On Monday March 10, Nikos Papadopoulos, a member of the Greek Parliament, waltzed into the National Gallery in downtown Athens and began ripping art works off the walls. Shouting that the works were blasphemous, Papadopoulos managed to hurl three pieces to the ground, shattering the glass in the frames, before pushing past the attendants and tossing one more before he was apprehended.

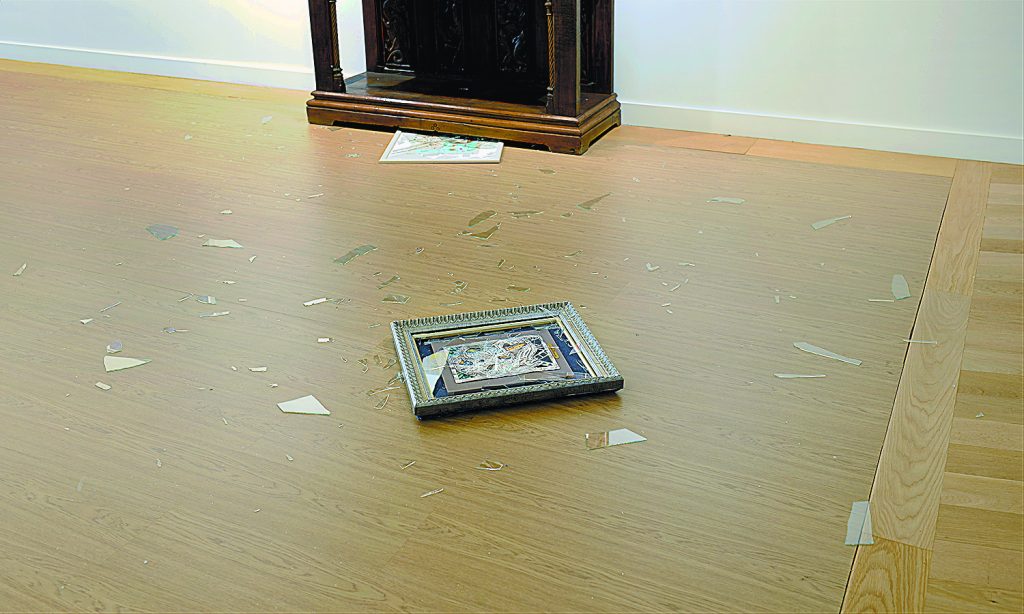

Broken artwork at the Athens National Gallery after it was vandalized by ultra-conservative party Niki (Victory) MP Nikolaos Papadopoulos, March 10, 2025. AMNA/ Athens National Gallery

Papadopoulos spent the next several hours held in the basement of Greece’s National Gallery as the police awaited word from the prosecutor on whether his acts constituted a felony or a misdemeanor. Since he was a MP, the distinction mattered.

Had his actions been judged a felony, Papadopoulos would have been taken to Athens’ central police station, because the crime would have been one of the rare instances of an MP being caught in flagrante delicto-in layperson’s terms, red handed. However, if his actions constituted nothing more than a simple misdemeanor, the MP’s parliamentary immunity would come into effect. Because no member of the Greek Parliament can be automatically charged, arrested, or detained for a crime while in office.

Parliamentary Immunity exists as a legal concept in most parliamentary systems; the idea is to allow parliamentarians to govern without having to fend off an endless stream of legal suits relating to their work. Members of the European Parliament also enjoy immunity with regard to their opinions or votes, and cannot be arrested or detained during Parliament sessions.

In Greece, Parliamentary Immunity is fairly wide-ranging. Greek MPs cannot be charged for any crime, whether it was committed during their time in office in the course of their duties, or before it. In fact, they can only be charged if they are caught in the act of committing a serious crime, or if parliament votes to suspend a particular MP’s immunity.

A handful of trials against various members of parliament who have had their immunity suspended are currently underway. Greek Solution President Kyriakos Velopoulos is facing a defamation suit from a retired navy officer, and Course for Freedom president Zoe Konstantopoulou has been taken to court for defamation by a police officer convicted of killing a teenager in a high-profile case. Eleven deputies elected with the Spartiates party are also facing misdemeanor charges for deceiving voters and being secretly affiliated with a convicted neo-Nazi.

Members of the Greek government enjoy a different form of immunity, with an even higher barrier to prosecution. As stated in the Greek constitution, “Only the Parliament has the power to prosecute serving or former members of the Cabinet or Undersecretaries for criminal offences they committed during the discharge of their duties, as specified by law.”

To put it simply, a member of the government can only face criminal proceedings for crimes committed in the context of their position, if the Parliament decides to pursue the criminal proceedings.

A special parliamentary committee must first be set up to conduct a preliminary examination into the alleged crime. If parliament decides to proceed with the case, the trial takes place in a special court made up of judges from senior courts.

This ministerial immunity has proved a sore point with the Greek public in recent months, in the light of widespread outrage over the Tempi train crash. That no attempt has been made to investigate the responsibility of members of the government with regard to the crash – be it the minister of transport, or the minister of citizen protection – has caused an outcry.

One protester at the Tempi demonstration of February 28 told To BHMA International Edition, “I don’t understand why there should be parliamentary immunity. When someone is responsible for crimes, for thefts of money, for murders why should there be parliamentary immunity.” Another stated with frustration, “We can’t allow officials to simply cover for each other.”

This peculiarity of the Greek system was actually been criticized by the European Prosecutor’s office, when the Hellenic Parliament refused to prosecute 23 members of the Greek government it had indicted for responsibility in the Tempi train crash. “According to the Greek Constitution, only a parliamentary committee can investigate such cases,” EU Prosecutor Laura Kövesi told EU lawmakers, her frustration evident. “This provision contravenes the regulation of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office. So, we could not proceed because the part of the case that corresponded to us would have to be sent to this parliamentary committee. As I told you, this is inconsistent with the European regulation and should be changed.”

Greece may be outside the norm in this respect, but it is not alone in Europe – a European Commission study from 2013 notes that a similar situation holds in France, Germany, Italy, Albania, and Turkey, where MPs can only be prosecuted with the authorization of the grand Assembly. However, the protections provided for members of government are not nearly so strict in the remaining countries of Europe.

“Parliament is a political institution, and thus totally unrelated to criminal procedure and the application of criminal law,” said Spyridon Vlachopoulos, professor of Public Law at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. “These are things that should be decided by judges, not politicians, who think with political criteria and who, in many cases, do not have the necessary knowledge and competence to decide on a minister’s criminal responsibility.”

Vlachopoulos noted that parliament’s competence in such matters can also turn Cabinet members into a privileged category of citizen: “It is also a matter of equality before the law. Many argue that this system violates the principle of equality, since we have a special category of citizens—ministers—who enjoy different privileges in relation to criminal procedures than ordinary people,” he stated.

After the record-breaking protests over Tempi, in which hundreds of thousands of Greeks went on strike across the country demanding accountability, with thousands shouting “Quit now” outside the country’s parliament, one such deliberation into the possible prosecution of a government minister was set in motion.

On March 4, the Greek Parliament voted to investigate Minister Christos Triantopoulos, Deputy Minister to the Prime Minister in 2023 at the time of the crash, over his handling of its aftermath. The inquiry will seek determine whether a breach of duty occurred, and decide if a trial should take place. Though he denies any wrongdoing, Triantopoulos resigned in February 2025.

Though the stakes are much higher than smashed art, and while Greece’s National Organization for the Investigation of Air and Rail Accidents and Transport Safety found a series of government-level failures leading up to the Tempi collision, Parliament is not currently looking into the prosecution of any other members of the government in relation to the Tempi train crash.