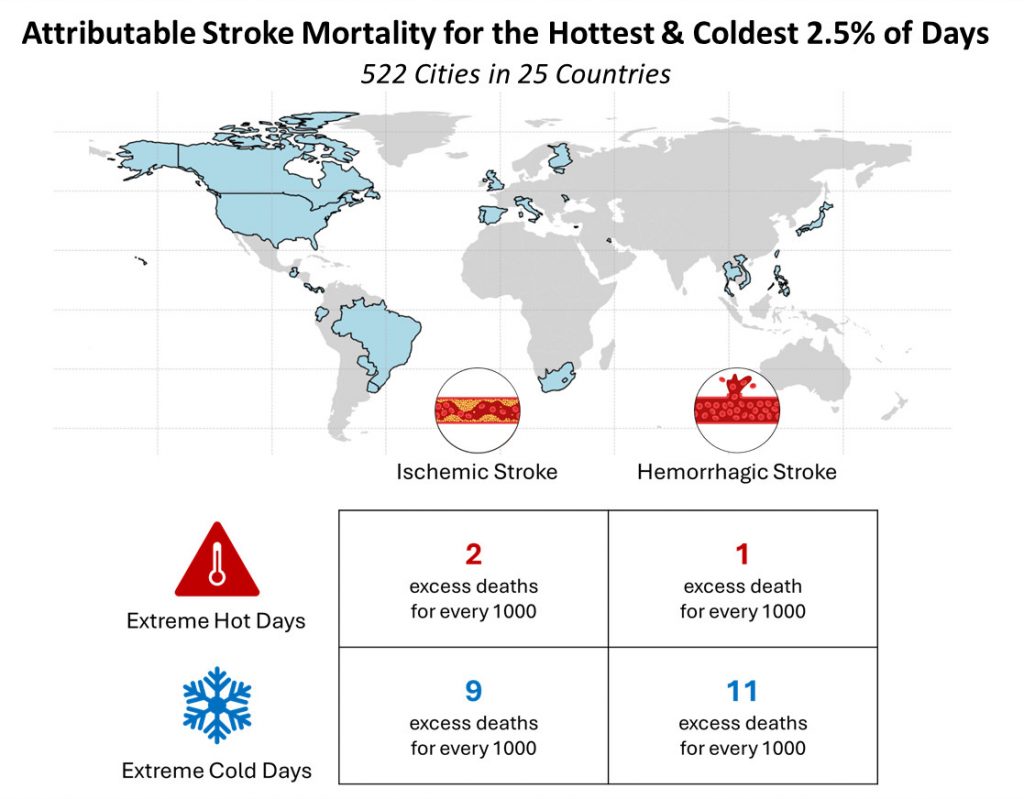

In the largest study investigating the relationship between extreme temperatures and stroke mortality to date worldwide, a team of researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that out of every 1,000 deaths from ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, approximately eleven are attributed to extreme cold or extreme heat.

The study, led by Barak Alahmad and published in the journal Stroke, analyzed data from the global environmental health consortium “Multi-Country Multi-City Network”, between 1979 to 2019 and found 3.4 million deaths from ischemic strokes and more than 2.4 million deaths from hemorrhagic strokes in 522 cities across 25 countries worldwide.

Dr. Alahmad explained to AMNA that “strokes are the second most frequent cause of death worldwide, and the burden caused by extreme temperatures is very significant in terms of global health. The idea behind this research was to address healthcare professionals and make them understand that climate change is not just a battle for environmentalists; it is also a battle for them and their patients.”

He noted that each country has a different definition of what constitutes extreme temperature, but clarified that “In each city, we defined days with extreme temperatures as the 2.5% of the hottest and coldest days.”

He explained that the team found that for every 1,000 deaths from ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, 2.5% of the days with extreme temperatures during the studied period contributed to 9.1 additional deaths due to cold and 2.2 deaths due to heat.

Greek Harvard Professor of Environmental Sciences Petros Koutrakis was also part of the research team and mentioned to AMNA that “beyond the cardiovascular impacts of high temperatures, recent studies have shown an increase in suicides and emergency hospital visits for mental illnesses.”

In a recent speech at the Greek Parliament, Koutrakis highlighted that Greece will be significantly affected by climate change and its impacts will lead to an increase in wildfires, more heatwaves and floods, less snow in the mountains, water shortages, agricultural destruction, increased electricity consumption, reduced productivity, less tourism revenue, and higher mortality rates.

He also pointed out that the climate crisis will mainly affect people with pre-existing health problems. “Given the moderate health status of the Greek population, the impacts of climate change will be dramatic. We need to change many bad habits if we want to prevent another crisis in the healthcare system, by reducing smoking and alcohol consumption, eating less meat, avoiding using pesticides, and protecting our environment,” he observed.

The study also found that low-income countries had higher mortality rates from heat-related hemorrhagic strokes compared to high-income countries, a conclusion that was not definitive, however, for cold-related hemorrhagic strokes. The researchers hypothesize that good infrastructure and indoor temperature control systems, lower rates of outdoor work in high-income countries, and poorer quality healthcare in low-income countries could explain the differences.

The authors noted that limitations of the study were that rural areas and countries in South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East were underrepresented. Greece was also not included in the study, as data from Southern European countries were only available for Cyprus, Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

Additionally, they clarified that the study focused only on deaths from strokes. Further research on non-fatal strokes would provide a better understanding of the actual negative effects of extreme temperatures.