Long gone are the days when the EU and China indulged in pleasantries about each other as key partners, by downgrading their differences as to the form of government, human rights or geopolitical outlooks. Ironically, while the two sides have hit record-high levels of bilateral trade and interdependence, Sino-European relations have become markedly fraught with disputes and political tensions.

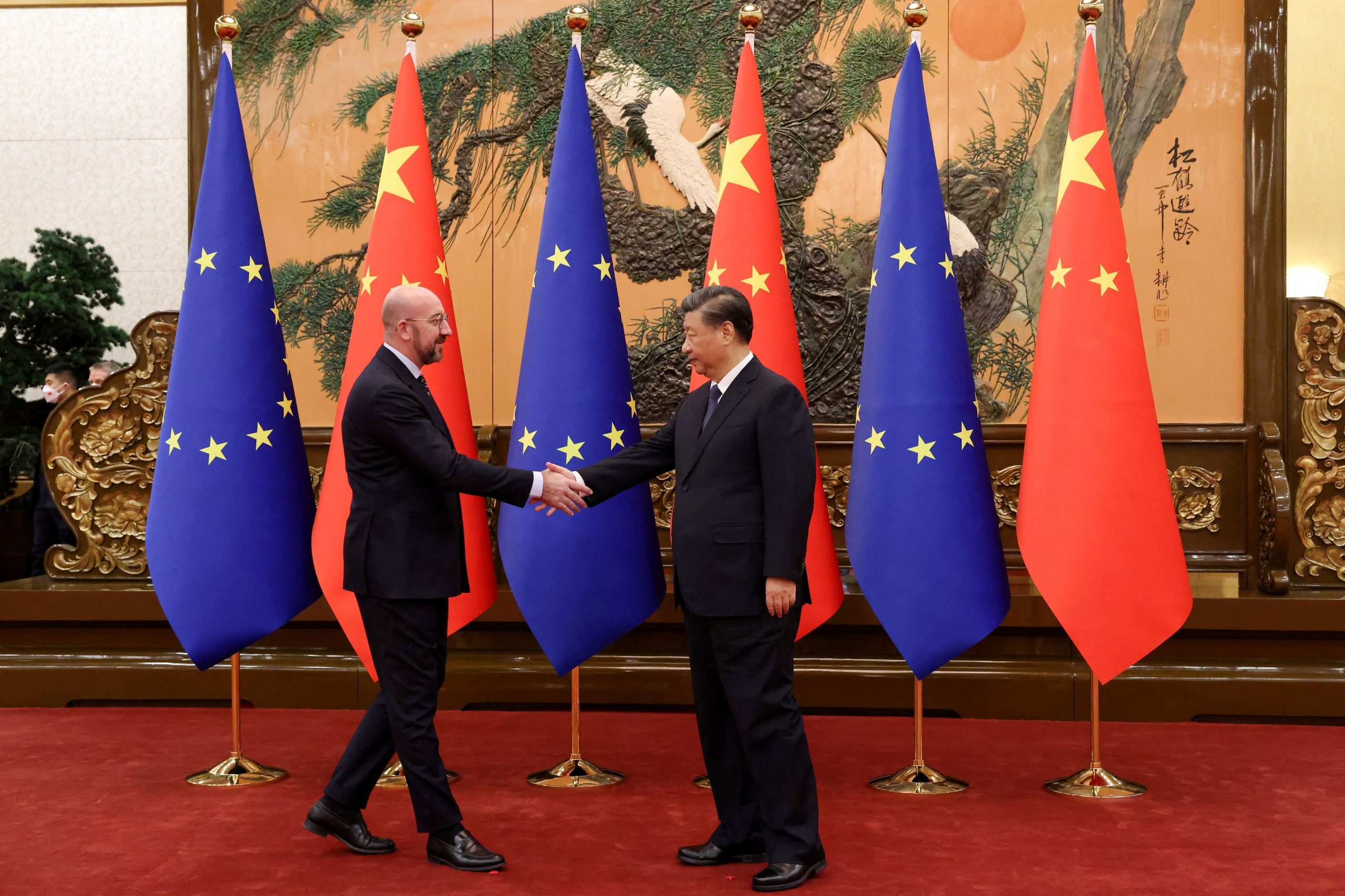

The complexity of this relationship will be on full display on 7-8 December, when Chinese and EU leaders meet in Beijing, the first summit held in four years under this format. The talks will by no means be an amicable sit-together and risk injecting additional tensions into close, yet increasingly strained, relations.

