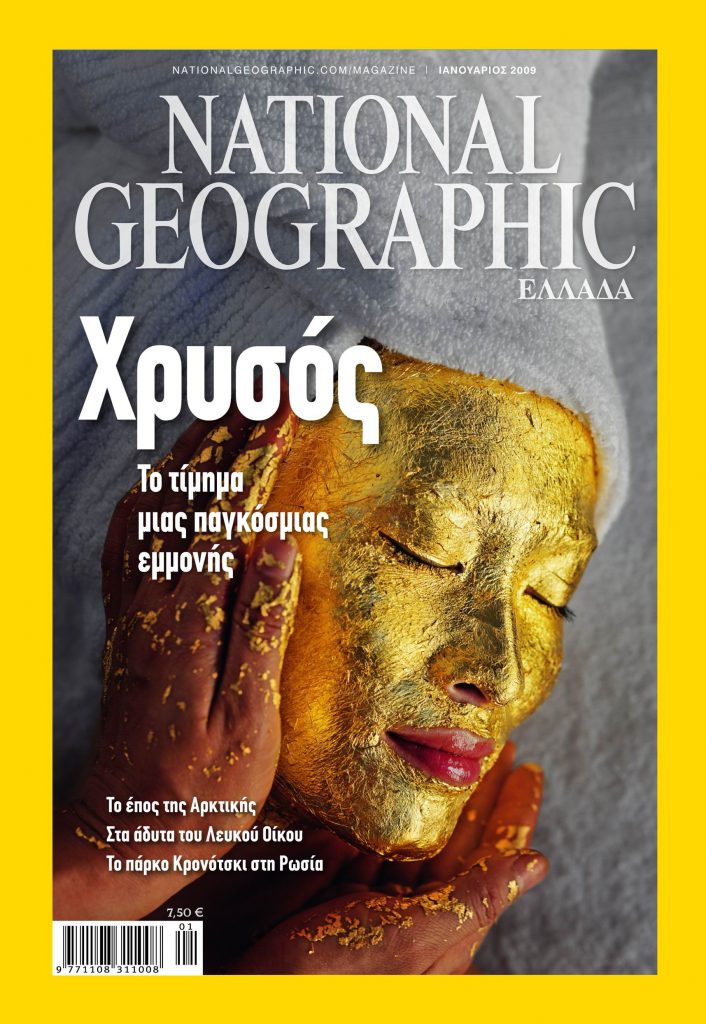

There was a time when print magazines held an irreplaceable spot in the lives of millions. These publications were not just monthly reads, but, rather, cultural touchstones, with their pages offering a window into the vast wonders of the world. However, it is clear that the golden age of print is rapidly fading, leaving behind a profound sense of nostalgia and a stark reminder of how quickly empires can crumble. Look no further than National Geographic.

For decades, the magazine was synonymous with high-quality journalism and breathtaking photography. Millions of people around the world subscribed to the journal, its iconic yellow border promising readers an adventure with every issue.

Fast forward a few decades, and Disney+ takes over the ropes in 2019. In 2022, the magazine let go of six editors, focusing the cuts on long-form journalism, science, and travel—core elements of the brand’s identity. By June 2023, all remaining staff writers had been dismissed, with the magazine from then on relying entirely on freelancers.

“The rise and fall of the National Geographic (NatGeo) brand provides an illuminating case study in how media empires are destroyed,” comments Ted Goia, music and literary critic and author of 12 books.

The trend does not stop at the journal’s yellow borders, however, but extends to most of the legacy media.

Reader’s Digest, once the most circulated magazine in the U.S., filed for bankruptcy twice, in 2009 and 2013. Life magazine ended its regular print editions in 2000, and Ladies’ Home Journal followed in 2016. American Heritage, once a platform for Pulitzer Prize-winning historians, released its last print in 2013. Even The Saturday Evening Post, still in print, has seen its circulation plummet by 95% from its peak.

“Publishers, brace yourselves—it’s going to be a wild ride,” Matthew Goldstein, a media consultant, wrote in a newsletter in January.

Magazines that once thrived on their ability to offer in-depth, well-researched articles are now struggling to survive in a world where short-form content and social media dominate.

Brian Morrissey, media analyst and writer of “The Rebooting”, takes a similar view, arguing that the dawn of the digital era will turn legacy media into “a different industry, leaner and diminished, often serving as a front operation to other businesses.”

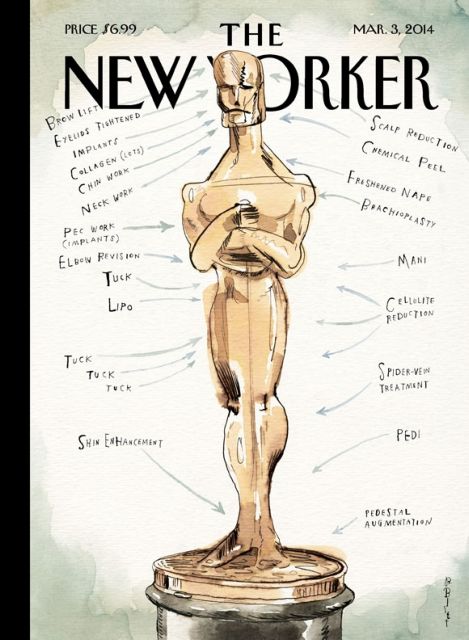

Indeed, in an effort to stay afloat, print media are now focusing their efforts on expanding their offerings beyond traditional news coverage, to include videos, entertainment, and interactive content among others.

“The legacy outlets are all chasing short-form ‘content’ (ugh!) now, and have lost confidence in good writing,” Goia observes.

For example, in addition to its news coverage, the New York Times now has a cooking app, a series of games, and a product-review website called the Wirecutter. “It is not so much a newspaper as a digital lifestyle brand. turning itself into a lifestyle brand,” says New Yorker writer Claire Malone.

Even rebranding strategies have their pitfalls, however, as the newly reinvented news media end up directly competing with entertainment media for customers’ subscriptions, often being the first to be cut when the monthly aggregate gets too expensive.

The “death” of legacy media seems inevitable, says Goia, who argues however that their imminent extinction doesn’t mean the end of journalism altogether. He insists that we must not waste too many tears on the matter, but should work towards “building something solid to take their place.”

“The crisis is here,” Malone concurs. “It needs solutions if we’re going to keep recommending, in good conscience, that promising young talent join the media’s ranks.”