Glance at the menu in a traditional Greek seafood taverna, and it instantly becomes clear that customers pay a premium for fresh local wild-caught fish. But have you ever wondered if the delicious meal you paid so much for really was sourced locally and cooked fresh? And how “sustainable” is it? Maybe it arrived there via a fish farm and freezer, or was fished from a protected or polluted area. Being able to identify where fish and seafood is caught and harvested, along with every step they take along the supply chain, is known as traceability. Since an increasing number of policymakers agree that “traceability” is the key to sustainable fisheries, there has been a push to invest more money in the relevant technologies.

The enormity of the challenge involved in tracing every fish that’s caught and tracking it all the way to your plate is clear from the sheer size of the global fishing industry. The Food and Aquaculture Organization’s (FAO) newly released report shows that global fisheries and aquaculture production reached a height of 218 million tonnes in 2021, and is expected to keep growing.

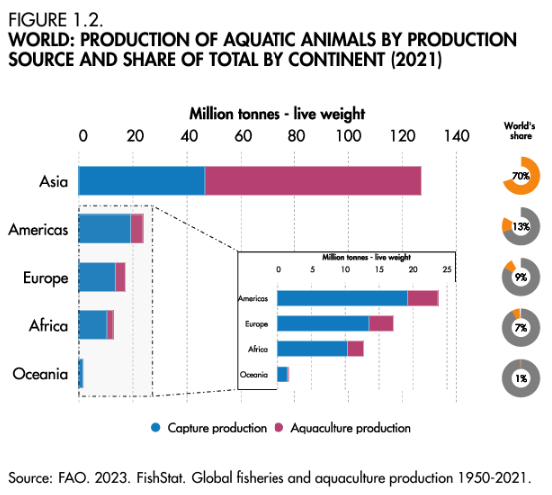

The increase in numbers are “largely due to the growth of aquaculture in Asia and of capture fisheries in the Americas.” Taking a look at what this means in terms of production per region, “Asia accounted for 70% of the world production of aquatic animals, followed by the Americas (13%), Europe (9%), Africa (7%) and Oceania(1%),” according to FAO.

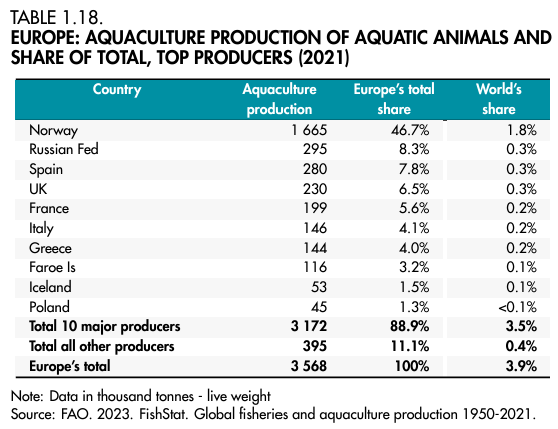

To get a sense of scale when looking at the Greek production figures, even though Greece is listed in the top 10 aquaculture producers in Europe, its aquaculture production is a mere 144 thousand tonnes per year against China’s 51,221 thousand tonnes.

But there are other challenges when it comes to promoting traceability, beyond the size and global distribution of fisheries. Some developing economies and small island developing states (SIDS) are highly dependent on fisheries and meeting the tremendous growth in demand is putting them under considerable pressure. This makes them resistant to additional regulation and the tracking and reporting that traceability would require.

Of course, this flies in the face of stark warnings about the threat of fishing stock collapse and the further impact of climate change on the sector from, among others, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN recently said that “25% (3,086 out of 14,898 assessed species) of the world’s freshwater fish species are at risk of extinction.”

And traceability is crucial for accountability, transparency and sustainability. It plays a pivotal role in safeguarding marine ecosystems, ensuring responsible fishing practices, safeguarding food safety and quality, combating illegal fishing, supporting fair market access for producers, and empowering consumers to make informed choices.

Investors seem to have taken notice. According to an announcement from the WWF, 34 investors representing US $5.9 trillion recently joined the “Seafood Traceability Engagement”, an initiative launched by the FAIRR Coller Initiative in 2023 in collaboration with the WWF, UNEP FI, the World Benchmarking Alliance, and Planet Tracker.

The idea of promoting traceability is not a new concept, however. In fact, it underpins the many sustainable fisheries food labels, such as the “dolphin safe” logo used on cans of tuna since the 1990s. Unfortunately, a series of recent documentaries have revealed that some of the best-known “certifications” lack transparency, inspections, robust data and enforcement, making the need for traceability more crucial still.

Greece’s fishing sector has been making strides in traceability through its Integrated Fishing Activity Monitoring System (OSPA), which aims to promote “the sustainability of marine living resources in fisheries and aquaculture in the new digital age.”

According to the Greek Ministry of Agriculture and Food, the OSPA system is a digital application that fishermen activate when they leave port and have on throughout their time at sea. The app sends real-time data to a central database that can track where the fishermen went and what they caught. This allows the Greek regulatory authorities to monitor their activities, but is also helps the fishermen prove the legitimacy of their catch.

Commenting on the application, a local fisherman told To Vima, “I didn’t want to install the application at first, because I’m not good with technology. But I was getting hassled by the Coastguard, and it wasn’t always easy to prove I’d caught my fish legally. There are so many rules and restrictions. Anyway, I finally installed the application, and at least it’s got easier to declare my catch. Now, if only the application could bring back the fish…”

OSPA is now entering its second phase, according to a recent Ministry announcement, and the system is to be extended to include buyers and sellers of fish. But while it’s good that key steps in the supply chain will soon be covered, much more work will need to be done to develop sustainable fisheries.

We still need to integrate ecosystem-based approaches that respect the environment and must educate, engage and collaborate with local communities and all stakeholders. We also require data-informed policy reform, international cooperation, and further innovation in fishing techniques and aquaculture. And, of course, we need to prepare for the multidimensional and destabilizing impacts of climate change on our fisheries.

This article is part of a special thematic series covering key issues related to the 9th Our Ocean Conference, which will be hosted by Greece this year. The event will be staged in Athens on April 15–17 at the Stavros Niarchos Center.