Notably, the release of a joint statement will be a seen as a surprise, as the gathering may well lay bare deepening rifts between the two sides.

Reciprocity – the elephant in the room

The glaring trade imbalance in favour of China is an obvious point of friction. Bilateral trade in goods in 2022 rose by 23% year-on-year to €857 billion. The EU’s trade deficit also reached a whopping €396 billion, a 58% increase from 2021.

Investment has been an equally contentious issue. The much talked-about Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) was signed in late 2020, but has been frozen since the two sides traded a salvo of sanctions and countersanctions in early 2021. This didn’t come as a bolt in the blue.

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), an influential think tank, pointed out as early as 2016 that “Chinese firms can buy top European companies, such as Volvo, Pirelli, or Syngenta, [while] European firms cannot do the same in China”. In a similar vein, one could pose the rhetorical question whether European operators are allowed to undertake the management of Chinese sea ports, just like COSCO has done in Piraeus, Greece? Obviously not.

European investors in the Chinese market are facing a mountain of hurdles, as repeatedly pointed out by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. Its latest annual position paper highlights a slew of measures that have been imposed by Beijing, and have “deepened uncertainty and raised compliance risks”. Tellingly, the document puts forward more than 1,000 recommendations, but few are expected to be taken on board by China.

Europe’s response

Authorities in Beijing are accusing the EU of what has been – and continues to be – their own unfair practice ever since China joined the WTO in 2001. Hence the ever-growing raft of EU defence tools, which includes a set of anti-dumping measures, an inbound FDI screening framework, an anti-coercion instrument which came about as a response to China’s economic pressure on Lithuania, an international procurement instrument, a toolbox for 5G security, etc.

Notably, there are other defence tools in the EU pipeline, such as a far-reaching economic security strategy, an anti-forced labour instrument, a critical raw materials act, a security-related control regime for outbound investments by European companies, etc. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which has left Beijing fuming, is already enforced in its transitional phase.

And the EU defence toolkit is set to become even larger than that. For instance, the European Parliament has recently released a report on Chinese investments in European maritime infrastructure and is calling on the Commission to launch a process for the adoption of a comprehensive European port strategy.

It is against this background that last October Brussels launched an anti-subsidy probe into China’s electric vehicle sector, blasted by Beijing as “protectionist” and “jeopardising the country’s rights”. No doubt, this will be a key battleground during the upcoming summit.

Intensifying competition and even rivalry

Meanwhile, the scope of Sino-European disputes goes way beyond trade and investment. China’s technological support to Russia for the war in Ukraine is yet another sticking point – and a big one, at that. Thus, Brussels is eyeing Chinese companies that are allegedly flouting EU sanctions.

Last June, three Chinese entities were included in the list, and it’ll be interesting to see the content of the upcoming 12th round of EU sanctions. No wonder then that the Brussels needle on Sino-European relations has moved towards the “competition” and “rivalry” components of the EU’s 2019 composite definition of China, “partnership” being the third one.

For the time being, the primary concern of Europeans relates to their dependency on China. But dependency cuts both ways and China also relies on the European market to a large extent. This explains why Chinese authorities, which are battling an economic slowdown, are visibly jumpy and read into de-risking as being tantamount to de-coupling. And this also shows that the EU leaders could be a lot more confident and assertive when they meet their counterparts in Beijing.

*Plamen Tonchev is Head of Asia Unit Institute of International Economic Relations (IDOS/IIER)