By Marilena Astrapellou

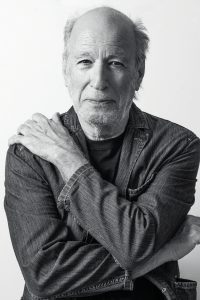

He once wanted to be a ship captain. He spent a summer working on the ship “Kythera” at the age of 16, but he did not last long in the profession. “My grandmother cried, she was afraid I would drown, and because I loved her I didn’t want to upset her,” Nakis Panayotidis says with the humorous and slightly self-deprecating style that distinguishes him. There was nothing to worry about anyway. The path he followed illuminated his journey to places inhabited by fascinating people -without the risk of “drowning”. Always looking for experimentation and the use of unusual techniques and materials, diving into the ‘unknown’ with disregard for risk, he created works of a completely different nature – three-dimensional sculptures and installations, textural images – drawing inspiration from antiquity to the modern era.

His love for the sea never faded. It is probably no coincidence that in his retrospective exhibition currently hosted at the Museum of the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation entitled “Shut your Eyes and See” you are greeted by a large black and white photograph of a sea horizon – because he also created large-scale photographic installations – which he illuminates with neon to highlight the invitation for both physical and philosophical contemplation. Moreover, as I call him to talk through a phone app, I from Athens and he from his home in Bern, where he has been based for decades, a tiny photograph of him appears, showing his younger self performing an impressive dive in the waters of the island of Hydra.

Talking with him is a pleasure. It’s very easy to get on the first person, as he encourages you to do, and listen to stories of a full life, which he has lived for 77 years without a trace of seriousness. Nakis Panayotidis was born and raised near Fokionos Negri and Agias Zonis in Kypseli, but he would meet his destiny in Italy, especially in Turin, where he went to study architecture. “I was interested in automobile design and I found out that in that city’s Architecture School there was such a department, in fact Batista Pininfarina taught there. I was also obsessed with architecture because I really liked linear design, and at the same time I felt that somehow I had to satisfy my parents’ expectations.” Although he made it to the fifth year, as he will say, he did not complete his studies: “I realized that in this field progress was very difficult, that I should probably become an employee of some architect and also of the clients. The freedom that I have in me, the free spirit that I maintained and still maintain, did not let me take that direction.”

The Italian influences

Self-taught, but with decisive influences from his studies. For example, architecture greatly influenced his early, minimalist, works, with just three colours, red, blue, white and with material “completely arte-poverist”, small sticks like toothpicks, crushed in the middle to create shadows, which he presented in the mid-1970s. During his studies he came into contact with the Arte Povera artists through the Christian Stein gallery in Turin, where they essentially began their career. “The first exhibition was organized in Bologna by Germano Celant, who also named the movement, drawing inspiration from Jerzy Grotowski’s “For a Poor Theatre”, Panayotidis explains and continues: “There I immediately met all the artists. The ones closest to me were Mario Merz and Alighiero Boetti, Gilberto Zorio, but also Michelangelo Pistoletto. Of course, I had one foot in and one foot out. I saw how they worked but I started with my own style.” Because, of course, in Italy the exhibitions held and the artists that were active, like Enrico Castellani and Lucio Fontana, made a deep impression on the young Panayotidis. “I was shocked when I first saw Fontana’s works!” he says with an admiration that seems to have not faded even today.

In 1968 he decided to come down from Turin to Rome to study Fine Arts and Cinema: “I didn’t like Rome. It was like seeing Fokionos Negri but without its humanity. For me the whole city was a lie, even though I met wonderful people there. I preferred Turin, you can’t easily leave that city.” At that time, Yannis Kounellis and Mario Stifano were in Rome. Panayotidis was in contact with the other Greek immigrant artist, as much as his distant psyche allowed. “Kounellis didn’t want to associate with Greeks,” he says.

