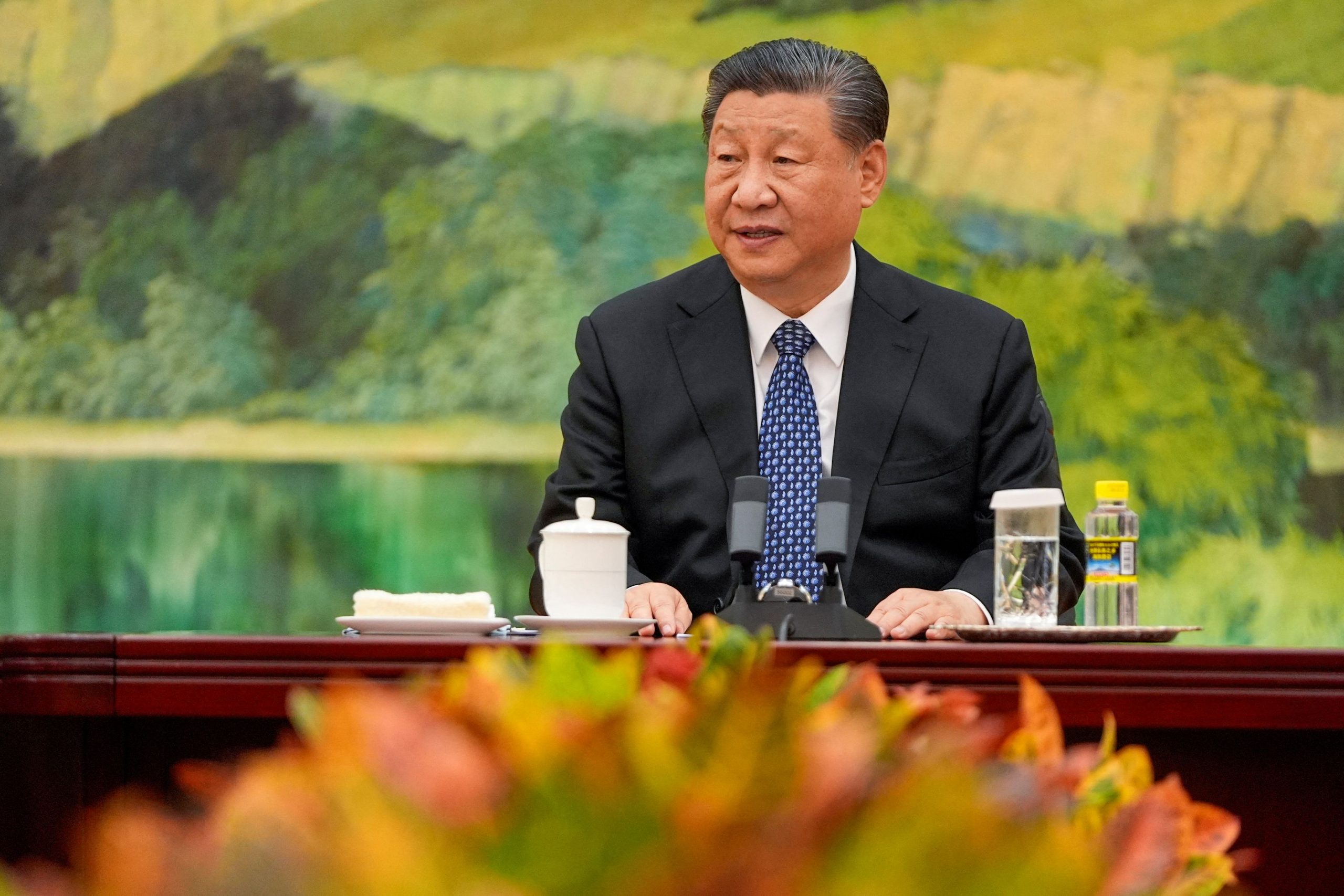

China’s leader Xi Jinping kicks off a six-day trip to Europe on Sunday, his first visit to the continent over the past five years. But he will land in a very different Europe compared to 2019, when he travelled to Italy, Monaco, and France. The highlight of his visit back then was the endorsement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by Italy, which was seen as a major diplomatic success of Beijing. Later that year, Xi’s visit to Greece was also touted by Chinese media as a sign of increasingly close and friendly Sino-Greek relations.

