Germany’s unilateral decision to close its borders as of today, Monday September 16, sent shockwaves through European countries, including Greece, where authorities fear an influx of irregular border crossings or returns in the wake of Germany’s border policy.

Greek media reports have noted a flurry of activity within the Greek administration both on domestic and international levels, while policy analysts ponder the impact of Germany’s border policy on Dublin III, the new Migration Pact and the Schengen Zone.

Greece’s primary concerns are a possible rise in irregular migrant arrivals at its borders, an increase in migrant returns from Germany and other EU countries, and growing political tension within the New Democracy party, as Germany’s hardline approach could embolden Greece’s right-leaning factions.

However, Angeliki Dimitriadi, Senior Research Fellow at ELIAMEP and a leading expert on migration, tells To Vima English that many of these fears are unfounded.

Germany’s Border Policy: The ‘Return’ of Dublin III?

European leaders, policy analysts and media have been sent into a tizzy over the news, trying to grasp what exactly the decision means for a key element of Europe’s architecture – the Schengen zone – as well as its interaction with Dublin III and the newly voted but yet-to-be-implemented Migration Pact.

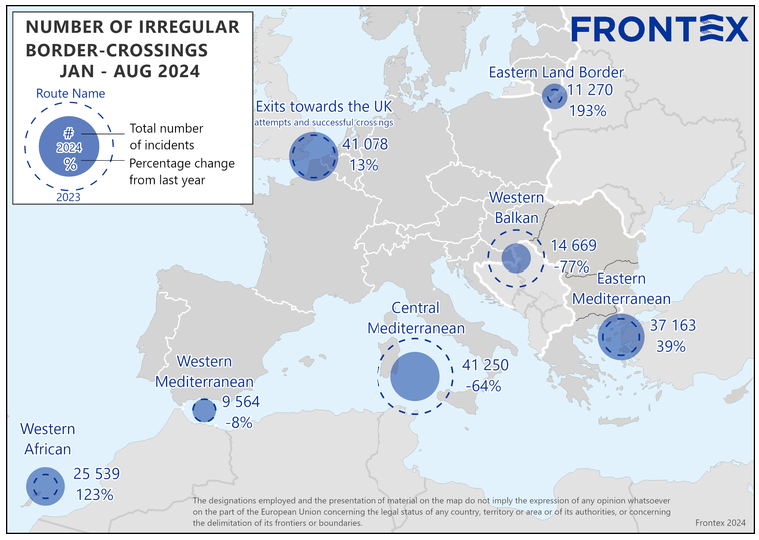

It has also raised the alarm for countries like Greece, which are the first point of entry into Europe for irregular migrants, asylum seekers and refugees. The fears are that the decision will put further strain on Greece’s reception and asylum system, either through arrivals or more returns.

The concerns about returns has to do with Dublin III, which puts the burden of processing asylum applications on the first EU country an asylum seeker enters, regardless of where the migrant travels to afterwards. And, asylum seekers can be sent back to the country of entry, which Greece says would effectively make it a holding country for Europe’s migrants.

Dimitriadi, however, dispels these concerns, noting that the focus on Dublin III is misplaced. “The Dublin III framework never went away—it’s still in place—and Germany’s border controls do not change that,” she explains.

Even though the regulation remains active, Dimitriadi points out that Germany has struggled to enforce “Dublin returns” due to rulings from its own courts. “German courts have found that conditions for refugees in countries like Greece do not meet European standards for reception and living conditions, which limits their ability to return migrants to Greece,” she adds.

Pope Francis visits the Refugee Camp of Kara Tepe in Mytilene, Lesbos, during his three days visit in Greece on Dec. 5, 2021 / Επίσκεψη του Πάπα Φραγκίσκου στο Κέντρο Υποδοχής Προσφύγων του Καρά Τεπέ, Μυτιλήνη, Λέσβος, κατά την τριήμερη επίσκεψη του στην Ελλάδα. 5 Δεκεμβρίου, 2021

The Migration Pact and Schengen: What’s Really Changing?

