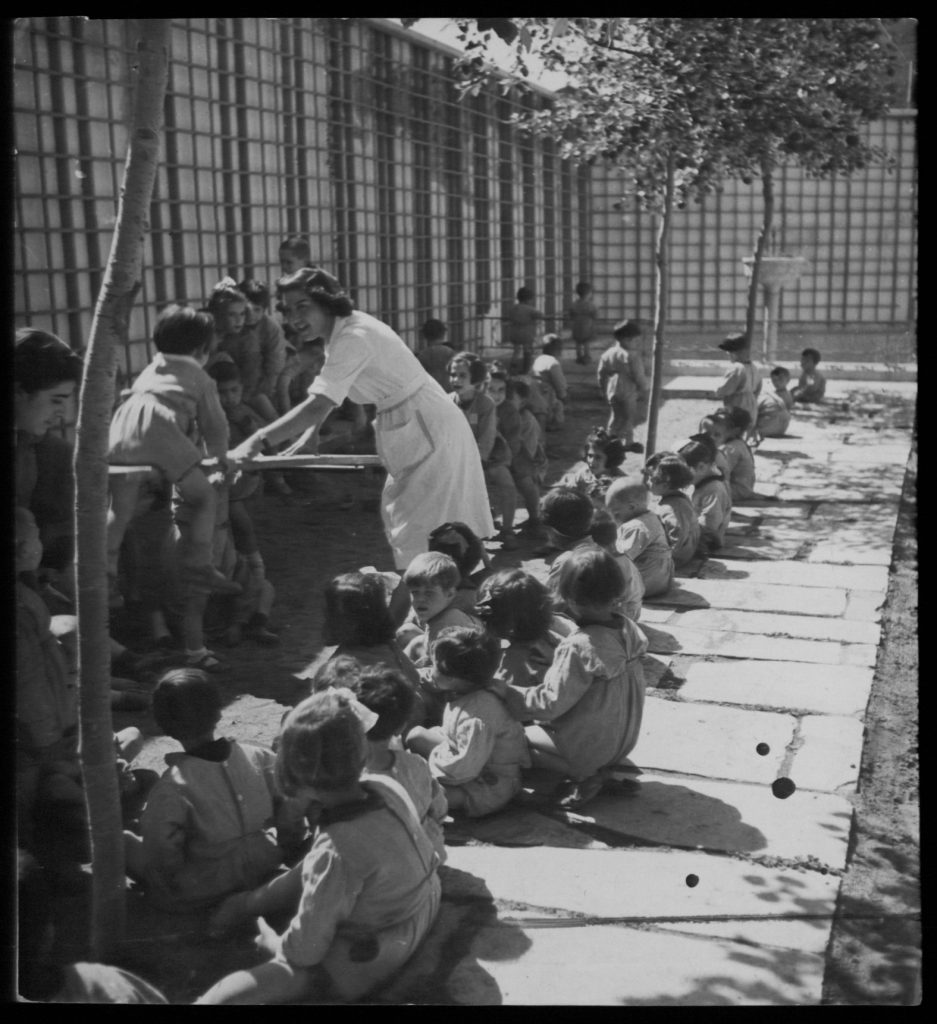

A file photo taken at the child city “Kali Panagia” in 1957, Veria, in central Macedonia, Greece. Photo by dimitris Charisiadis, Benaki Museum Archives.

Atzakas, in an interview with TO BHMA, says that his harsh upbringing in his grandparents’ village allowed him to endure the almost military life in the Paidopoleis. However, he adds, “I was fortunate to meet two remarkable individuals there who undoubtedly shaped my journey toward literature and education, steering me away from the humble craft of carpentry, which had been my childhood dream in the village.”

Naming his teachers in the fifth and sixth grades, he adds, “They were the ones who, with their praise, gave me my first wings.” He also acknowledges the powerful role of his camp leader, whom he saw as an older sister. Alexandrakis’ film includes scenes of her “comforting their feeling of emptiness” and reading them stories. “That must have been the first time I experienced the captivating power of great literature,” he recalls.

In his interview, Atzakas reflects on overcoming his trauma and credits literature as a redemptive process.

“Looking Back to Move Forward”

The Greek Civil War remains a deeply divisive subject which is skipped over in school history books but rarely properly addressed. Yet its reverberations continue to shape public discourse, politics, and personal ideologies in Greece.

Vervenioti concludes: “The civil war has not been negotiated in society. And I believe that if Greek society—if all of us, as a social body–cannot negotiate the civil war socially, we will remain unable to properly shape our future. Because the life we make for ourselves, how we dream of our individual lives and our social life, relates to the past. Based on the past, we can truly build our future.”

However, Vervenioti asks the crucial question: “When is a war truly over?”