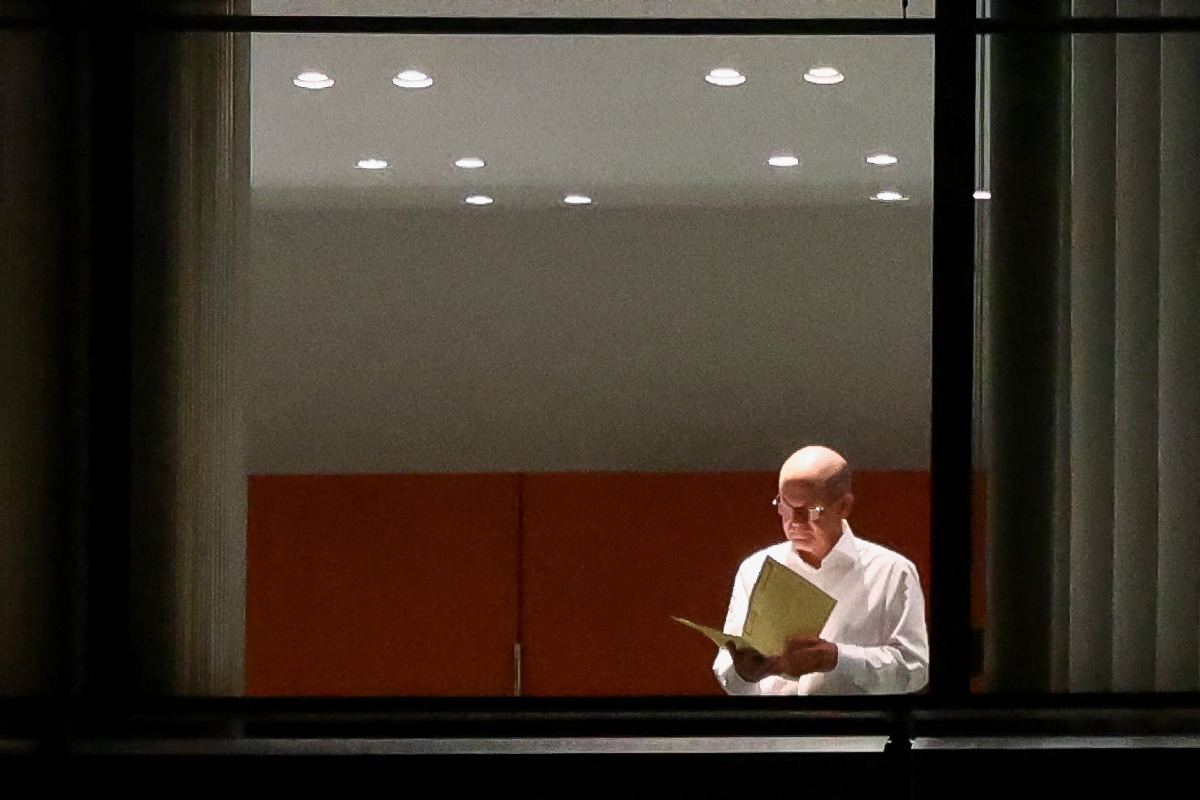

In the end, it was only a matter of when and how Berlin’s coalition government would crumble. Over the past weeks, tensions within the three-party coalition had escalated to such an extent that Chancellor Olaf Scholz saw no alternative but to pull the emergency brake: dismissing Christian Lindner, the finance minister and head of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP).

Known for his measured and moderate tone—some would say uninspiring—Scholz stunned political observers with his sharp accusations against Lindner, including charges of “egoism” and “short-sighted politicking,” which were described as unprecedented in Berlin’s political circles.

At the heart of this rupture, as often in politics, lay a dispute over money. The now-defunct coalition was deeply divided ideologically on fiscal policy. While Lindner and the FDP adamantly insisted on strict budget discipline and adherence to Germany’s debt brake, Scholz and the Greens believed that overcoming Germany’s economic and political challenges required taking on new debt.

The breaking point came when Lindner rejected Scholz’s proposed additional funding for military aid to Ukraine. In summary, a toxic mix of foreign policy and fiscal disagreements ultimately sealed the coalition’s fate. Adding a dramatic twist, the re-election of Donald Trump as U.S. president has injected a new dimension into Germany’s political crisis.

A German proverb frequently quoted during these tense times—“better a horrible end than an endless horror”—captures the mood surrounding this political earthquake. All sides acknowledge that the timing could not be worse for what is Germany’s most severe political crisis in years. Europe, and indeed the entire Western world, needs strong leadership, particularly in the wake of Trump’s return to the White House. Yet, neither Berlin nor Paris seems capable of delivering it.

Both Germany and France, once the strategic axis of a united Europe, now have governments that lack parliamentary majorities. Compounding matters, both countries face a rising far-right that, emboldened by Trump’s decisive victory, threatens the status quo.

Notably, the majority of Germans had hoped for a different outcome in the U.S. elections. According to a recent poll, 83% had favored Kamala Harris, while 71% expressed fears that Trump’s re-election would strain bilateral relations. Those fears have now materialized.

Germany’s political class wasted no time in congratulating the election winner, reaffirming the importance of transatlantic relations—a rare point of consensus. But this partnership faces significant challenges. On NATO and the Ukraine war, Berlin and Trump remain miles apart. Trump’s claim that he could end the war in a day raises fears in Berlin of a dirty deal with Putin, one that disregards both Ukrainian and European interests.

Moreover, Germans are bracing for increased defense spending within the Western alliance, a reality that has already begun to take shape. Yet the greatest threats to transatlantic ties may arise from Trump’s economic policies. His proposal for a 20% tariff hike, if implemented, could deal a severe blow to Germany’s export-dependent industries. Furthermore, there are growing fears that Trump might pressure Europe into supporting even harsher tariffs on China—an economic catastrophe for Germany, which relies heavily on Chinese markets.

Berlin is particularly alarmed by Trump’s plans to lure German companies to the U.S. with subsidies, a move that could cost thousands of jobs and accelerate the already concerning trend of deindustrialization in Germany.

The economic disagreements that tore Berlin’s coalition apart will now dominate the forthcoming election campaign, which has effectively begun overnight. Scholz aims to trigger new elections through a vote of no confidence—a process he is unlikely to survive. The government is planning the vote for early January, paving the way for federal elections in March or April under constitutional rules.

The opposition, however, argues that this timeline is too slow. Meanwhile, the government seeks to buy time to rebuild public trust. Ultimately, the voters will decide who emerges victorious from this political drama. In the interim, pressing global issues will receive only limited attention from Berlin’s political establishment—a steep price for Germany’s current crisis.

Dr. Ronald Meinardus is a Senior Research Fellow at the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP).