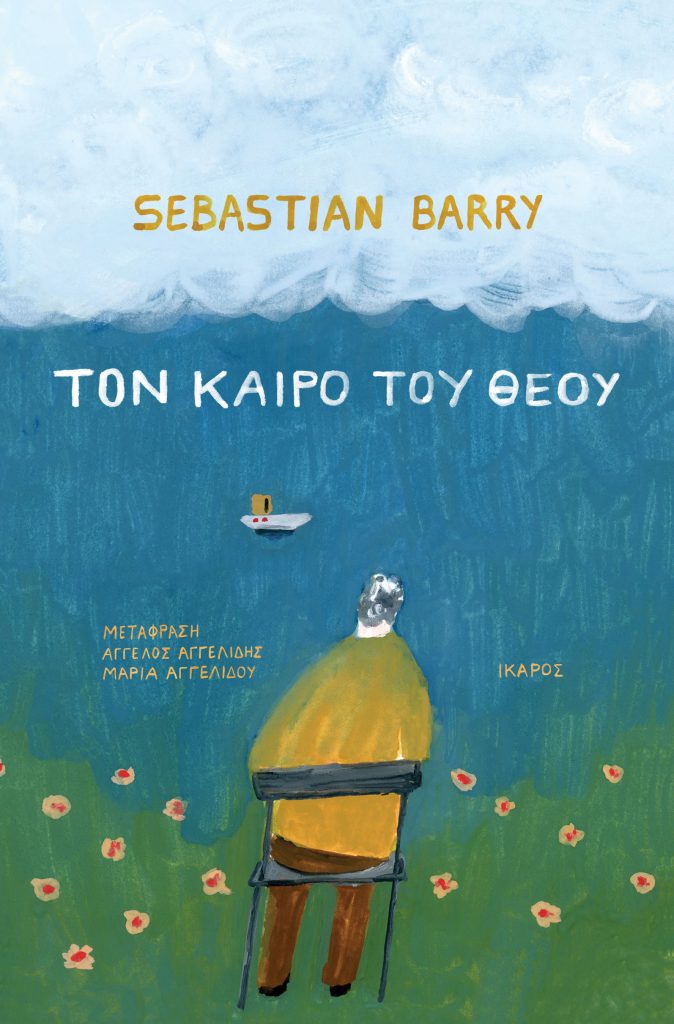

One of the most notable Irish novelists –but also a playwright and poet-, who has twice won the Costa book of the year (for his novels “The secret scripture” and “Days without end”), talks about his latest novel “Old God’s time”, translated recently into Greek (Ikaros Publishing, tran. Aggelos Aggelidis, Maria Aggelidou). A murder investigation leads a retired policeman to confront his past in a stately, often dreamlike novel about the impact of trauma on memory.

Abuse on the hands of the Catholic Church and Magdalene asylums seem to be a recurring trauma which Irish novelists and cinematographers work through. Is it something that the Irish society learns to discover during the last years or was it always so deep in its collective memory?

Yes, always deep in the collective memory, but also sometimes too deep for excavation. Recently I wrote a story about a man propositioning a young boy at a deserted tennis-club. It is based on an actual memory and to this day I don’t what the man intended to do, because I ran away. But the bitter truth is, I could never run far enough, and home was reachable but also problematic and even perilous. It shocks me now to think about the very widespread and therefore ordinary dangers of being a child in Ireland in the 60s. A few of the priests at my school were deeply suspect. Where was innocence to flourish? And then, reading the many survivors’ accounts for this novel, I couldn’t help but feel a definite affinity with them, not least Peter Tyrrell, who wrote Founded on Fear, who eventually killed himself on Hampstead Heath, despairing of comfort and understanding. He describes in forensic detail what happned to him in a terrifying place called Letterfrack.

“Girls fleeing from laundries, children fleeing from orphanages, all had to be returned” Tom recalls.Why there was such apathy and indifference towards Church tactics, at least until 1990’s?

One of the startling anomalies about sending children to institutions was, there was no law on the statute books that said this could be done, it was a normalised societal agreement. Yet the courts sent children away, the Irish police were fully involved in it, and if a child managed to run way, a policeman would bring him or her back, often to endure unfettered punishment that would remind you, incredibly, of the punishment of slaves in the Deep South. Occasionally children seemed to be beaten to death and how easy it was to cover that up, because nobody was in the business of caring. The people who were supposed to be protecting you as a small citizen, the priests, the nuns, the judges, the police, were instead your betrayers.

There probably was apathy, but also, tragically, tragically, collusion. Priests were considered special holy men, and many fathers dumped out their pregnant daughters with the assistance of priests and nuns. When you stare into this abyss of behaviour, there is nothing Christian or Catholic about it. Irish people prostrated themselves at the feet of clerics, they could literally do no wrong. My own cousin, James Dunne, auxiliary bishop of Dublin, was the right hand man of John Charles McQuaid, who for Tom Kettle is some species of devil. I became aware of this when reading the reports on clerical abuse – there was his name, my own DNA, right at the heart of the horror. That can give a writer an almost unstoppable wish to be clear, to be honest, even to try to make amends in a scenario where amends cannot be made.