Free spirit, unconventional artist

Apart from showcasing his works abroad he also presented them in Greece, at the Contemporary Printmaking in Kolonaki in the 1970s, upon the recommendation of Opy Zouni. They were a hit. The buyers included the diplomat, art historian and art critic Alexandros Xydis and Dakis Ioannou: “They were works that received very good reviews and were sold both in Greece and abroad. But I was not interested in either, I was bored. So I deliberately entered a period of crisis. Michel Foucault said that the most important period of an artist is that of a crisis, as long as it is voluntary. That’s what I did.” Panayotidis never wanted to fit into a mould, to join a category, a movement. His indifference to technique was always a conscious choice: nothing would stand in the way of his personal, unconventional vision, nothing would limit his revolutionary spirit. “Being an anarchist and liberated, I am not interested in being known, in being recognized by my previous work. I am always in search of a new visual and plastic principle.”

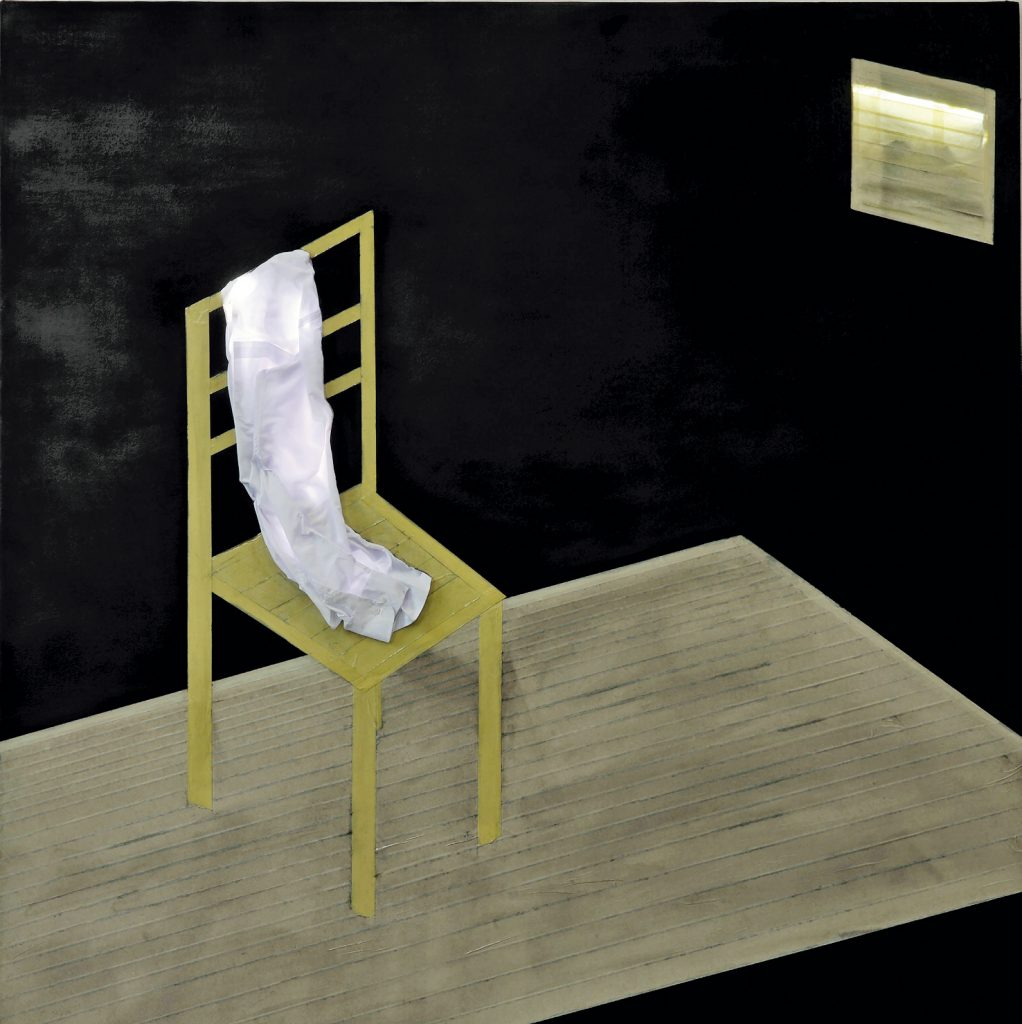

He recounts how in 1977 he found himself at the Centro Internazionale di Sperimentazioni Artistiche Marie-Louise Jeanneret in Boissano and began to abandon his first idiom and search for new materials. “The first thing I got my hands on was pitch paper, which I started to burn and saw that a black glowing shape was forming. In the 1980s I also started using stones, Parisian pavé and photography, first on paper and later on canvas. At first my ‘palette’ was very dark.”

The Greek DNA

Light, or the lack of it, has always shaped Panayotidis’ work. “I am not a colorist. My view is that Greeks have so much light that we don’t need to express ourselves with colour. I think that we, artists like Kounellis, Takis, old Choklis, we didn’t use colours. That is my opinion“. Panayotidis often quotes the philosopher Zan-François Liotard who said that “artists do nothing but go back to their childhood or even their infancy”: “I think it’s true, at least as I understand it. I must confess that I had a very nice childhood. I remember that when I set out from Kypseli to go to Piraeus to swim, at the only indoor pool that existed at that time at the Cadet School, I took the trolley, then the electric train and walked to Hadjikyriakeio passing through the Trouba neighborhood. There you could see through the windows a lamp, a hanging light bulb, a table and a few chairs.

