Recent polling in Greece reveals that disappointment, anger, and fear dominate public sentiment, with only a tiny minority retaining any sense of optimism and hope. Coupled with an historical low in public confidence in the state and the judicial system, it is tempting to interpret these findings as a dire reflection of a society trapped in yet another crisis—though this time, it is not economic, but a deeper crisis of public trust. However, rather than viewing the current collective despair as an ingrained national trait, it might be more productive to approach it as an expected consequence of systemic failures, political disillusionment, and an enduring sense of abandonment.

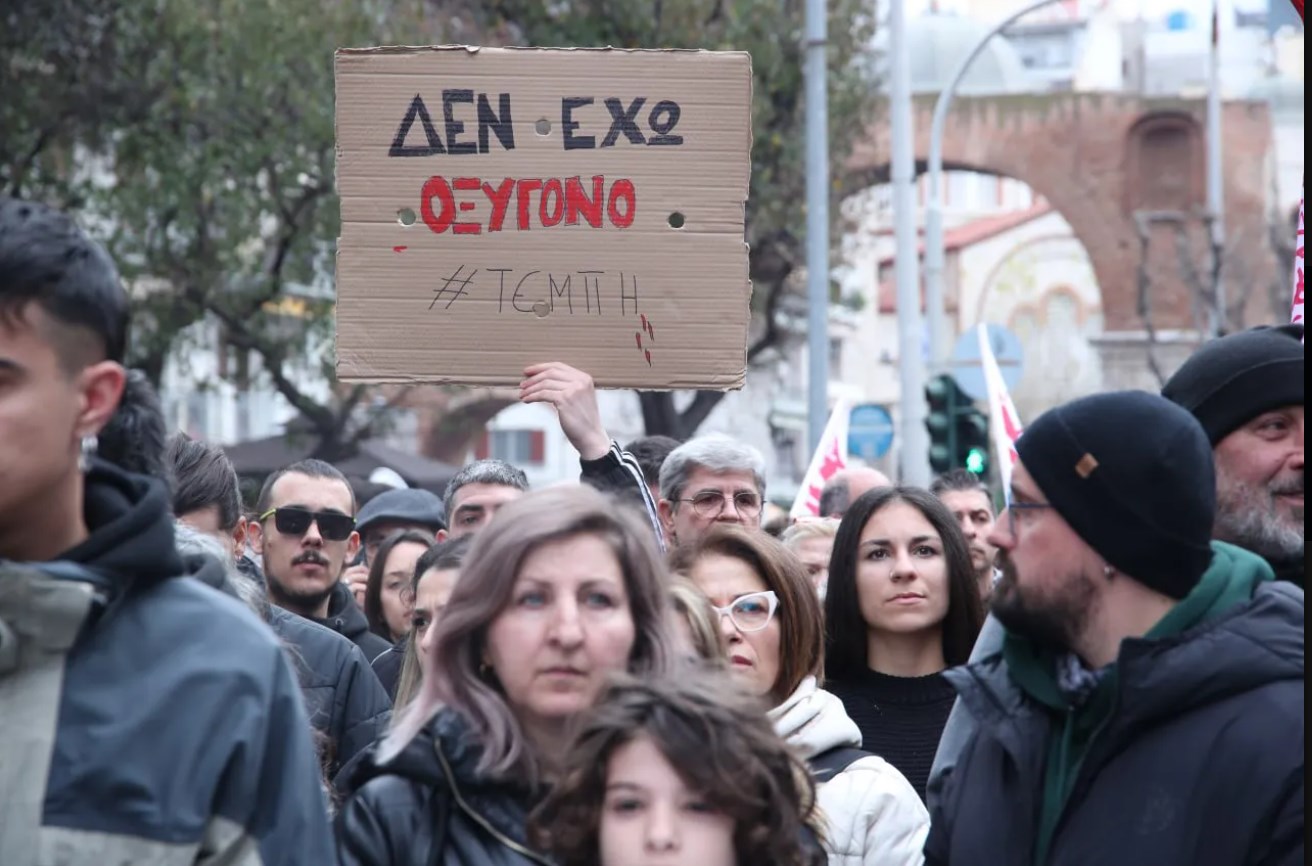

Nowhere is this dynamic more apparent than in the wake of the Tempi train disaster, a tragedy that exposed the state’s chronic neglect of public infrastructure and accountability. On February 28, 2023, two trains collided head-on in central Greece, killing 57 people—many of them young students returning from holiday. The catastrophe sparked one of the largest waves of public protests in recent years, with tens of thousands demanding justice, transparency, and systemic reform. More than a failure of governance, the fatal accident laid bare a breakdown in the social, political, and institutional structures that aim at safeguarding human lives and advancing well-being.