One can discover the references to the Book of Job (the epigram, of course), but where the ghosty dimension -with the Victorian mansion and the MacNultys- come from? Is there a Henry Jamesian direction there?

I am one of those suspect readers of James who only truly likes The Turn of the Screw. The effective atmosphere of terror and mystery in that house. But equally important would be that other James, M.R. James the ghost story writer, a great favourite of my mother’s. Miss McNulty is obviously a topsy-turvy and innacurate portrait of my mother in the 60s, and I would be that little boy in the Turret Flat. My other crazy influence would be Einstein’s Theory of Tme — all things happening everywhere at the same moment eternally. Which was so useful to me, because all Tom wants is to get back to the 60s (he’s an aging man in the 1990s) and how could I get him there, and as a consquence back to his beloved wife June, without Einstein? Bergson said Einstein’s theory is pointless as it has no pracctical value, but clearly I disagree.

Although there are a lot of small “tragedies” registered in the novel, the tone is rather tragi-comic. Do you feel more at ease when depicting both black and white in life?

Well, humour is the salt and recompense of life. St Peter might like a joke at the famous gates. A funny remark might get you into heaven. There has never been an Irish person so tragic that they don’t have recourse to humour, for instance the Irish soldiers in the trenches in WW1, who were famous for their indefatigable wit, though they might be up to their waists in rats and mud.

“The fog edged away from the shore of himself, the sea opened like the stage in a theatre…”. And somewhere else Tom thinks that his life was like a play, a scene where he must utter certain lines. It seems that theatrical effect is important in the novel, isn’t it?

That’s an interesting question. I suppose it is a Shakespearian idea, but Miss McNulty is an actress and I myself spent a huge amount of time in the theatre with my plays. Modern novels often have a two act structure like a screenplay or a play. Moreover the very vista from his room, that he loves so much, actually looks down on a little concrete jetty where my heroic sister and I used to improvise tiny ‘plays’ when we were children.

Apart from the plot itself this is a book about not to trust the narrative voice, because sometimes it fades between reality and dream. How did you cope personally trying to find the best ways while narrating and at the same time avoiding ornamental style?

With great care. In the end I thought it was best to explain nothing, and just attend to the camera and imagination and responses of Tom. So that if something seemed true to him, it was in that sense true, if provably not. It was quite an exciting thing to do, if a bit wicked, since we do put our trust in novels, there is a pact between reader and writer. But that wasn’t really available to me here. It can make the writer feel a little mad!

Is there most of the time a tune/ rhythm behind the lines you write? Do you have to listen to the sentences’ music?

I always try and find first the birdsong, the whistletune of a particular book. It can take years, strangely enough. Once you have it, you’re away. If you can find the first sentence, with its proper music, the rest of the book should be lying there behind it, were you to tilt that sentence.

Did you ever feel so much stressed when you had to deal with traumatic memories, forced to think about them?

Not so much writing the book, because essentially it is a very exciting and mysterious undertaking, and nothing you write in that mood seems either benign or threatening, but simply there. I was very devoted to being as clear as possible, if not in respect of Tom’s memory, then at least in the details of his suffering, and June’s suffering – but also their great happiness, of course. After all, Tom is a detective and in his later career forensics were just coming into play. But later, in the year I spent going around the UK and Ireland, talking about the book, I sometimes felt slighty overwhelmed. There’s a difference between the writer and the person. In Cambridge, for instance, my friend Ali Smith gave me a little tiger pin for the lapel of my jacket jacket, and said it would protect me. A lovely thing to do, of course, but she is angelic.

Does the amount of exciting fiction coming out in Ireland means that there are also a lot of readers in your country?

It’s one of the miracles of the modern age. Readers can seem much cleverer, more adroit, more penetrating than writers, which is a good thing. They bring their own lives to the table.

Which are some modern Irish voices that you like to observe and have an eye on them?

Claire Louise Bennet is pretty much a genius. There are so many. Colm Toibin and I are the same age and are true friends so I always look out for what he’s doing. Roddy Doyle also, but truly, there is a myriad of world class Irish writers, and it’s very handy for me at 68 to be able quietly to steal from them, if I can get away with it. That’s what Seamus Heaney used to ask me when I had a play opening – ‘Did you get away with it?’ Like the writer is a sort of Jesse James figure, which I suppose he or she is.

Do you feel there is a threat for literature when people demand certain titles to be “adjusted” or rewritten in a way?

It is a grave unkindness and a huge mistake. You have to trust the writer to exercise their own sense of responsibility, even if they get it wrong. Fiction is the art of getting everything wrong, to reach an otherwise unreachable truth, if that doesn’t sound too grand.

Do you have books that keep “reading” after you closed the actual book?

I read Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo last in the seventies, but it hasn’t ended, and likely never will.