I transferred this image onto the tar paper with my own materials. We artists cannot escape our origins. My work emerges from memories which I don’t seek, they come to me automatically. I have had empathy since childhood, I saw poverty all around me, I did not pass it by. When I arrived in Turin by train I had 6,000 drachmas in my pocket to last me three months. Within two weeks I had no money, I had lent it here and there. This empathy drives the work I create, to document what I have experienced. This is a self-analysis that I’ve been doing for many years now, looking for the ‘whys’ in my work.”

So I suppose his interest in Greek myths and philosophy, especially that of Epicurus, is to be expected: “Philosophical ideas are timeless. For us, who grew up with hippism, Epicurus was a father. Nowadays, Epicurean philosophy is interpreted as well-being, drinking the best wine, smoking the finest cigar, but I don’t think that was the truth that Epicurus was looking for. He was looking for a simple, pleasant and friendly life. I have done works in which I have included Epicurean aphorisms. Well, those aphorisms are modern. And as far as myths are concerned, for me they don’t represent something old, they are a reference to our future.”

Visual Athens today

How does he see the present of Greece and Athens? “What is happening in general, this ‘dubaism’ in architecture, doesn’t resonate with me. But in Kypseli, as well as in Pagrati, I see a substantial life, I find people who communicate with each other. I don’t want to say that Greece has become Berlin, because I wasn’t interested in Berlin either when it was at its peak, 20-25 years ago, and it turned out to be a lie. Germany is not Berlin, but Cologne, Düsseldorf and Munich. Athens has an artificial sense of art production. Everyone seems to be an artist. There are countless theaters and TV series. You don’t see this excess elsewhere, it’s more concentrated in other countries, if I can talk about Italy, France, places I know. I won’t talk about Switzerland, in the field of contemporary art it is the first country in the world. I live in Bern, a city of 140,000 people, and I’ll just tell you that it has a museum designed by Renzo Piano (Zentrum Paul Klee), a Museum of Modern Art that is the oldest in Switzerland, and the Kunsthalle, which has presented all the change in contemporary art. In Greece there are many remarkable artists in all fields, but there is no system to help them. That’s why everyone is trying to find their way on their own.”

INFO: “Shut your Eyes and See” – Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum (13 Eratosthenous Street, Athens), until March 2, 2025. Curated by Fleurette Karadontis, President of the Board of Trustees of the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation, and Matthias Frehner, Former Director of Kunstmuseum Bern.