The lecture, titled “Facing down the furies: How the ancient Greeks can help society address the problem of suicide,” will take place at Deree – The American College of Greece on Tuesday, January 30 at 7:00 pm. It precedes by a few weeks the March 19 publication of Hall’s latest book “Facing down the furies: Suicide, the Ancient Greeks and Me.”

Admission is free of charge and open to the public, but registration is required.

Dr. Hall, a professor of classics at Durham University in the United Kingdom and a member of the British Academy, is one of the world’s most distinguished figures in her field. She has written dozens of books and articles about the history, society and thought of the ancient Greek and Roman world.

With a painful flashback to her own family’s experiences, Dr. Hall parallels her family’s struggle with suicide with that of characters from Ancient Greek tragedy. She shares how these ancient works provided her with wisdom and comfort, guiding her through the maze of guilt and grief and offering hope in the midst of immense personal challenge.

A few days before her arrival in Athens, Dr. Hall shared with ToVima.com some of her thoughts on the matter:

On how ancient Greek tragedies, such as those of Sophocles, can offer wisdom and comfort to people struggling with similar trauma, and how they helped her deal with her own experiences:

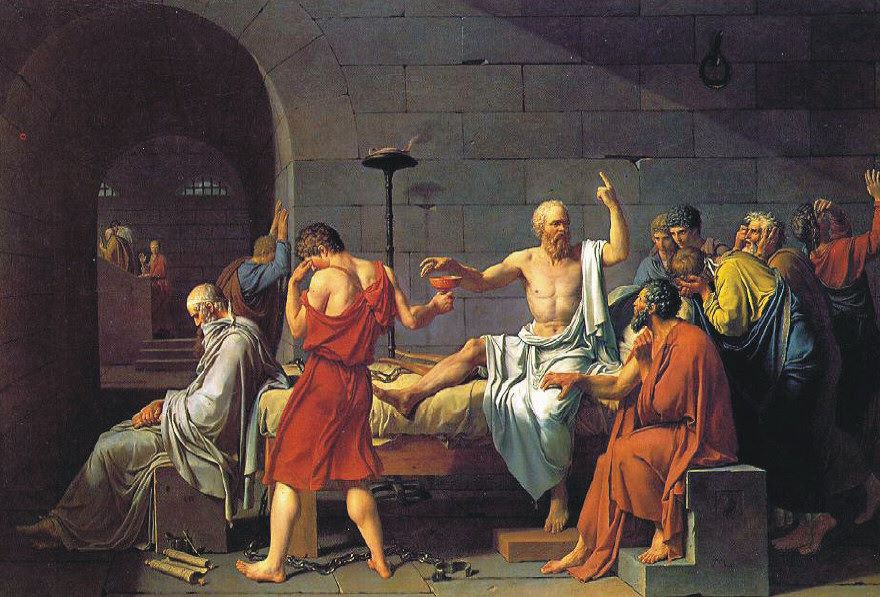

Until very recently, there was a huge stigma attached to suicide. It was proscribed by Christianity and actually illegal in some jurisdictions, punishable by refusal to give the corpse burial and confiscation of the deceased’s estate. Such literature as did address suicide was always focussed on the individual with self-destructive motives. But Greek tragedy explores in emotional depth and detail the impact of suicide on the bereaved—parents, children, friends, colleagues, the wider community. Greek tragedy does not pass moral judgement on those in despair contemplating suicide, but portrays them thinking through their (limited) alternatives, expressing their rage and pain, and describes suicidal acts with the greatest pathos. In my own maternal family line, repeated suicides have had a tragic impact over three generations. I have found that reading Greek tragedy has provided answers to the moral questions raised by suicide and huge comfort in its tender scenes of desperation. I wish my great-grandfather, my grandmother, my mother and her cousin, as well as all their relatives, could have read these texts alongside me. Sophocles’ Ajax is a case-study in how not to handle a desperate man; Euripides’ Heracles is a case-study in how to support a man intent on self-destruction and save his life.

On the parallels between the psychological damage caused by suicide and the ancient Greek idea of the family curse, and how she sees this connection in the context of modern society:

The ancient belief was that the gods would eventually make families pay if one of their members committed an atrocity, even if the reprisals took generations to be carried out fully. But in Agamemnon, Aeschylus uses several different ways to present the actual form taken by this kind of curse. In Agamemnon, the king’s downfall is caused specifically by the working out of the curse, sworn by Thyestes at the infanticidal banquet, against the offspring of Atreus. The chorus believe that it is not affluence itself which causes the destruction of a household (a traditional and widespread view), but a single iniquitous deed. The evil deed begets more evil deeds, in breed like itself (763–6).

There can be no clearer statement that the miseries of a household are the direct result of former felonies. Bad behaviour begets bad behaviour, inherited by each child of a cursed family from its cursed parents. While the idea of an inheritable curse may seem superstitious, alien and primitive to us, it is worth thinking in terms of modern theories about the adverse effects on children of bad parenting and of poor parental examples. Dysfunctional families do often produce dysfunctional children, who reproduce, when they become parents themselves, the maladjusted behaviours of their own inadequate parents. Taken from this perspective, the archaic concept of the inheritable curse may not seem so bizarre after all. It is now known that there may even be a physically inheritable dimension to the specific tendency to suicide. It consists of DNA variations in a region of the genome on chromosome 7. As a teenager, I tried to understand what had happened in my mother’s family line in terms of all these models. Perhaps a depressive strand of DNA has been inherited down the generations. Presumably neither my great-grandfather nor my grandmother had enunciated a formal curse. But who knows what cruel words may have been said to or by them which helped to seal their fates and make the consequences of their fates for others unavoidable? Words said by my grandmother to my mother certainly damaged and wounded her; words said by mother to me made it difficult for me to feel I was not somehow implicated in her mother’s suicide, despite being three and a half when it happened.

Edith Hall’s lecture is held as part of the annual lecture series of the American College of Greece – Deree in honor of statesman Eleftherios Venizelos, with whose intervention the school was re-established in Greece after the Destruction of Smyrna in 1922.