The EU’s recently passed Migration Pact, set for full implementation by January 2025, includes provisions for the establishment of border controls during times of crisis. However, what qualifies as a “crisis” is still unclear. Despite the Migration Pact being hailed as a milestone for EU cooperation on migration, its implementation is still in the planning stages, and member states are yet to submit and approve their strategies.

Thus, technically, Germany’s border policy is not in violation of the Pact, as it has not yet been fully implemented. “Germany is acting under provisions that allow Schengen countries to impose temporary border controls for up to six months,” Dimitriadi clarifies.

Interestingly, Germany already had selective border controls in place with several neighboring countries—Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Poland, and France—prior to this new announcement. Dimitriadi emphasizes that Germany is not alone in this approach: “In 2024, around 10 European countries reintroduced some form of border controls, citing reasons ranging from counter-terrorism to controlling irregular migration.”

The key difference now is that Germany has expanded these controls across all its borders.

FILE PHOTO: The German federal police patrols along the German-Polish border area in order to detain migrants from Belarus in Frankfurt (Oder), Germany, October 28, 2021. REUTERS/Michele Tantussi

Germany’s Bid to Curb Secondary Movement, Cut Refugee Benefits

Dimitriadi highlights that Germany’s new policy is not just about security or migration control but also part of a broader plan to cut financial and social benefits for refugees who already hold asylum status in another EU state.

“This is all part of Scholz’s plan to stop financial and social benefits to those who already have refugee status in another state. Germany wants to curb secondary movement. And this impacts Greece because Greece does not offer benefits to refugees,” asserts Dimitriadi.

“This decision will likely impact secondary movement, but it is yet to be seen how. Germany will likely try to coordinate with countries to send people back to where they applied for asylum, but there will be difficulties with this,” she adds.

Moreover, Germany is likely to face logistical challenges in enforcing stringent checks across its extensive borders. Germany might implement random checks or fast-screening, but hard enforcement across all borders seems unrealistic given the nature of travel routes.

The Impact on Europe’s Far Right, Terrorism, and the Domino Effect

“The biggest problem is the political message sent by Germany because it plays into the hands of the far right. Germany is essentially saying ‘we are reintroducing border controls because migration is a problem and the far right is right’. I am not sure how promising it is to take a part of the far right’s playbook. We saw this in the Netherlands, and in France, to an extent. When we play into the hands of the far right, instead of appeasing political extremes, it tends to strengthen them,” warns Dimitriadi.

In fact, many analysts view Germany’s decision as a reaction to its own shifting political landscape, particularly following the recent electoral success of a far-right party in eastern Germany. This victory has forced mainstream leaders to address growing public discontent over migration.

An increase in terrorist attacks across Europe, as well as high-profile incidents like the cancellation of Taylor Swift’s concert in Vienna due to security concerns, has heightened fears and pressured governments to act.

There are concerns that Germany’s unilateral actions could set a precedent for other European countries, undermining EU solidarity on migration and encouraging more nations to adopt restrictive border policies.

“Germany’s decision about borders is less about Dublin and more about a political message. And it sends a broader signal that the Schengen is weak,” warns Dimitriadi. And this last message, may carry with it many unanticipated consequences.

Bjorn Hocke, member of Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) looks on after first exit polls in the Thuringia state elections, in the state parliament building in Erfurt, Germany, September 1, 2024. REUTERS/Thilo Schmuelgen

Mitsotakis Faces Political Headwinds

With Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ party, New Democracy, slipping in the polls and grumblings within the party growing louder, the Greek leader is right to be concerned about the potential impact of Germany’s announcement over borders.

According to To Vima, Mitsotakis has sought to downplay internal party tensions, but he recognizes that appeasing the right-wing elements within his party may become critical in the coming months.

On the foreign policy front, migration will likely feature prominently in upcoming talks between Mitsotakis and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan during the UN General Assembly next week. Greece, which continues to push for stronger European burden-sharing on migration, has already signaled that it will not accept the return of migrants outside the framework of the Migration Pact.