The public outrage that followed was not just about railway safety or bureaucratic inefficiency. It revealed a deep-seated erosion of people’s trust in Greece’s governing institutions. Citizens have long felt positioned as passive subjects of neglect, rather than active participants in a system of democratic care.

The Politics of Care

Traditional political discourse often approaches crises in binary terms—blame versus denial, reform versus inertia. However, as Dr. Anastasia Kavada, Reader in Media and Politics at the University of Westminster, argues in her latest work on the “caring public sphere”, an alternative framework is possible—one in which care is redefined as a civic and political imperative.

Care, in this sense, is not just limited to personal compassion or welfare policies. Rooted in feminist political theory, such as the seminal work of Joan C. Tronto, it is a foundational principle for democratic engagement, emphasizing shared vulnerability, mutual interdependence and responsibility, and the necessity of institutions that actively nurture public well-being. Kavada contends that crises—whether economic, environmental, or social—can be understood as crises of care, where the failure to “care well” for people, infrastructure, and public goods leads to societal disintegration.

Applying this lens to Tempi, we see that the tragedy was not merely the result of outdated railway systems or human error. It was the culmination of a decades-long erosion of care in public governance—the normalization of indifference to systemic risks, the prioritization of private over public interest, and the persistent exclusion of citizens from meaningful democratic deliberation.

Reclaiming the Public Sphere as a Caring Space

Public discourse following the Tempi disaster has largely been shaped by anger, resignation, and a familiar cycle of political blame. However, a care-based approach offers a different path—one that moves beyond reactive outrage to cultivate an engaged and responsible public sphere.

Following Tronto, Kavada emphasizes that recognizing shared vulnerability is crucial for fostering political solidarity. Accordingly, care can be a critical lens to understand whose vulnerabilities are privileged over others, whose needs are prioritised, as a way of identifying and addressing inequalities in how the state cares for people and infrastructure. The grief over Tempi should thus evolve from an isolated emotional response to a collective demand for a system that prioritizes care—for safety, transparency, and public infrastructures.

In Greece, political discourse is often dominated by rhetorical battles rather than genuine engagement. Care, however, demands active listening—not just from authorities, but among citizens themselves. Survivors’ testimonies, the demands of the victims’ families, and the voices of railway workers who had long warned about safety risks should not be absorbed as fleeting media moments. They must become the foundation for policy change and democratic accountability.

Notably, democratic care extends beyond human relationships to the physical and technological infrastructure that enables social life. The failure of the Greek railway system is not just a failure of engineering; it is a failure to maintain and protect the commons—to care for the very structures upon which public safety depends. Investing in infrastructure is not merely an economic or technical decision; it is a moral obligation to future generations.

Care as a Force for Structural Change

A shift towards a caring public sphere requires more than symbolic gestures of reform. It demands a redefinition of political responsibility—one where care is embedded in governance, civic participation, and policymaking. Kavada suggests at least three domains of action for structural change.

The first focuses on the potential of citizen-led care initiatives. Public engagement cannot be confined to elections and protests. Local assemblies, citizen-led safety audits, and participatory budgeting processes can become core mechanisms for ensuring that care remains at the centre of governance, be it local, regional, or national.

Second, there is a need for expanding the meaning of public deliberation. Care-based democracy recognises that deliberation is not just about rational argumentation but also about emotional processing, personal testimony, and ethical responsibility.

And finally, the way accountability is understood and practiced by governing bodies and organisations should extend from a solely legal and often bureaucratic exercise to institutional commitment to care—a proactive duty to prevent harm and nurture public trust through the fair allocation of resources to care for people and public infrastructure.

Towards a More Caring Greece

The prevailing atmosphere of disappointment across Greek society should not be dismissed as an insurmountable darkness but recognised as a plea for a new social and political vocabulary—one that centres on care, mutual responsibility, and a determination to co-create a better future for all.

Feminist political theory reminds us that care is both a practice and a disposition. It is enacted through policies, public investments, and daily civic interactions. If Greek citizens are to move beyond the current cycle of despair, they must reclaim care as a fundamental democratic principle, shaping not only how we grieve and protest but how we govern and rebuild.

The Tempi disaster should not become just another national tragedy, absorbed into the long list of systemic failures that fade from public consciousness. Instead, it should serve as a turning point—a moment to recognise that despair is not an endpoint, but a signpost toward collective renewal.

A more caring Greece is not an abstract ideal. It is a viable choice for reimagining a better future.