2024 is not 2019

Yet, the mood in Europe is markedly darker five years later. Italy has decided to bid “arrivederci” to China’s emblematic megaproject. The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment signed in-principle in late 2020 has been frozen, amid bitter recriminations and consecutive rounds of sanctions and countersanctions. Tension has been steadily mounting between the EU and China, and the two sides have traded accusations of unfair competition and protectionism.

The glaring trade imbalance in favour of China has triggered a series of EU investigations into a flood of allegedly underpriced exports from the world’s second-largest economy. Beijing was seriously upset by the launch of an anti-subsidy probe into Chinese electric vehicle imports last September and retaliated by opening an anti-dumping investigation into brandy imported from the EU. Last October, the Commission launched a risk assessment in four critical sectors – semiconductors, AI, quantum computing, and biotech – in the context of EU exports to China.

What’s more, the EU has launched additional probes into China’s medical devices and terms of participation in the lucrative European public procurement market in a spate of actions that are further raising tension ahead of Xi Jinping’s visit to Europe. Nor did the recent raids on Nuctech’s offices in The Netherlands and Poland under the EU’s new Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) go down well with Beijing.

But frictions between the two sides are not confined to economic issues. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 poisoned Sino-European relations, as China never really acknowledged its responsibility and opted for a massive Wolf Warrior Diplomacy drive instead. Next, the joint Sino-Russian declaration in February 2022 and China’s disingenuous “neutrality” on Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine also served as eye-openers for many Europeans.

Not surprisingly then, the last EU-China summit in Beijing in December 2023 was marked by undisguised tension on a long list of contentious issues. The European officials stated very clearly that the EU was left with no choice other than making use of its comprehensive set of trade and investment defence tools, but the warning shots were not heeded by Beijing.

Coming from a different China

At the same time, not only is Xi Jinping coming to a different Europe – he’s coming from a different China, too. The property sector bubble that popped three years ago is proving a lasting drag on the Chinese economy. Local authorities, deprived of real estate sales as their key source of revenue, are saddled with mountains of hidden debt. In August 2023, Beijing stopped publishing data about steadily growing youth unemployment rates. Yet another grave problem that Chinese authorities need to grapple with is ageing, now that China has been overtaken by India as the world’s most populous nation on the face of the earth.

The rigidity of Beijing’s zero-COVID strategy further aggravated the economic predicament of the country and the blank paper movement in late 2022 necessitated the authorities’ abrupt about-face. But it would be inaccurate to attribute all the difficulties that China has faced since 2020 to the pandemic or cyclical factors. China’s problems are mostly structural and this casts a shadow over the long-term prospects of the world’s second biggest economy. Inevitably, the slogan about “China’s unstoppable rise”, once a dominant narrative on a global scale, sounds a lot less convincing now.

Despite persistent underconsumption in China and even risks of deflation, Beijing has once again decided to overinvest in manufacturing and exports, i.e. a supply-side solution to a demand problem. In other words, in order to retain reasonably high short-term growth rates, China is exporting its domestic problems to the rest of the world – primarily advanced economies, such as the EU. This is the continent Xi Jinping will visit in a few days.

Xi’s agenda in Europe

The Chinese president will visit France, Serbia and Hungary. The three countries have been carefully chosen – arguably, for a host of reasons, but also on the basis of a clear-cut rationale that aims at increasing China’s influence. France is a major economy and a leading political power in the EU, while Serbia and Hungary stand out as the most China-friendly countries in Europe.

What is likely to happen in France? According to Élysée sources, the French president plans to discuss the wars in Ukraine and Gaza with his Chinese counterpart, though it is debatable what Paris could realistically achieve – Beijing is unlikely to budge on its “no-limits partnership with Russia” and has largely stayed out of the fray in the Middle East.

Economic cooperation will be a somewhat more palatable topic on the agenda of the bilateral talks. During his presidency, Emmanuel Macron has made three official visits to China and the two countries have a number of agreements for cooperation in significant sectors, including nuclear and wind energy. In 2023, the total bilateral trade was worth $76.7 billion, with the balance only slightly in favour of China.

At the same time, Macron has invited Ursula von der Leyen to the upcoming meeting in France. While it is still unclear whether German chancellor Olaf Scholz will also join the party, the French president clearly envisions a repeat of the 2019 format, when Angela Merkel and Jean-Claude Juncker were also present in Paris in a display of EU unity.

Interestingly, the current president of the European Commission is considered one of the EU’s most hawkish leaders on China and is the architect of the bloc’s de-risking strategy towards Beijing. This is why, while meeting Ursula von der Leyen, Xi will have to put on a brave face, given Beijing’s dislike for collective EU institutions and preference for bilateral relations with member states.

In Serbia, Beijing’s “iron-clad friend”, Xi will commemorate the 1999 bombing of Belgrade by NATO. An impressive Chinese Cultural Centre has now been erected at the site of the former PRC embassy, which was also hit by the Atlantic Alliance back then. Therefore, the timing of Xi’s visit is fully in line with both Serbia’s dominant anti-NATO mood and Beijing’s anti-western rhetoric.

The construction of industrial units, motorways, bridges and railway lines financed with Chinese loans and built by Chinese companies will be a prominent theme for propaganda purposes. China’s steadily growing presence in Serbia is warmly welcome by President Aleksandar Vučić, whom the opposition accuses of an increasingly authoritarian course, despite the country’s candidacy to join the EU.

In clearly undercutting Serbia’s European prospects, the government in Belgrade has purchased drones and missile-defence systems from China, as well as Huawei surveillance gear with facial recognition capabilities. In addition, Serbia has recently signed a free trade agreement with China.

In Hungary, China-fuelled investments will no doubt be a big-ticket item. The Chinese president is expected to visit Pécs to announce the construction of a Great Wall Motors electric vehicle factory. This comes on the heels of CATL’s decision to invest in a large-scale battery factory in Debrecen. It is less clear whether the delayed Belgrade-Budapest railway project, already in its second decade, will be much talked-about.

The political connotations of Xi’s presence in Hungary are hard to miss. Viktor Orbán is at loggerheads with Brussels on a number of issues, stays on good terms with Moscow and has consistently objected to western support for Ukraine. Once again, timing matters: Xi’s visit takes place a few weeks before Hungary undertakes the rotating EU presidency starting next July.

Not least of all, through his visits to Serbia and Hungary, Xi seeks to demonstrate that China remains influential in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), despite the lackluster performance of the China-led format once known as 17+1. Notably, Greece joined this club in 2019 for no comprehensible reason. After the walk-out of the three Baltic countries in 2021-22, the grouping has now shrunk to 14+1, and Belgrade and Budapest are the only remaining CEE capitals genuinely keen on their close ties with Beijing.

Partner, competitor or systemic rival?

In the West, Xi’s visit to Europe is seen by many as a mission to drive a wedge between the US and the EU, as well as to stress inherent divisions within Europe. The Chinese president’s itinerary shows that Beijing is aware of the deterioration of Sino-European ties and seeks to boost cooperation with China-friendly countries. Yet, over the past few years Europeans have developed a much more clear-eyed and assertive approach to China, for three main reasons.

- First, China’s has been demystified in many ways. It now has a lot more wrinkles on its erstwhile radiant face, and is no longer seen as an ever-rising crisis-free powerhouse.

- Second, by supporting illiberal regimes around the globe, starting from Putin’s Russia, China has shown its true colours and can no longer claim the status of a benign peace-loving power.

- Finally, back in 2019 the EU defined China as a partner, competitor and systemic rival at the same time. While partnership is definitely needed with a view to addressing global challenges, e.g., the climate crisis or public health, the needle is inexorably moving towards the competition and rivalry components.

* Head of Asia Unit, Institute of International Economic Relations (IIER), Athens, Greece